Sancintya Mohini Simpson is a descendant of indentured labourers sent from India to work on colonial sugar plantations in South Africa—and her art is entwined with this history. With work spanning multiple forms from painting to performance, Simpson speaks about her familial history, accessibility in art, and the nature of collaboration—and what she’s exhibiting for her solo show at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA).

Your first art love?

Growing up, we didn’t go to many places outside of the usual, but we did go to art galleries, libraries, and parks—as they were free and accessible. So, my first art love was the art gallery itself, and the free activities and workshops for children they provided. Access has a big impact, and I’m grateful for these spaces in providing that.

Best time of day to create?

I try to mostly work usual day hours, but I find my most productive times are when it’s quiet and everyone is sleeping. The stillness allows for interrupted space to think, work and focus.

You work between painting, video, poetry, and performance—did you think you’d have a multidisciplinary practice, or did that evolve instinctually?

It’s funny, as my father was recently telling me about how he had never expected me to become an artist and had thought I’d do something like study law—but he had just realised how obvious it was that I would be an artist, and that he played a large role in this.

I was always making things and reading. I did it all as a child and teenager: painting, writing poetry, performing. I was just unaware of the importance of it in my life, because in my mind I wanted to change things and say things, and I didn’t know I could do it through art at the time. I also was very privileged to grow up in a house of creative people, who just did it—but not for others or a job, just because they needed to create. This had a natural sway.

As an adult, I felt like I had to relearn that instinct to just make what I needed to, and navigate what I needed to communicate, even if it was learning new skills and asking for help to do these different things. And it’s also partially going back to that desire to make without structure and without someone telling you what to do, and the space that comes with that freedom.

Being a descendant of indentured labourers informs so much of your work. Was this entwined with your practice from the beginning, or did it take time to make work about this history?

My practice early on had been a way to make sense, understand and process things, so naturally what I’m navigating in my personal life is reflected in my practice. It was through my mother that the pieces came together.

As I was trying to make sense of the experiences and lives of the women in my maternal line, and myself, my mother was trying to apply for an Overseas Citizenship of India document. As she needed to show proof of her Indian ancestry, we received a list of details of our ancestors taken as indentured labourers from Madras to Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). The list we received was taken from a ship list using numbers listed on my uncle’s birth certificate. It was through this list that the pieces came together, and I realised that I needed to address and understand this history, and the ongoing impacts of intergenerational trauma and acknowledgement of the women whose histories weren’t visible.

“Collaboration is a pure joy when it works, and you can deeply connect with another person to create something together through mutual exchange and generosity.”

After this, in 2012 you travelled to South India with your mother, Indarami, whose ancestors were taken from India by the British Empire in the 19th century to work on sugarcane fields. It seems like that trip had a huge influence on you and your art. Can you reflect on that, especially now a decade later?

I had just finished my undergraduate degree and was navigating my relationship to maternal cultural inheritance and had convinced my mother to spend an additional week of her usual trip to India visiting some of the villages our ancestors had come from—based on what was listed on the ship lists—and let me photograph her.

I then went back to India in 2013 and spent a month learning Indian Miniature painting from artist Ajay Sharma in Jaipur, Rajasthan, and I then used this technique to paint on the photographs of the trip with my mother. At that point I hadn’t put any of these pieces together, in understanding what questions and answers I was looking for—and it was only in 2016 that I realised that I was trying to understand where the intergenerational trauma had come from and make sense of that history, and my and my mother’s relationship to it. Then in 2017 I started making work to acknowledge that history in a direct way.

You’ve since created pieces that involve collaboration, but if you could collaborate with any artist who would it be?

Collaboration is a pure joy when it works, and you can deeply connect with another person to create something together through mutual exchange and generosity. My list of living artists that I’ve made plans with is long enough. I personally feel that to collaborate with someone there needs to be a chemistry, an understanding, respect, and bond—and without knowing if that is there first, I personally don’t feel collaboration is right.

I will say that my favourite artist to collaborate with is my brother, Isha Ram Das, who is an experimental sound artist and composer. I feel there is a real joy in collaborating from the natural understanding we have. Our natural languages of visual and sound support each other, especially through the sound and visual vocabulary we share from growing up together. We have been collaborating since we each began our practice and, in a sense, have been navigating collaboration since we were children playing together.

I know you’re a relatively young artist yourself, but what advice do you have for young artists?

Being an artist can be quite isolating and difficult to navigate alone, so your art community is so important—and the best part of being an artist. It took me a while to find artists who fill this space for me, and I am so grateful for how generous they are with their knowledge and time. People who you can share knowledge with, and mutually support, are vital in keeping yourself and your art true, real, and honest— and yourself sane.

“For me this exhibition at PICA, ām / ammā / mā maram, feels the most personal. It’s almost a full circle thematically from 10 years ago when I was making that work with my mother in South India, except I have a fuller understanding of the story and my relationship with it now.”

An art experience that’s stuck with you?

I was recently able to see new works exhibited by my dear friend and colleague D Harding—and I’d seen these paintings at the studio, but it was an entirely different experience seeing them hung and in conversation in the gallery.

I had been travelling for work and had seen a Rothko painting for the first time the day before and didn’t really respond to it, but D’s paintings made me feel a lot. The presence and spirituality of the work and materials, with D’s energy and body present in the strokes evoked a lot of emotions for me. It was so beautiful to see ochres from D’s grandmother’s and grandfather’s Country side-by-side in one work (She come from the low-country, he come from the high-country, 2023) and D’s use of PrEP tablets as pigments against lapis lazuli in another painting (I have learned your history, as well as my own, 2023).

For your solo show at PICA, can you talk through what you’ll be exhibiting?

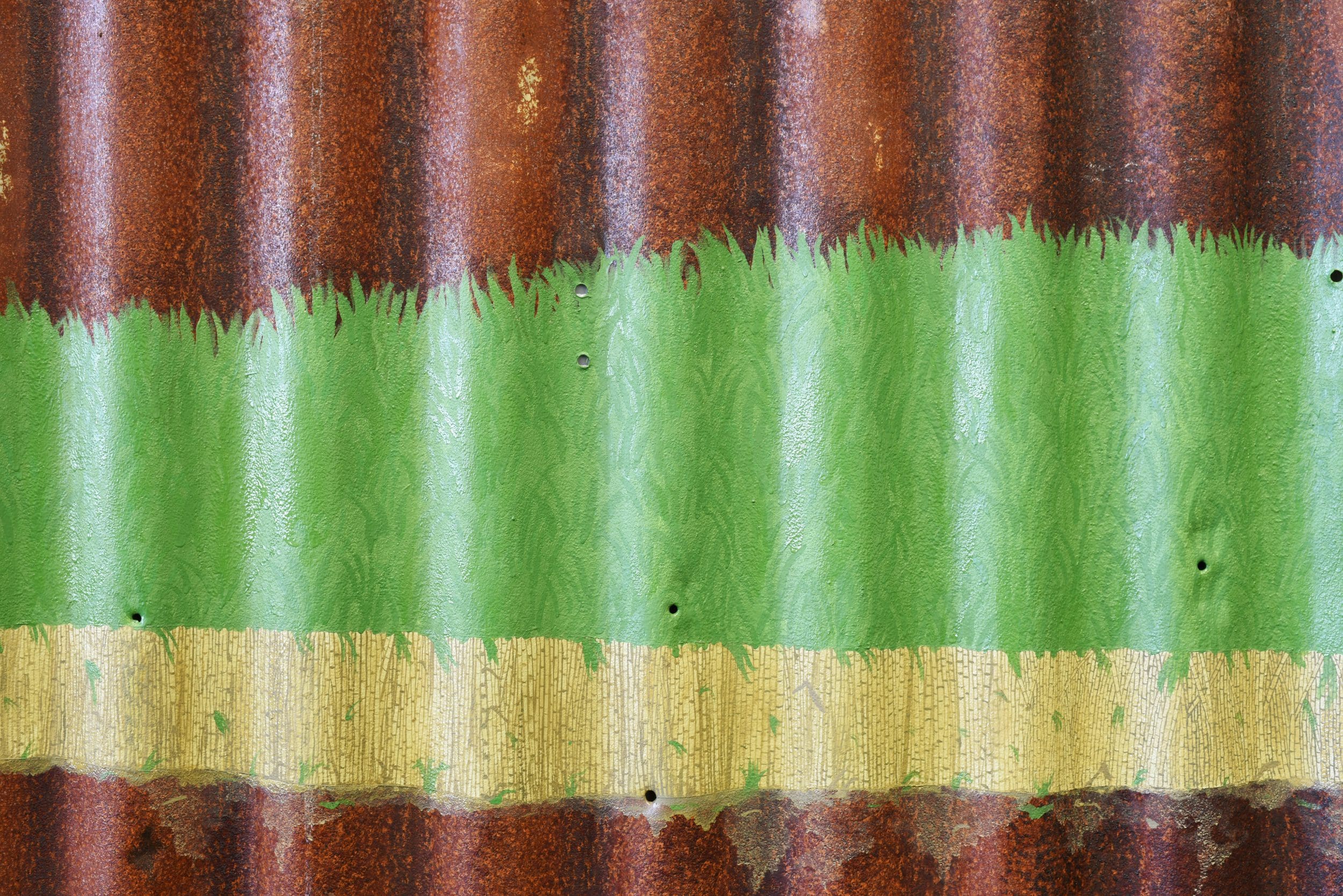

For me this exhibition at PICA, ām / ammā / mā maram, feels the most personal. It’s almost a full circle thematically from 10 years ago when I was making that work with my mother in South India, except I have a fuller understanding of the story and my relationship with it now.

I feel a lot of threads have come together, and this exhibition acknowledges histories, time and inheritance through materiality, place, and embodied memory. The works are all in conversation and are quieter. I feel they are saying more with their materials, and how they come together, rather than a direct or didactic depiction. There’s a photograph of the women in my family and female neighbours, in what seems to be only a few years before my mother was born, including her mother, aunt, paternal grandmother and maternal great-grandmother. There’s also handmade paper from the mango trees in my mother’s garden, black clay vessels fired in sugarcane ash, burnt mango wood, corrugated iron paintings, poetry and scent.

I’m looking forward to sharing this work in this space—as Perth has a closer proximity to South Africa, I feel it is more apt.

ām / ammā / mā maram

Sancintya Mohini Simpson

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (Perth WA)

4 August—22 October

This article was originally published in the July/August 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.