In bygone centuries, when a ship sailed into a new port the first person to step aboard was called the ‘tide waiter’. It’s a job title as laden with symbolism as the cargo-heavy ships they once inspected; as they checked the merchandise, reviewed the paperwork, and counted the money, the tide waiter was a one-man interface between isolated colonial outposts and the criss-crossing shipping routes that made an age of empire tick.

For artist Sue Kneebone, finding such a man in her family tree brought complicated tidings. Over the past two decades her visual arts practice has threaded together found materials and archival information to interrogate and reflect upon the impact of settler colonialism on the landscape of South Australia.

“I’ve used family history to sort of piece the dots together, to understand the bigger historical events of post-colonialism and empire,” Kneebone says. “It takes me on a route into that broader history, that bigger narrative.”

Kneebone’s great-grandfather arrived in the colony in 1879, after supposedly jumping ship from Mauritius. But it was his father—a mysterious figure named Christopher Kneebone who worked as a tide waiter in Port Louis in the 1870s—that allowed Sue to embark on an even bigger voyage.

“The rumour was he had [been] brought up by guardians in Mauritius, so no one really knew how he got there, who they were, or if he really was an orphan.”

Kneebone followed the trail to archives in middle England, India, and eventually to Mauritius, where she found a local cemetery dotted with headstones that shared her surname. The graves commemorated three generations of Kneebone, and a lineage entwined with the British Empire’s history of trade, militarism and conquest.

As a stop-over on the route to India, Mauritius was of keen strategic importance to imperial Britain; it was this military industrial complex that led Christopher’s birth father to Mauritius, and later British India, working as a quartermaster responsible for military supplies including food, uniforms, weapons and even musical instruments.

“Going to Mauritius was a huge shift in my perspective and understanding of Mauritius as a strange, strategic little island formation of the British Empire,” she says. “So I’m kind of looking at the microcosm, and the macrocosm.”

In August, Kneebone presents a new exhibition as the featured artist of the South Australian Living Artists (SALA) Festival, titled The Last Tide Waiter in a nod to her great-great-grandfather and the “trans-oceanic” legacies braided into his story.

One of over 700 exhibitions and events presented as part of the statewide festival, The Last Tide Waiter presents an ‘accumulation’ of material collected during Kneebone’s years of research, drawing links between the historical narratives of the 19th century and the environmental degradation that centuries of exploitation and disruption has left behind.

“I’ve got a vision of this space being a bit of a customs warehouse that’s gone awry;” she says.

Kneebone’s work has often betrayed a knack for the gothic and uncanny; 2010’s Unnatural causes still haunts the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Elder Wing with its headless figure dressed in coattails stuffed scarecrow-like with emu feathers and horsehair.

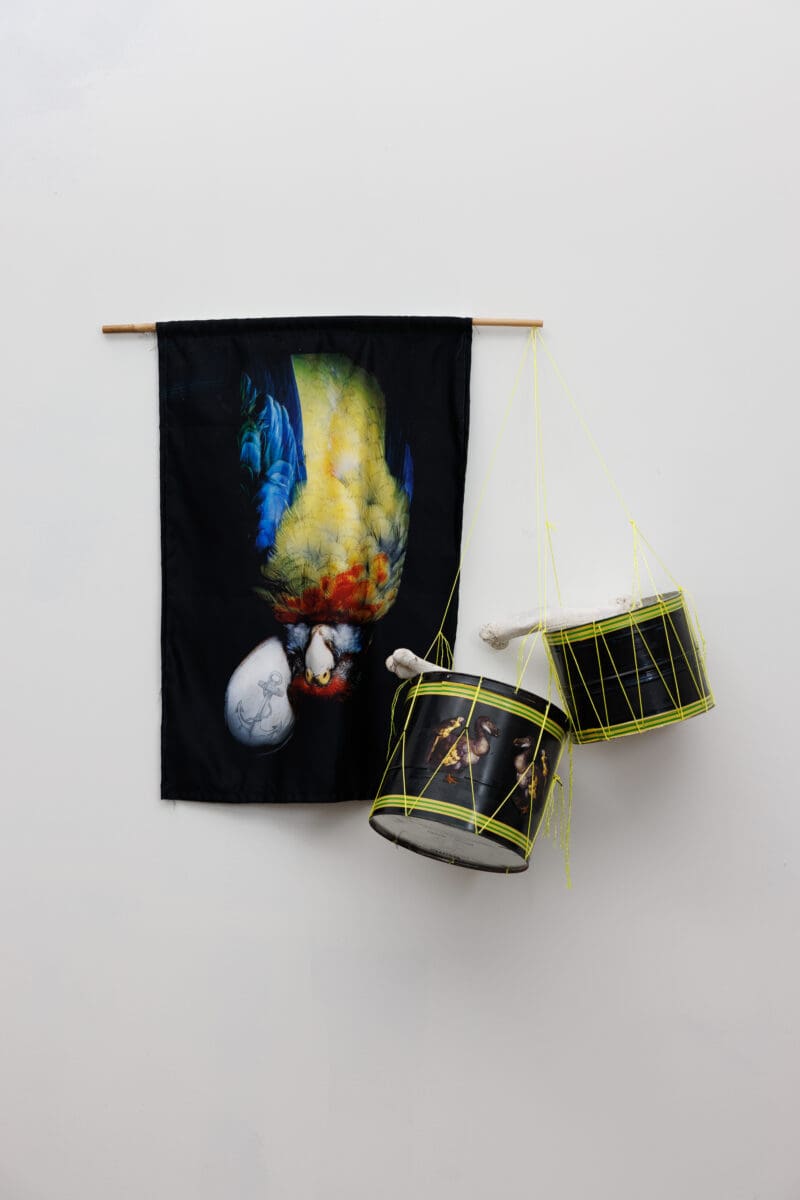

The Last Tide Waiter is no exception, with Kneebone’s warehouse including rope-bound drums, cymbals and knotted horns that nod to the soundtrack of empire that once marched through colonised territories.

“There is also a sound element to go with it, made from sound grabs I recorded of a Hindi street procession with musicians playing drums, cymbals and horns outside of where I was staying in historic Fort Kochi, Kerala,” she says. “I’ve slowed it down and layered it a bit, so it sounds like a bit of a cacophony.”

The exhibition also includes a physical reminder of her family’s seafaring history: an old desk that belonged to her late father, who passed away last year. “I just cleaned up his place and ended up with a desk, which I think has come from the Channel Islands, from his side of the family. It’s an heirloom that’s come across the oceans.”

Like her ancestor, we’re invited to inspect these wares—and count the cost.

“It’s [a] kind of…procession around the room of artefacts which will almost turn into a procession of ecological grief,” she reflects. “The past has caught up with us.”

The Last Tide Waiter

Sue Kneebone

Adelaide Central Gallery

5 August—5 September