Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran is known for his iconoclastic figurative sculptures that are bright, bold and larger than life—no matter what their actual size. As an artist he moves fluidly between hand-built ceramics and large public sculptures, figuratively and politically looking into idolatry, race and gender, always with an irreverent exuberance.

In 1989, at the age of just one, Nithiyendran immigrated to Australia. In 2017, already trailing a string of awards, he became the youngest artist to present a commissioned solo show at the National Gallery of Australia.

In March 2021, after two productive years at the Parramatta Artists’ Studios (PAS) complex at Rydalmere, Nithiyendran moved into new premises in an industrial park in Gladesville, on Sydney’s lower north shore, with fellow PAS alumnus Yasmin Smith. Here, he talks about his early peripatetic studio “promiscuity”, and that he glazes like a painter, but still gets a thrill out of opening the kiln door.

PLACE

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: I remember when I was starting out, I was a little bit promiscuous in terms of my studio environment. You know, I’d sometimes work in my parents’ garage, then I’d work at Kil.n.it [a not-for-profit ceramics space] where I had a studio, or I’d see if UNSW, where I studied, would let me work there in the holidays. I think all artists have that hustle in the beginning.

And, on a very literal level, it affected my sculpture. A lot of the time the works were really frontal; I had to make things on tables against walls because I wasn’t working in a space where I could walk around them. But ever since Rydalmere, and this space, I’ve been able to be more ambitious with the sculptural language.

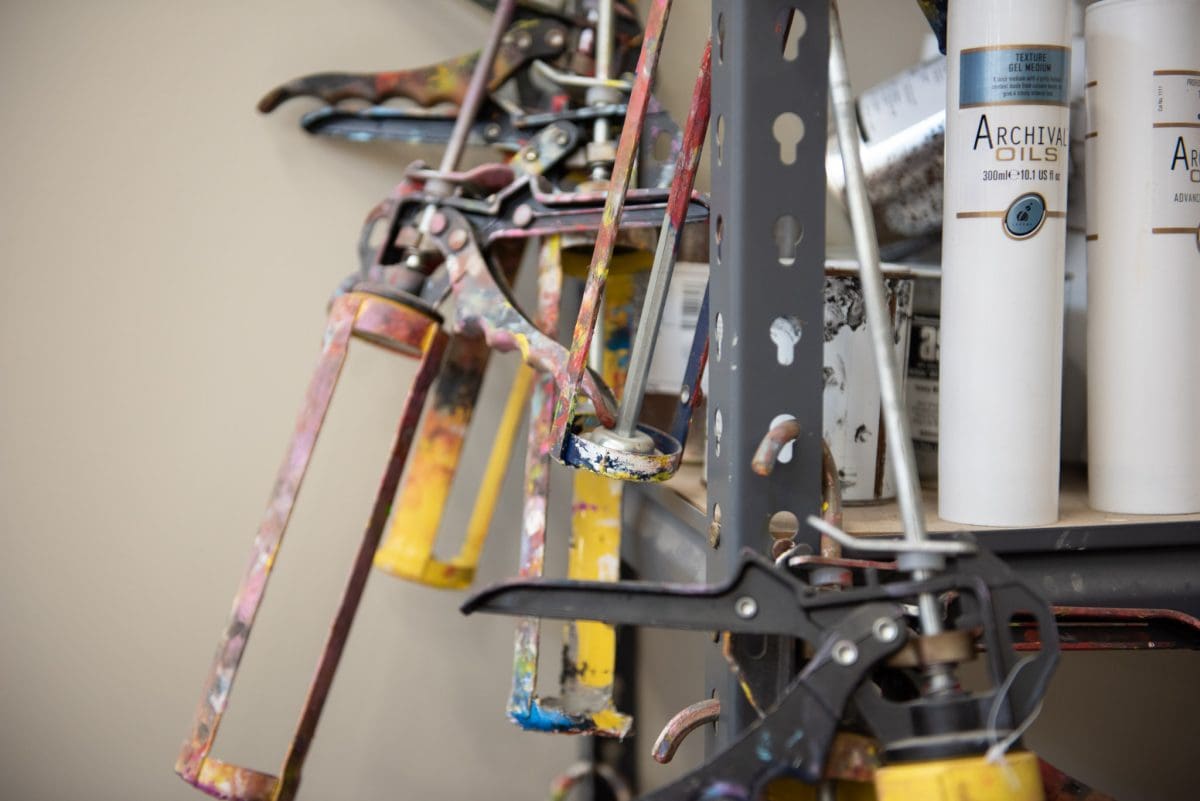

Also, I like that this studio is in a warehouse environment. It’s open, but private, and not too clean. So I feel like I can actually make a mess. Working in something like ceramics you accumulate a lot of clutter: boards, sponges, dollies, trollies, brushes, rags, bits of foam, blankets. It’s hard to have a sexy studio working with a material like this. Here, I just feel a little bit freer to do what I want!

PROCESS

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: One thing that really transformed the work was getting my own kiln. I bought it after I won the 2015 Sidney Myer fund Australian ceramic award. I was like, “Oh, I’ve got some cash, I need to invest in capital!” It’s like 600 kilos of baggage, but I just thought, “I’m going to do it.” For an artist who actually wants to experiment with materials and take risks, borrowing kilns just isn’t viable.

I don’t really have a studio routine. In the last six months I’ve probably been here six days a week, but I love it. I’m often doing as many firings as I can during the week, so I might have a meeting in the morning, then I need to come here and pack the kiln, and then turn it on after hours because the first few hundred degrees of the firing lets off carbon monoxide and we don’t want to be here during that. So there’s a lot of timing that’s actually structured around the firing processes. I could just wait for the next morning, but I might come back at ten o’clock at night. It’s always kind of exciting opening the kiln door.

There are so many stages of transformation when glazing. I use commercially bought glazes. However, I edit them, I layer them. And I use highly saturated colours, but a lot of them go on grey. Alchemy is a clich d word to use, but you know, it’s almost like that. I think a ceramics person would say my glazing process is quite experimental, but I see it more as a painterly aesthetic.

My diaries are central to all my work. I usually have ideas all the time. So I do a little scribble, and loose watercolours, and I can come back and it reminds me of what I was thinking.

PROJECTS

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran: What drives all of my work, no matter what the scale, is an interest in histories of figurative representation, and especially idolatry in the context of South Asia—but from an imaginative or rhetorical position. I’m not interested in realism.

My large-scale projects—like the 2021 HOTA [Home of the Arts] and Dark Mofo commissions— need engineering and technical drawings. So arriving at a conceptual full stop is important quite early. At the start of these processes, I work on developing the sculptural language by drawing, collaging, building maquettes, colour testing. And discussions with Mark Dyson [a lighting designer], who manages a lot of my large projects, are ongoing.

Whereas the ceramics are more fluid; there are more unpredictable processes. There is a lot of repetitive labour and they often take months to make. I have studio assistants who come in two days a week. And there is so much cleaning, so it’s great to do that stuff in pairs. But the final layer of glaze, all the crazy bits, all the expressive stuff—the faces, the carving, the real painterly gestures—I have to do that.

I do quite a bit of painting actually; not in comparison to the amount of sculpture I make, but I still do paint and draw. I have two paintings in the summer group show, Art Mixtape, at HOTA. And I’ve been working on a public art project for the Sydney Metro Station in Marrickville: colour photographs in glass panels, like terracotta clay dioramas, a new technology for me. It’s meant to open in January. Also in January I have a solo show in Mumbai at Jhaveri Contemporary. I have so much going on all the time; I just hustle to get everything done.

Art Mixtape: Yours for Summer

Group exhibition

HOTA (Home of the Arts)

18 December 2021—Ongoing

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.