Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

A bunch of grapes recalling surrealism and strange mirrors. A bronze twig spelling out words of ‘cope’, over and over. The ants are in the idiom, the largest solo show to date by Sydney-born, London-based artist Susan Jacobs rewards a curious eye. There’s a reverence in the way curator Jacqueline Doughty speaks of Jacobs: “she’s been quite influential for a new generation of artists,” she says.

Developed over three years and sprawled, maze-like, across Buxton Contemporary’s three gallery spaces, this playful and absurd series of works forges connections and blurs lines between nature and art, words and matter, real and imagined.

The first room is spatially wide in its blankness, save for 101 identically shaped glinting gypsum tablets: silver, bronze and gold. A careful observer will notice that they mirror the windows opposite. These objects were cast from a discarded rear-view mirror, found on the ground during Jacobs’s walks in London; she thought she saw the Virgin Mary in its reflection, but it was just a trick of the light.

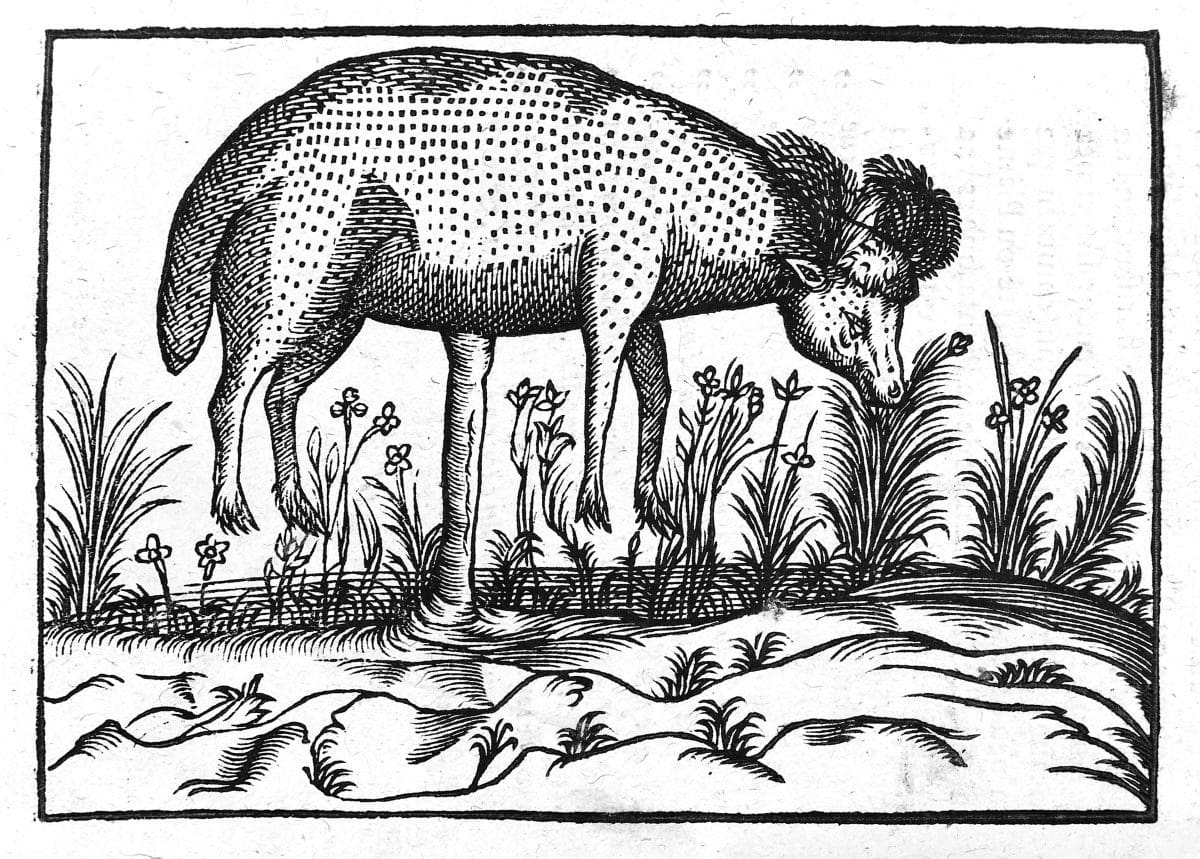

Next, a plunge into darkness, illuminated only by three lights positioned over clay bricks on a table. The scent of basil oil is thick in the air; occasionally, a machine shudders and hisses. It’s like being in a laboratory; Doughty describes it as having “a touch of magic and alchemy”. This work, A Recipe for Scorpions, recreates Belgian physician Jan Baptiste Van Helmont’s method for generating new life from decaying matter as per the theory of spontaneous generation, as does A Recipe for Mice in the next room, where mouse excrement is fashioned from clay, like a scene from a natural history museum.

Jacobs’s interest in spontaneous generation was born through her readings at the Wellcome Collection in London. Jacobs sees a reflection of art in this theory. “These ideas about life emerging without a parent or a seed from inanimate stuff were around since ancient Greek times up until 1859—it’s such a wonderfully long mistake,” she says. “Making things can sometimes be trial and error—there’s a similarity in that way, and this sort of questioning that’s pretty open.”

These works are in conversation with the installation Pasteur’s Grapes Inverted as the Lovers in the final gallery. In this work Jacobs recreates French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur’s experiment for fermentation, where one bunch of grapes is wrapped in cotton wool and the other stands bare. Here, Jacobs sees another mirror between science and art as the work, presented under a dome, resembles René Magritte’s famous paintings. It’s a suggestion of romance in a clinical space stripped of it.

Jacobs looks to the space between science and art, prying out the possibilities. “For me, it’s about wonder and not knowing, and the undoing of trying to solve something,” she says. “What actually comes from the fallout in the art process is more interesting . . . The thought process isn’t literal.”

Winding round the corner from the compressed second gallery, I’m spat out into a wide open space, busy with material. The eye wanders frantically. This last gallery is almost industrial, with two fake grey pillars indistinguishable from Buxton’s permanent fixtures. There’s no obvious path through the artworks—it feels like a street market, Doughty notes. Most of these works form Market Fray, which harness this rhizomatic setup, playing alongside the idea of garden-path sentences, leading a reader down one path, then changing in the middle, creating a sense of distortion.

“What I’m aiming for is the sense that I’ve had going through an environment and having something grab me out of the corner of my eye,” Jacobs says. “Something that’s come up through doing the work is thinking about a kind of sculptural syntax, in the way that a sentence might be formed to lead a particular group of things or words to project a kind of meaning . . . Things feel like they coalesce to articulate themselves.”

Tables containing objects are scattered around the room; wires overhead seem like scaffolding, but upon closer inspection are a part of the show; glass jars resemble animal bodies, and clay offcuts look like claws. A plastic bag is stretched and cut to replicate an animal hide. An apple core is remade in gold. Detritus becomes precious.

And then, the magic in the ordinary: carved in bronze, a recreation of a twig Jacobs saw on a walk that seemed to spell the word ‘cope’ repeatedly until it appears meaningless. Was it ever there at all? “I’m interested in what happens in that process when we clock things and we want to make meaning out of them so we can understand our environment,” Jacobs says. This phenomenon—pareidolia—perhaps became more prominent than ever during a time of great global disruption.

In this space, sound bleeds from the elevator: bird cries from Mikala Dwyer’s work Ode to the ‘ō’ō, part of the Buxton Contemporary’s sister exhibition, Still Life, upstairs, while a scrawl sprawls across the last wall, tracing the etymology of the word ‘answer’. It’s a strangely beautiful and apt chiming of worlds, illustrating the coalescence Jacobs mentions.

I leave in a daze, mind swimming. If art is in life, and life is in art, then we are everything we see.

The ants are in the idiom

Susan Jacobs

Buxton Contemporary

(Melbourne VIC)

3 June—6 November