Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

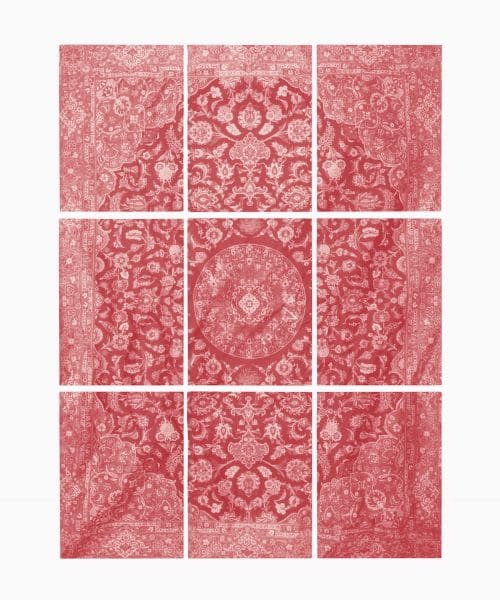

Stanislava Pinchuk, Red Paintings, 2020, 1.1 x 1.5 m each, 3.6 x 4.8 metres (overall, framed). © the artist.

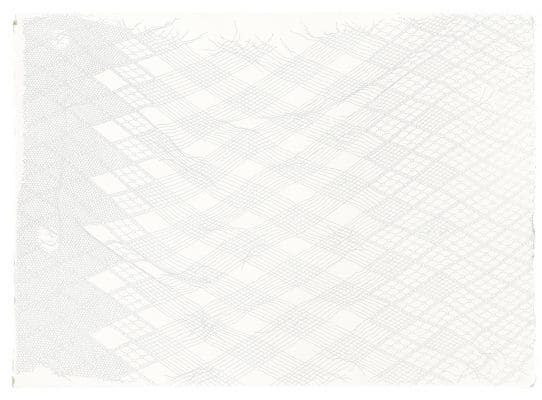

Stanislava Pinchuk, Data Map: Topography: Contaminated Soil Storage, Fukushima Nuclear Exclusion Zone, 2016, pin holes on paper, 75 x 101 cm. private collection © the artist.

Stanislava Pinchuk, Calais ‘Jungle’ Terrazzo V, 2018, camp remnants and ash resin, 18.5 x 11 x 5 cm. private collection © the artist.

There’s a myth that landscapes are neutral, as blank as stage sets. But Stanislava Pinchuk understands that the spaces we move through are alive with energy. They hold the patina of human experience, accrued over time. You can walk into a room, the artist says, and know that people have fought there; you can enter a space after someone has prayed, and feel a sense of elation.

“It’s hard to deny the Holocaust when you are in Auschwitz, and that there’s been an invasion in Ukraine when there is a bomb crater,” says Pinchuk, an artist whose site-based works deal with conflict, trauma and memory—the last five years of which are collected in the survey exhibition Terra Data at the Heide Museum of Modern Art. “Land, ground, air and water have such a profound capacity for memory and record and witness.”

And there is much to witness. Riots in Washington. An explosion in Lebanon. A London hospital overwhelmed by Covid-19 patients. We live in a world that asks us to process a magnitude of crises, as fast as the images which fly through our newsfeeds. Pinchuk is drawn to facts, figures and information, but her art charts disaster’s unseen topography in ways that bring a sense of slowness to global events.

Over the last seven years the artist has used various elements of data—collected from conflicts such as the Ukranian Civil War, and the nuclear disasters at Fukushima and Chernobyl—and has ‘mapped’ this data by making tiny pin-holes in paper; all in figurations that are beguiling in their own right.

For Pinchuk, the forces of history may remake countries but they also redraw our personal borders. She believes that bodies and land are part of one continuum, and she has long etched intricate handpoked tattoos on her friends. “If there is an art medium that is painful and time consuming and difficult,” she jokes, “I am there.”

Based in Melbourne for the moment, Pinchuk was born in Kharkiv, north-eastern Ukraine, in 1988—only two years after an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant spelled catastrophe. “I was a shy kid; I really loved drawing and reading,” says the artist, who became obsessed with the greats of Russian literature.

She moved with her family to Melbourne at 10 years old. “As a teenager, I got into punk,” she recalls. “I realised you could make things.” Soon after, her delicate paste-ups of women, made under the name Miso, started flanking the city’s doorways and corners. Her first solo show was at 19, and success followed.

But in her late twenties Pinchuk experienced a “rupture.” In 2013, pro-democracy protests erupted in Kiev’s Maidan Square. By April, pro-Russian separatist rebels, armed with surface-to-air missiles, started seizing Ukrainian territory. In August, Russia invaded, and Pinchuk’s home country was embroiled in conflict.

“I come from generation after generation of people torn by war and genocide, but it wasn’t something I expected to see in my lifetime,” she says. “I was going through a huge break-up. I just stayed in my studio for six months and made work.”

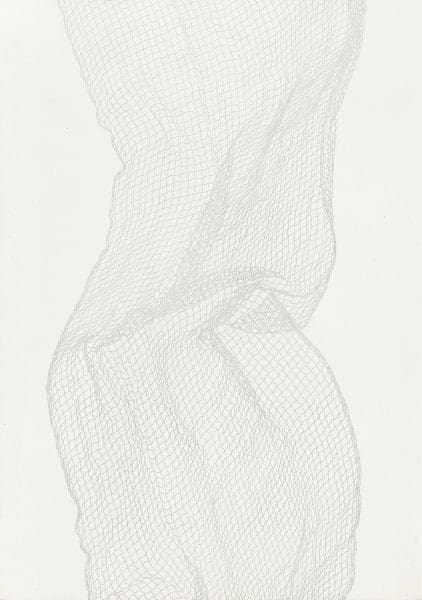

Surface to Air, which showed at Karen Woodbury Gallery in 2015 and drew upon Pinchuk’s experience and knowledge of this recent Ukrainian conflict, featured drawings resembling swathes of fabric. Up close, they comprise constellations of tiny pinpricks, each corresponding to a piece of data gleaned in the conflict zone, created painstakingly with the tip of a book-binding awl.

While the public face of war has always been male, Pinchuk notes how women have historically documented conflict by making medieval battle tapestries and Afghan war rugs. “Textiles [were] the medium available for women to express themselves,” she says. Here, the intimacy of cloth is made apparent. It moulds to our bodies, responds to movements, and speaks to life in a war zone as an emotional and visceral experience that registers on our skin.

Pinchuk’s art asks what it means to personally live through history. For example, in putting together her 2017 work Sarcophagus, Pinchuk visited Chernobyl’s Reactor 4. She used a Geiger counter to measure the levels of radioactivity in the ground before and after 1986; before and after the Chernobyl disaster.

“It made me realise how much I grew up in Chernobyl’s shadow,” says Pinchuk, who comes from a family of lace-makers and bee-keepers, and plotted the data as a 6-metre drawing that referenced bridal lace and bee-keeping veils. “We have culturally enforced amnesia for a lot of reasons. [But] it is very hard [to deny] when it is written on the land.”

Most recently, in 2020, Pinchuk blanketed the steps of the Opera House with a Bessarabian rug, a style of carpet that originated in Ukraine and Moldova in the 19th century, and interweaves Persian, Central Asian and French influences.

The work, presented as an image called The Red Carpet, which is being shown for the first time at Heide, incorporates a data-map of the Maidan Square protests (the aforementioned protests that took place in Ukraine in 2013). The Red Carpet also documents Australia’s bushfire season, and acts as a love letter to Jørn Utzon, a Danish architect who didn’t believe in hierarchies between decorative arts and architecture.

While the rug has deeply personal implications for Pinchuk and her complex relation to Ukraine, to me it also asks this: how do we find a sense of home when the world is burning, when the histories that have formed us are yet to be voiced?

Terra Data

Stanislava Pinchuk

Heide Museum of Modern Art

20 March—20 June