Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Collaboration is at the heart of Circumbinary Orbits, a series of three exhibitions presented back to back at Contemporary Art Tasmania (CAT). Each exhibition involves two artists, one presenting work and the other curating. Overseen by CAT curator Kylie Johnson, each pairing looks at major elements of the presenting artist’s practice and how these have been developed into new work within a collaborative process. Starting in late September, the Circumbinary Orbits exhibitions encompass the pairings of Matt Coyle and Joel Crosswell, Lou Conboy and Mark Shorter, and Julie Fragar and Amanda Davies.

Each pairing has spent the last few months working through the unpredictable work environment COVID-19 has thrown in their path. Slated as the second exhibition in the Circumbinary Orbits program, An Unsteady Compass is the outcome of a collaboration between Lou Conboy and Mark Shorter. National lockdowns present less-than-ideal conditions for collaborative projects but, fortuitously, when Hobart-based Conboy first met Melbourne based Shorter, COVID-19 had yet to appear. Taking on the curatorial role, Shorter visited Conboy’s studio in Tasmania early on in the project. “We spoke about Lou’s previous work, the thinking behind it and the influence of her family,” he says. “She told me one of her female relatives had been involved in cabaret, which is interesting because Lou’s practice is heavily based in costumery. She isn’t just performing as herself but exploring ideas through character and a theatrical self.”

Continuing to meet up online during lockdown, Shorter remained a sounding board for Conboy’s ideas.

“Collaboration is always difficult, but I think what has made this actually work is that it was clear what our roles were from the beginning,” Shorter says. “We decided it was a chance for Lou to build a major body of work, so at the core of it, it’s a collaborative project but very much driven by Lou.”

Working across the mediums of photography, video and sculpture, Conboy’s vividly coloured visuals appear imbued with a crackling alchemic energy. Highlighting the overarching theme of her practice, Conboy says “an acceptance of the absurd” is key. Describing her creative process as “combining costume, landscape and stories to reveal and question bigger truths about how we live and interact with nature,” Conboy also points out that “the characters I create and photograph are spirits—residues of our combined pasts.”

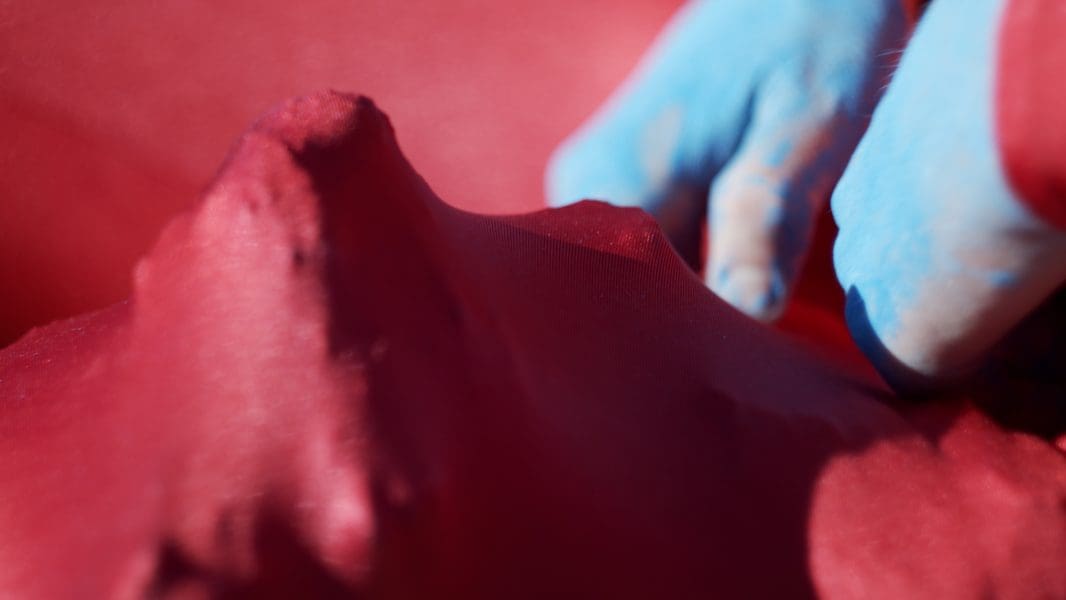

A recurring character in Conboy’s repertoire of costumed protagonists is Sisyphina, a flame-haired, lycra-clad woman of the hills. Drawing upon the Greek myth of Sisyphus, a Corinthian king condemned by Zeus to spend eternity rolling a boulder up a hill only to reach the top and have it roll back down, Conboy’s Sisyphina is often accompanied by rocks of various sizes. “Sisyphina is partly about how we hold grief,” explains Conboy. “For me, the rock represents so many things: patriarchy, sunk costs, the embryonic hatching of an idea, a struggle, a meditative moment.”

An Unsteady Compass marks the second time Conboy has incorporated Sisyphina into a major body of work. Initially part of the 2019 arts program at the Mona Foma festival in Launceston, Conboy exhibited a series of images depicting Sisyphina pushing a huge rock through mountainous locations in northern Tasmania. A year later, Sisyphina was still on Conboy’s mind. During a month-long residency at Q Bank Gallery in Queenstown, a former mining town on Tasmania’s West Coast, Conboy began conjuring a way for Sisyphina to engage with the scraped and craggy terrain. “The topography of Queenstown is incredible, but I was also really attracted to the grit of the community, the resilience to hardship and isolation,” says Conboy.

Under the umbrella of Circumbinary Orbits and with the curatorial guidance of Shorter, it was in Queenstown that An Unsteady Compass steadily came to fruition. Influenced by Geoffrey Blainey’s 1954 book, The Peaks of Lyell, and local stories of escaped convicts, goldrush fever and old photographs, Conboy’s new work follows Sisyphina as she traverses the rugged West Coast. Climbing across harsh terrain, at times she fills her red bodysuit with chunks of ancient rock, slowing her pace and almost becoming part of the landscape herself. The site of the defunct Mount Lyell mine also plays a significant role as the backdrop to many of the images, as Conboy goes on to explain: “I made the work facing the mine as it was impossible not to respond to this weird, barren landscape with mountains of iron tailings.”

For Shorter, his curatorial role in An Unsteady Compass was a contrast from his usual practice as an artist working with public performance and installation. Like Conboy’s alter-ego of Sisyphina, Shorter also performs characters of his own, including landscape critic Schleimgurgeln, voyager Tino La Bamba and the spectacularly rhinestoned Renny Kodgers.

While there was an opportunity to include his own work in the exhibition, Shorter chose to maintain his role as a mentor rather than participant. “I was there to lend a critical eye to strategies of working with the body and the camera to develop an idea,” he says. “To question how you might observe and explore your surroundings to communicate how your body sits within it. An Unsteady Compass is quite an open work. It’s simply asking—how do we navigate the mythologies written over the landscape and the mythologies we carry within us?”

Circumbinary Orbits: The Cut

Julie Fragar

Curator: Amanda Davies

26 September—4 October

Circumbinary Orbits: An Unsteady Compass

Lou Conboy

Curator: Mark Shorter

3 October—18 October

Circumbinary Orbits: Transmission Line

Matt Coyle

Curator: Joel Crosswell

10 October—25 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.