Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

How do you document an artist’s practice? The traditional monograph is often about tracing the development of an established artist’s work over time. It identifies connections and through-lines, and suggests ways to consider critical significance. But it can also be about much more. The creative choices around how a monograph is put together can also speak powerfully about an artist’s values and the questions that drive their practice.

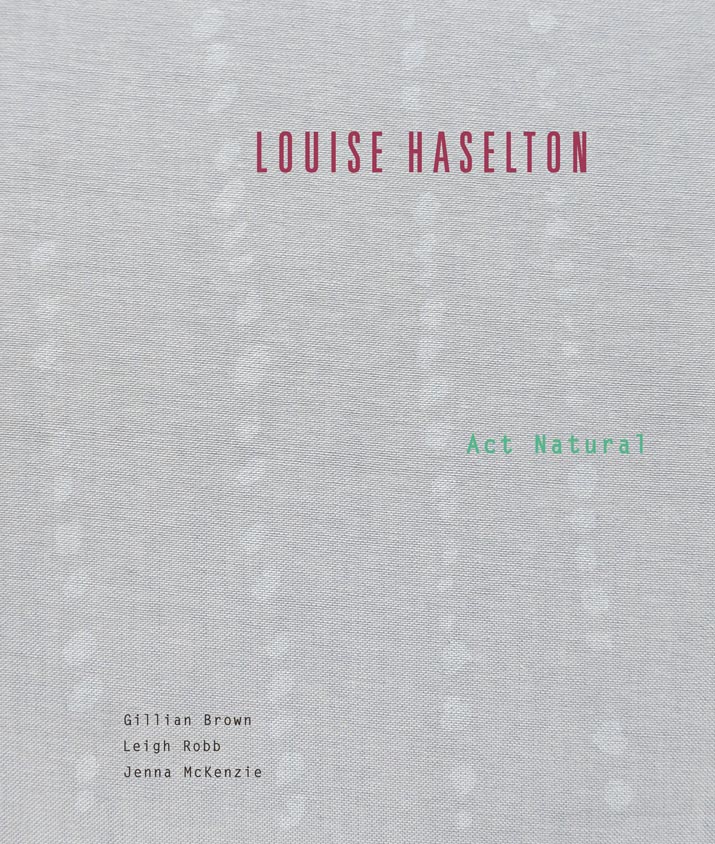

The long-running SALA monograph scheme has now published 25 books on established South Australian artists, including Helen Fuller, Roy Ananda, Michelle Nikou, Kirsten Coehlo and Nicholas Folland. The scheme operates with the knowledge that artists outside the major centres don’t always get the attention they deserve, and that’s also true for Louise Haselton, the subject of the SALA monograph in 2019. Act Natural covers 30 years of her practice and often feels like the major institutional survey her work should have received by now.

Haselton works with everyday materials, and has a knack for setting them together into strange, sculptural combinations. A door handle is wound with yarn. Objects are covered in tiny round mirrors so that the closer the viewer gets, the more of themselves they see. Act Natural moves through key chapters in her practice, and explores the development of her visual language, but one of the best things about the SALA monographs is the space it provides for new scholarship. In one essay, Samstag curator Gillian Brown writes lyrically about approaching Haselton’s works like mysterious standing stones, treating them like compelling objects with hidden histories. Jenna McKenzie compiles an engaging and very personal biographical timeline. The Art Gallery of South Australia curator Leigh Robb also takes up Haselton’s early work, framing her as an artist who has always been in some way “wrestling with the creative act and the space between its idea and its form.”

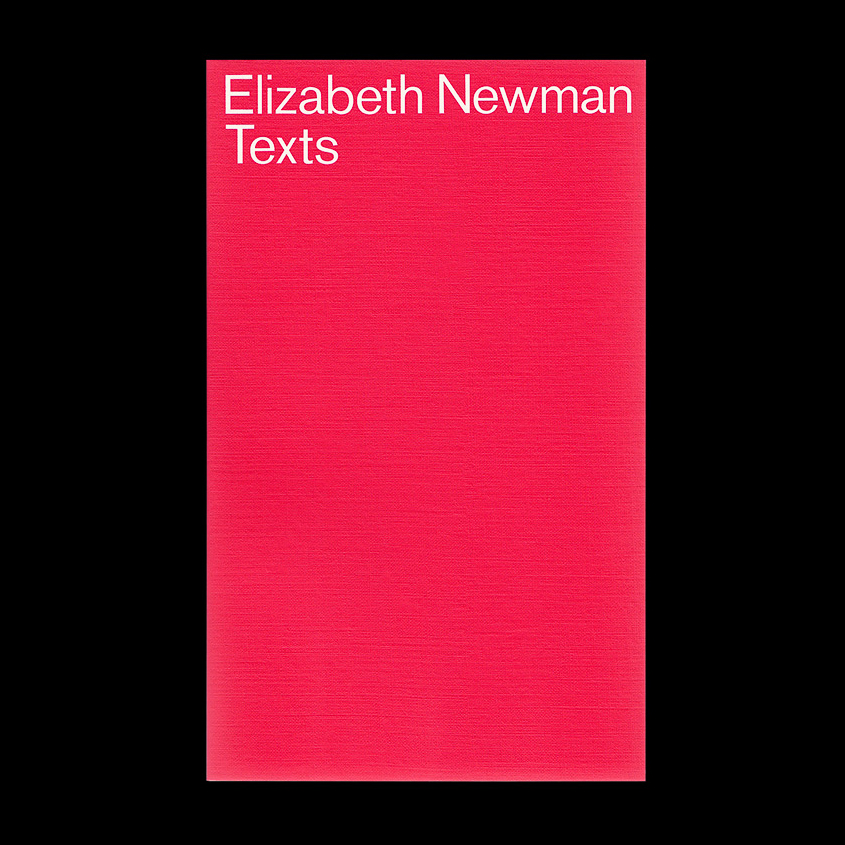

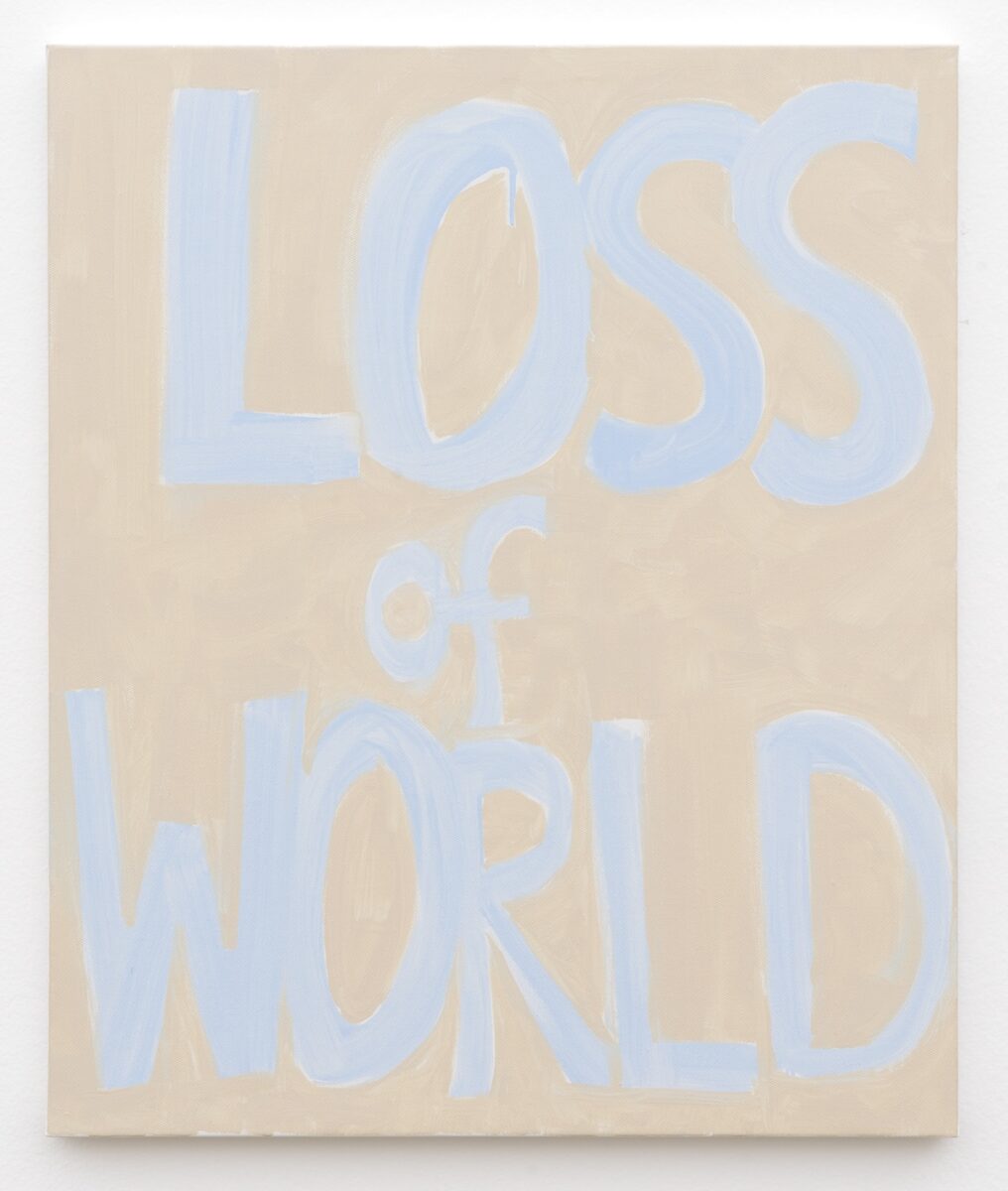

It’s a space also explored by Elizabeth Newman in Texts. This softcover chapbook was brought out by Discipline in 2019, and is now one of several volumes on the artist. Newman is known for her abstract, minimalist approach to painting but writing has always figured in her practice. An early untitled text work from 1989 proposed: “The AUTHORITY of Art rests upon an invisible platform of knowledge and power.” Texts picks up a little later, with notes and essays from 2005 to 2019, but shows an ongoing fascination with the dynamics of creative and communicative acts.

Newman also has a background as a psychoanalyst. She ranges over many topics in Texts, but returns often to the gap between the knowable and unknowable, and between representation and the real. She’s at her best when she’s defending this precarious territory. In one piece, she mounts the case for untitled artworks. In another, she rails against politicians who claim to ‘say what they mean’. “Australians are famous for this superficial simplicity…It’s a way of evacuating ideas and content, and therefore difference, from our speech,” she writes.

Texts is really a companion exploration to many of the same questions that drive her painting practice. Some of these pieces were written for publication, but they always retain a notebook-like quality, as if Newman is most interested in working things out for herself than convincing a reader. That means Texts can sometimes be a whistle-stop tour. She doesn’t always give herself time to ground her experiences and arguments before leaping into theory.

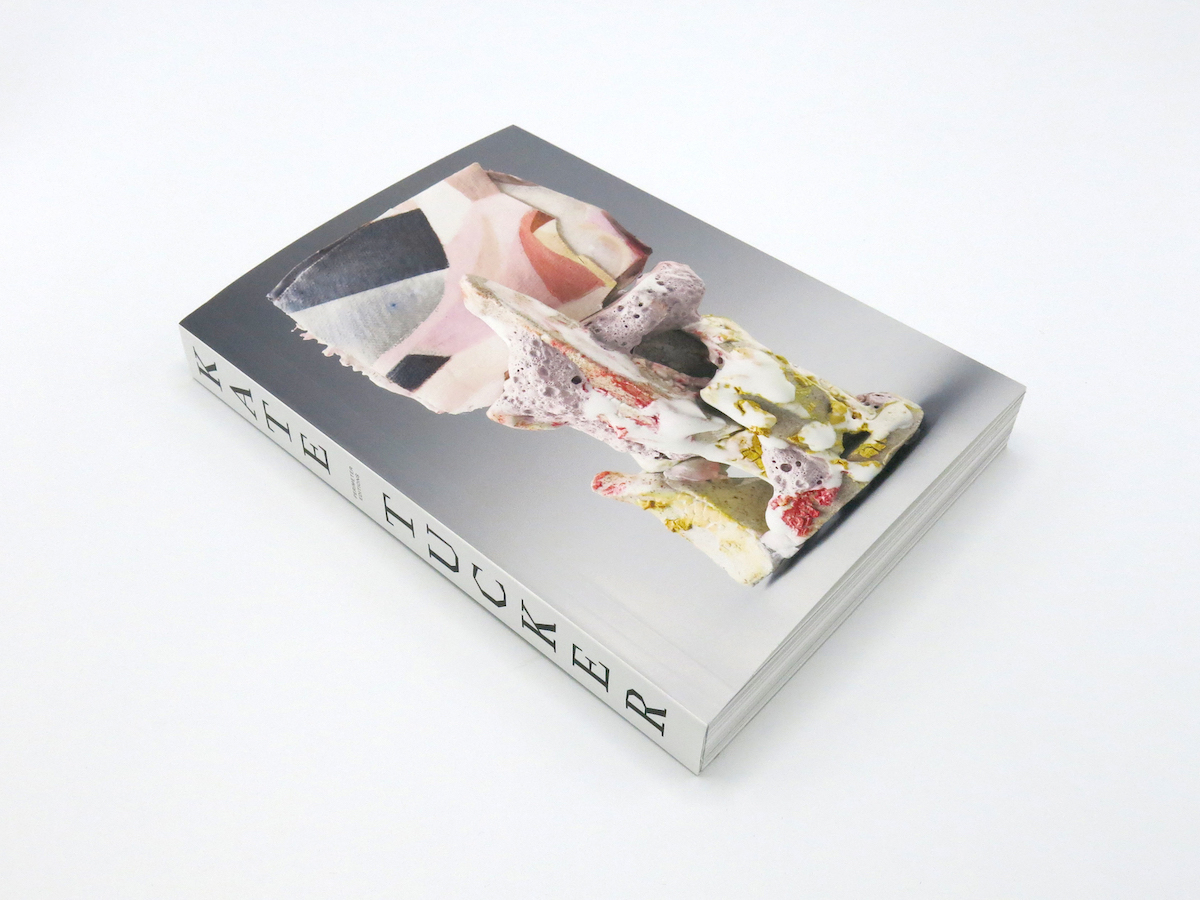

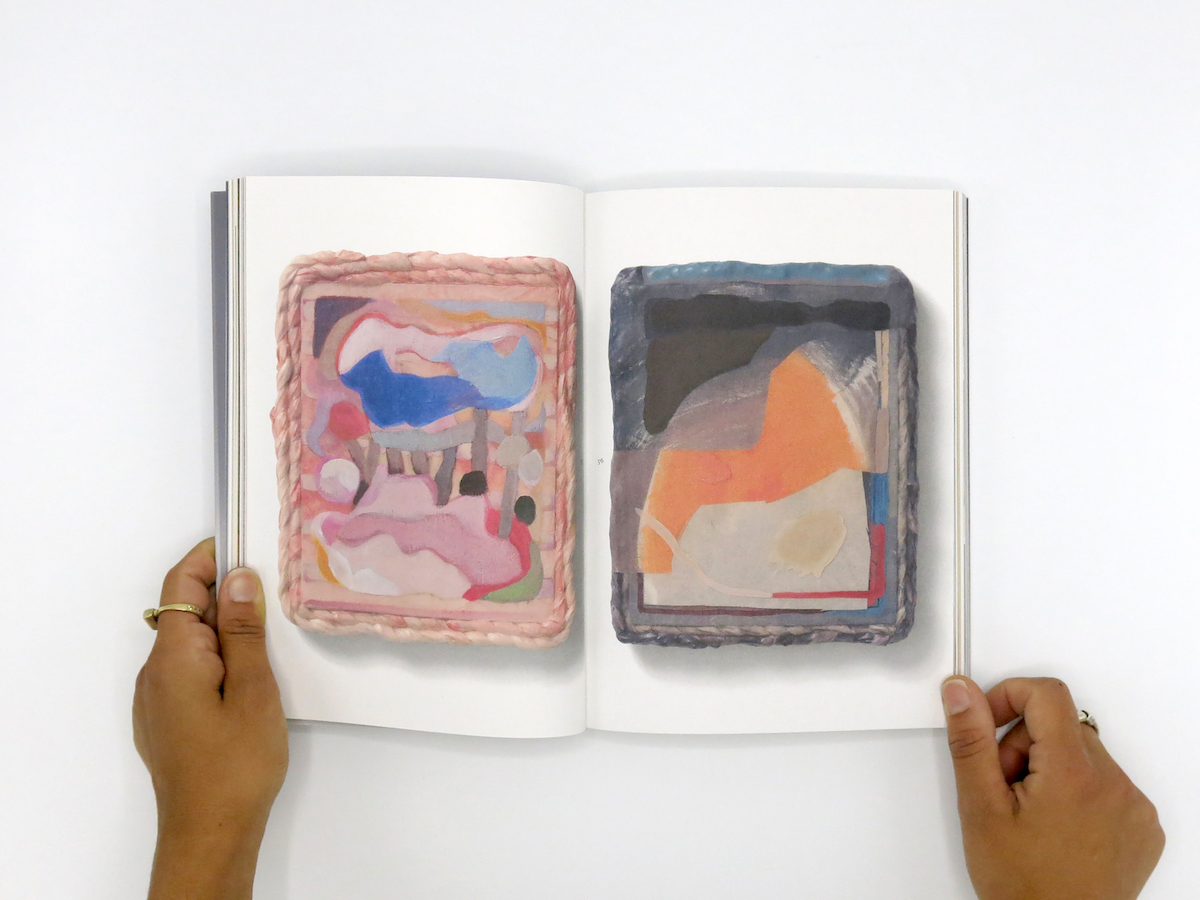

Identities can also be hard to pin down in Kate Tucker’s new monograph, A Community of Parts. It documents her work over 2015 to 2023, and tracks Tucker’s movement away from abstract painting towards something more akin to sculpture. Frames and plinths become built into the works; the line between the main act and support is blurred. “You can’t really perceive the parts,” she says in an interview here, “because they’re forced together into one.”

A Community of Parts seems to be trying something similar. There is no artist CV, the usual method of telegraphing cultural capital and value. The 249 images are arranged chronologically but the huge volume shifts the focus from key works to the iterative nature of Tucker’s practice, and the value she places on rhythm and momentum. A Community of Parts is ambitious and beautifully put together, although the title ultimately sets up a promise that is never fully realised. The texts make light connections to feminist practices, drawing on the anthology The Mother Reader (2001) and also Miriam Shapiro and Melissa Meyer’s concept of ‘femmage’, a term coined in the 1970s for activities that were traditionally considered women’s work. There is also a brief mention of Céline Condorelli’s book Support Structures (2009) but beyond that, the broader intellectual and creative communities around Tucker are left largely unexplored. And that will always be the challenge of documenting any artist’s practice; finding the way to show their place in the world, the lineages they are drawing on, and what they might be building for others in turn.