Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Indigenous photographic artist Darren Siwes has found just the right old house in Adelaide, one with 1940s Axminster carpets, fireplace and period furnishings, to which he is bringing clothes of the same era. Next, Siwes, who is of Dalabon heritage from Arnhem Land as well as Dutch descent, is flying Aboriginal relatives from the Northern Territory to pose for a photo shoot.

“Clearly, it’s about cultural domination of Indigenous Australians,” says Paul Greenaway, who has put together a quartet of artists, two of whom identify strongly with their Aboriginal heritage, presenting all-new works for a group show in his Kent Town gallery.

While there is no overarching theme to the group show at GAG Projects, colonial skewing of history and cultural clash emerge as through-lines for the three male artists. “It’s four very strong South Australian artists who I think all are at the top of their game at the moment,” says Greenaway.

The gallerist founded the South Australian Living Artists (SALA) Festival in 1998, running the festival for its first 13 years. For the past 20 years of the festival he has showcased a single South Australian artist; this year, he has changed the formula to put four local resident artists in the spotlight.

Previously, Siwes has satirised imperialist power: his striking 2013 series Mulaga Gudjere (Man Woman), held in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, for instance, posed Aboriginal people whose bodies were painted white and then dressed in regalia as sovereign heads of state, in naval cap, tiara and blue sashes. Siwes is now “back in full swing and his life is back on track”, says Greenaway.

Mildura-born James Tylor, who is of Nunga (Kaurna), Māori (Te Arawa) and European ancestry, has meanwhile built a career with photography too, using analogue and digital means while experimenting with daguerreotype, a process used to document Aboriginal culture and European colonisation.

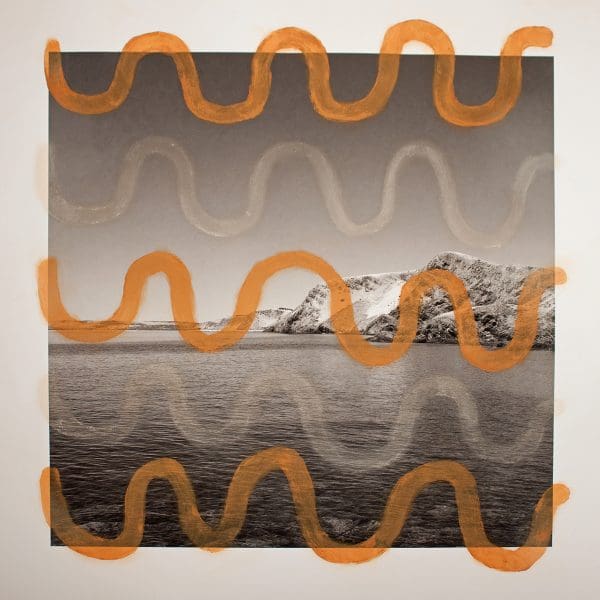

Tylor’s new works are about place, photographing sites of massacres and other Indigenous cultural importance, and he has hand-painted simple geometric designs over the top with ochres sourced from the areas photographed. These 50 by 50 centimetre black and white works are printed on rag paper. Tylor is also carving small wooden objects to accompany the works.

The youngest member of the quartet is Pierre Mukeba, turning 23 this year, who has amassed a body of figurative work on canvas and cloth after living in South Australia for more than a decade, where he continues to be employed in retail and makes art after hours.

Born in 1995 in Congo, Mukeba’s family fled the ethnopolitical civil war of their homeland to a refugee camp in Zambia, where food was scarce, then onto Harare, the Zimbabwean capital, until then president Robert Mugabe cracked down on non-nationals of Zimbabwe. Facing potential arrest, the family applied for asylum at the Australian embassy, and were granted residency here in 2006.

His latest works continue the stories and images from his memory of the Congo, but this new series of portraits of women from his family – mother, aunties and sisters – look in part at how African women try to emulate European women, while expanding the artist’s palette.

The fourth artist whose works will be shown, Adelaide-born sculptor Julia Robinson, is employing historic references to 18th and 19th century writings on the male phallus. Her wall-based installations will provide a stark three-dimensional element that will o set the photographs and paintings of her male artist counterparts.

In the past, Robinson’s works have discussed the rituals of religion, the afterlife and death, drawing on myth and superstition. More recently, her sculpture practice has produced works invoking fertility and resurrection motifs. Death does not feature this time; rather, it’s an examination based on readings of “euphemisms and expressions used to talk about the penis, without actually talking about the penis,” says Greenaway.

The paintings present an uncanny echo of Darren Siwes’s photography depicting Indigenous Australians being forced to wear European clothing. “When Pierre started painting these works and sewing fabric onto the canvas, drawing as well, he wasn’t even aware that so-called African fabrics were made in Holland,” says Greenaway. “The whole colonialism thing pops its head up again.” Mukeba will also have a solo show as part of the Melbourne Art Fair in August.

SALA Exhibition

GAG Projects

25 July – 26 August