Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

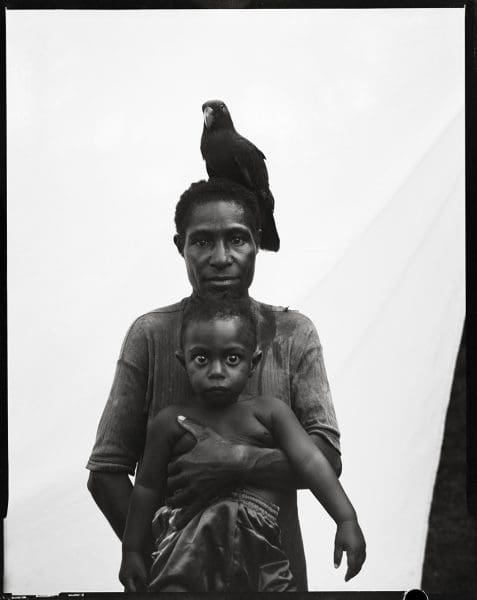

From the detribalisation of Papua New Guinea to internecine fighting in Afghanistan, the disappearing world of communist Cuba to the Sadhus holy men of India, Sydney-born Stephen Dupont’s photography bears witness to struggle, and captures human dignity alongside harsh reality, his focus on forgotten or untold stories. Yet the allure of portraiture eluded him, until the will of a crowd accidentally provided a rich context for portraying individual subjects, creating what he calls an “ultimate form of portraiture,” that mixes collaboration with spontaneity.

We meet over a meal of fish, squid, chips and beer at the Scarborough Hotel overlooking the sea, in the pretty NSW south coastal town where the 49-year-old photographer lives with his partner and daughter. Dupont has spent the morning surfing.

He has grown his hair longer than when we last met, in 2013, when he was helming Sydney’s Reportage photojournalism festival. Life is hectic, despite this idyll: he’s the subject himself of an upcoming, partly biographical National Geographic documentary, one episode of a three-part series, Tales by Light, each focusing on one of three photographers.

Dupont’s episode, to air on the Nine network in early November, follows him through several countries as he examines the rituals of death in many permutations, be it human or cultural death.

He has found the experience cathartic, an aid to mentally processing what he has witnessed over several decades, such as a devastating 2008 Taliban suicide bombing during a poppy eradication expedition in Nangarhar province in Afghanistan.

There is another film he is collaborating on, with Rats in the Ranks documentary filmmaker Bob Connolly. The subjects are New Guinea’s highland people whose first western contact was only in the 1930s, but who are rapidly being shunted into modernity with globalisation and mobile phones. That film is likely to be released at film festivals next year.

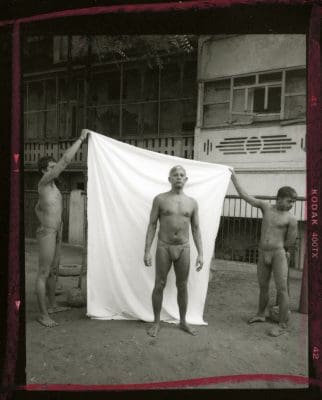

Capture a person in front of a plain backdrop, thereby rendering the subject with little distraction and supposed objectivity.

Ethnographers, of course, often historically used this approach to inveigle colonised Indigenous peoples into racially loaded, bogus scientific schema of noble savagery.

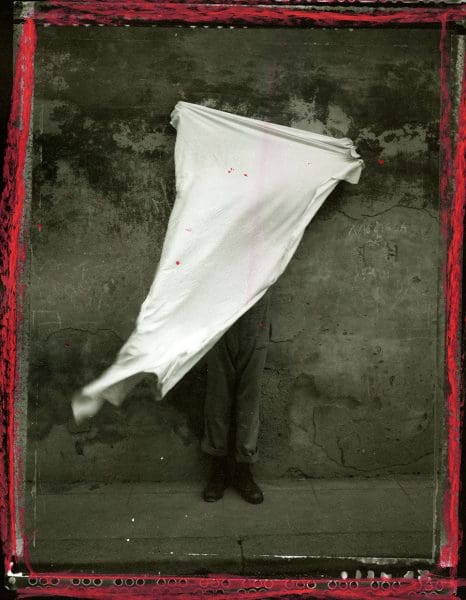

In Kabul in Afghanistan in 2006, Dupont explains, he had begun photographing 100 people on Polaroids in an afternoon for portraits, with a borrowed backdrop, in a prelude to the series that became Axe Me Biggie.

Dupont’s assistant would tell curious locals gathering to see the photography taking place to move away. “It got to the point where we couldn’t control the crowd any more,” he recalls, “and I just took the pictures anyway.”

Peeling away the Polaroids was a revelation: “I started to understand, ‘Shit, I’m doing the wrong thing; I should just let things happen. I shouldn’t try to push people away’. When people came into frame, it was producing these wonderful, magical images.”

Awarded a Gardner Fellowship in 2010 at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Dupont looked at 19th-century photographic studies by anthropologists in Africa.

“They were quite crude and racist, really, in a lot of ways, those early pictures. They were photographing ‘savages’ and the ‘other’. I found the photos very confronting. I wanted to explore something around that style, but in a more modern context.”

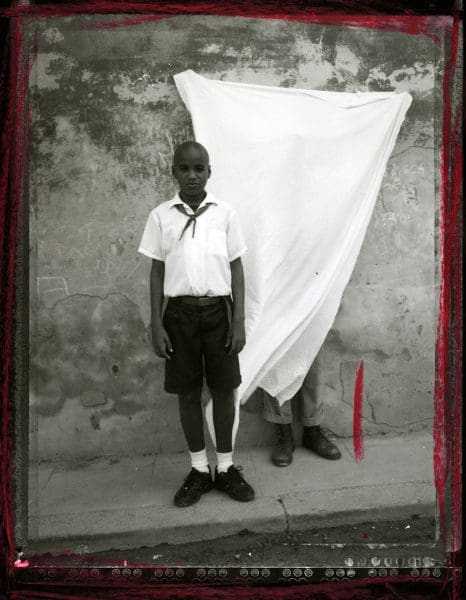

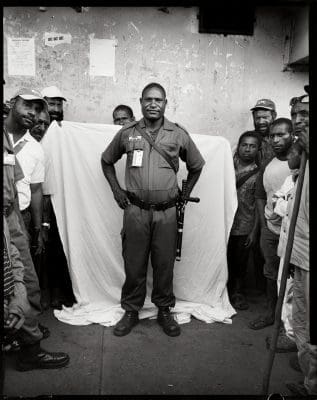

Dupont took to carrying a single white sheet as a portrait backdrop with him on assignment and photographic expeditions, allowing the sheet to become wrinkled and grubby, even showing its edges within the image frame.

In each location, he would ask local people to hold the sheet up, and spontaneously include the audience in the background.

“The photographs honoured not only the subject, but everything going on around them,” says Dupont, pleased at this melding of portraiture with documentary photography, which has always been the heart of his art. “For me, it feels like the ultimate environmental portrait.”

The White Sheet Series exhibition will include portraits taken in New Guinea, India, Cuba and – at the time of this interview, still to be taken – racegoers at Sydney’s Randwick, with all their feathers and finery likely to oddly echo the tribal dresses of the Indigenous Melanesians of our Pacific neighbourhood.

Dupont is acutely aware his white gaze from affluent Australia carries its own cultural baggage.

“You can’t get away from that; there is still an acknowledgment you are this ‘outsider’, and they are the ‘other’, but what is honest and respectful is that you have the collaboration with your subject,” he says.

“With all my photographs, I’m not ‘stealing’ something; I’m actually working with the subjects to make these photographs. But I’m also, in a secret sort of way, establishing what’s going on in the background, where people aren’t so aware of being photographed.

“They [the crowd] don’t become the subject of the photograph, but they are part of it, and in many ways make the photograph work. I like that mystery and spontaneity.”

Stephen Dupont

The White Sheet Series

Stills Gallery, Paddington

9 November – 10 December