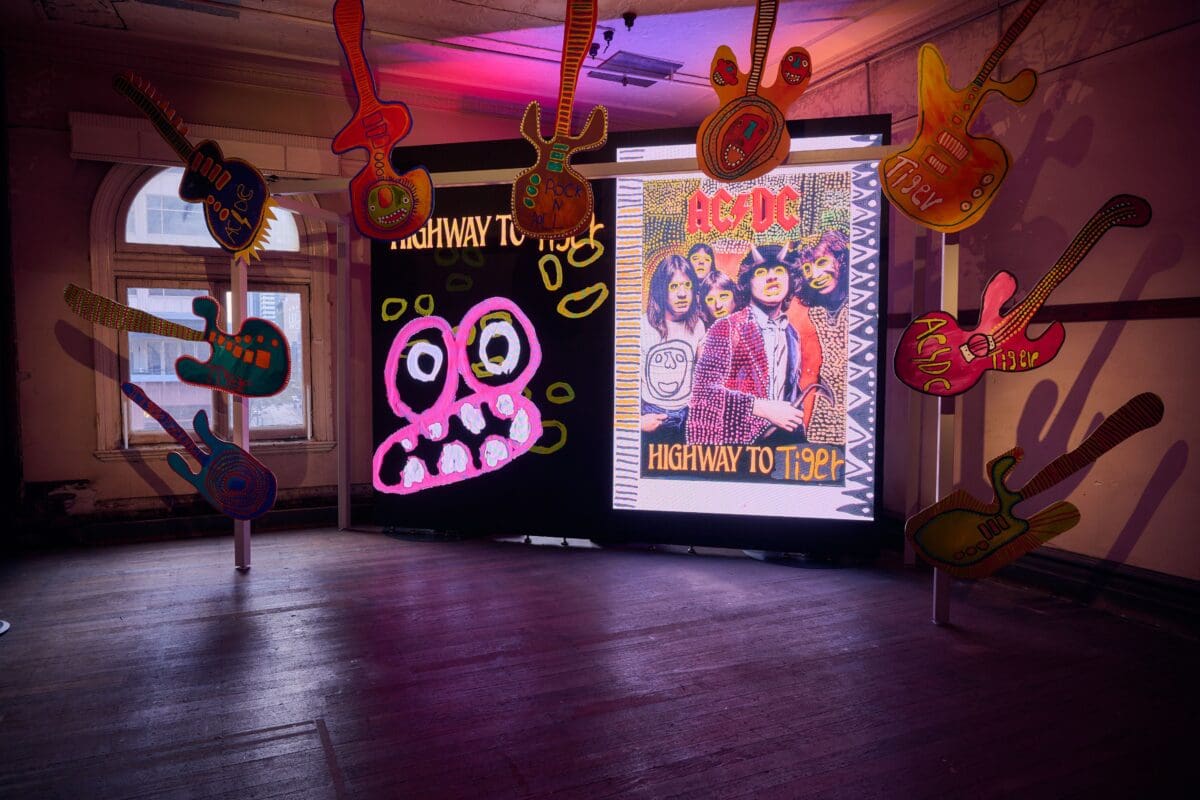

ROCK N ROLL, 2023, Tiger Yaltangki-Yankunytjatjara with Jeremy Whiskey–Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara.

Karla Dickens–Wiradjuri, Deeply Rooted, 2023.

Brian Robinson–Maluyligal/Wuthathi, Zugubal: The Winds and Tides set the Pace, 2023.

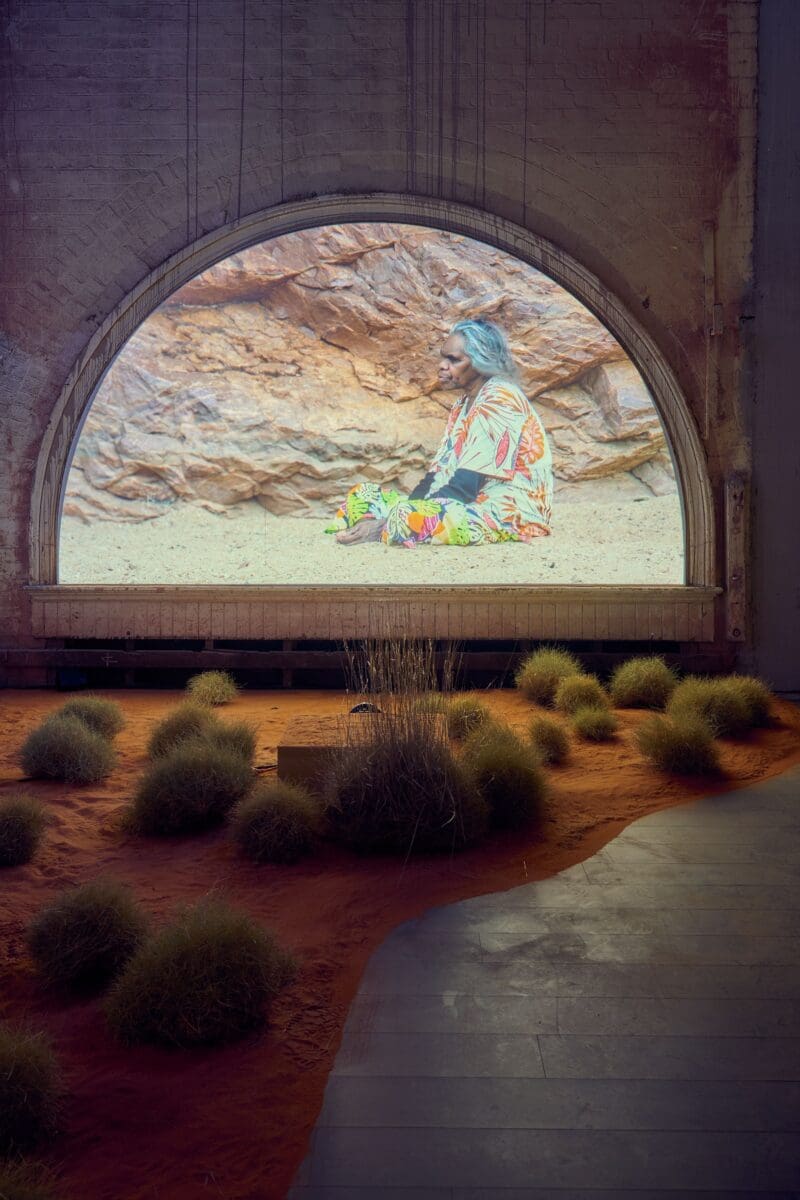

Rene Wanuny Kulitja-Pitjantjatjara, Tiirtjingalpai–practicing care for the spirits of the dead, 2023.

The Mulka Project and Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda (NT)–Yolŋu, Rarrirarri, 2023.

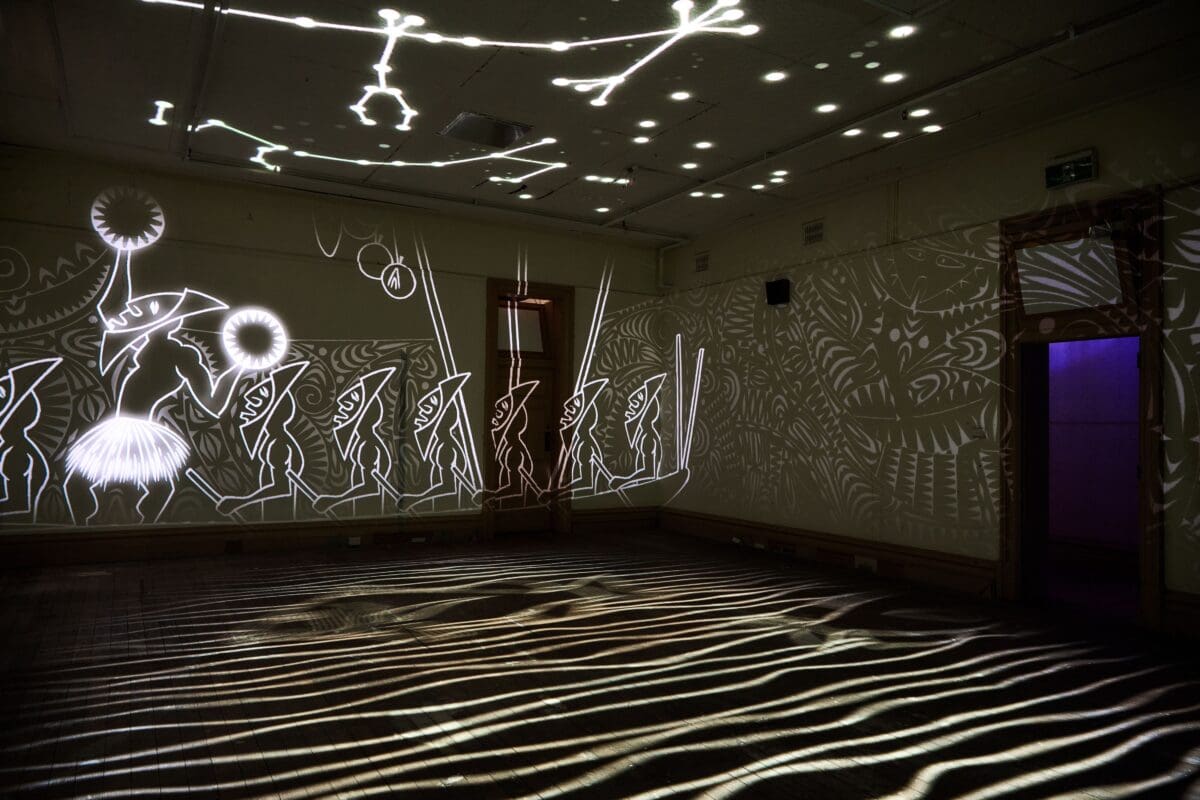

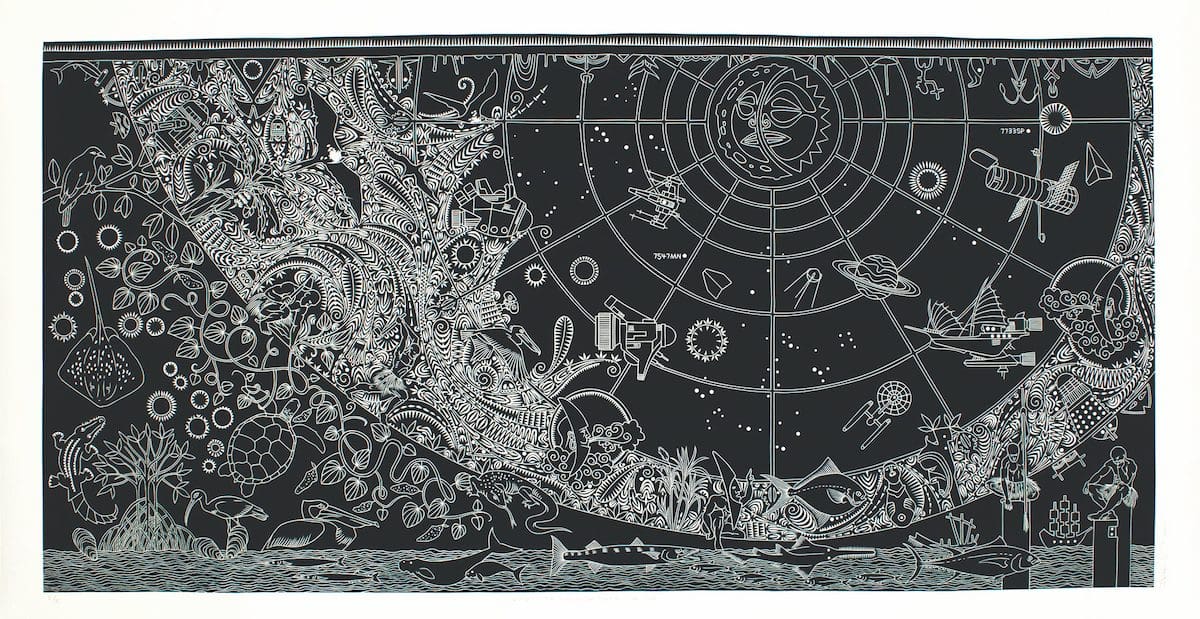

Brian Robinson, Zugubal: The Winds and the Tides set the Pace, 2023, immersive room animation created from black and white vinylcut prints done in collaboration with S1T2.

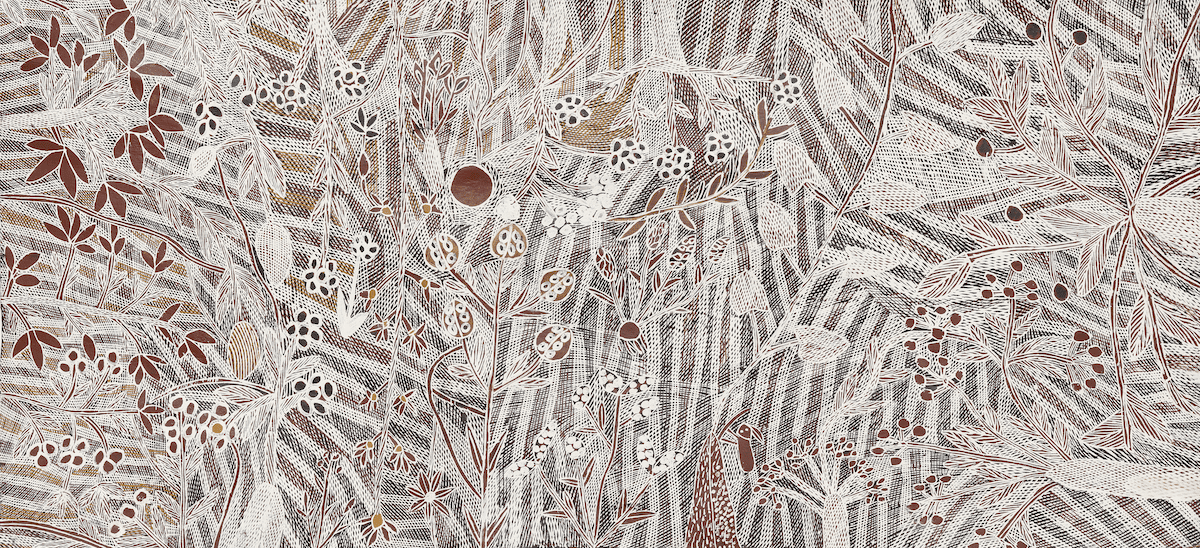

The Mulka Project and Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Retja 1 – Rainforest 1.

The Birrarung (Yarra) River was a gathering place for the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation from time immemorial. And yet for a comparatively short 169 years the river’s south bank has been the home of Australia’s first railway station, Flinders St. Opening in 1854 and initially known as Melbourne Terminus, it’s a complicated site of colonial history and contemporary commuter congregation.

Now, the station’s upper levels are having a spiritual transformation. Above the famous clocks in the main building, in grand old rooms completed in 1909 but sealed off to the public and only reopened recently, are First Peoples’ connections to the spirit world, Country, metaphysics and memory. Transported multiple stories above the commuter and city bustle, linear time is left behind in Shadow Spirit.

An ambitious exhibition, Shadow Spirit, as part of Melbourne’s RISING Festival, will present 14 new, large-scale commissions involving 30 Indigenous artists from across the country. With about 100 specialist fabricators also in the mix, alongside mediums of animation, sculpture and sound, it’s centred on evoking Indigenous understandings of the spirit world in the widest sense.

In the grand ballroom, where people once paired in dance, the Mulka Project from the Northern Territory will immerse audiences in Rarrirarri. The collective are animating and mapping the botanical, animal and spiritual designs of Yolngu artist Mrs. Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, an Elder who died in 2021. The multi-projection work comes with surround sound, and follows her footsteps through a forest of her designs.

“It’s very exciting and it’s such an honour to have this work coming in,” says Kimberley Moulton, a Yorta Yorta woman and the exhibition curator. In honouring Mrs Wirrpanda’s spirit through ceremony, songlines and the ecology via technological means, “it really encapsulates the whole show”.

Moulton, who ideally wants the exhibition to tour locally and internationally, has been working with Indigenous artists for over 15 years, recognising among the multitude of cultural histories a common thread of spirituality. There will be light and dark moments, she affirms, with a sense of spirituality offering “beautiful conversations between the artworks … and the breadth of First People’s contemporary art practice and cultural knowledge. I hope that people can see the positivity and really celebrate that.”

The non-linear emphasis means “you will walk into Flinders Street and experience each work as an individual story”, explains Moulton, who has chosen the artists partly through professional relationships, as well as artists whose work she admires.

In developing Shadow Spirit and its broad theme of connecting to the spirit world and systems of knowledge—as well as the shadows of colonial history—Moulton has chosen five subthemes: weaving time (astral plains, multiverse, dreamscape); spirit ecologies (Country-land, sky, water); the guides (protection, healing, play); absent presence (malevolent, warning); and the in-between (memory and shape shifting).

Embodying ‘weaving time’ is Waiben-born (Thursday Island) Maluyligal/Wuthathi artist Brian Robinson. His work, Zugubal: The Winds and Tide Set the Pace, starts with two of his large linocuts made in his Cairns studio, before immersing audiences in an animation of zugubal, who are celestial beings, along with the pop culture surprises of PacMan and storm troopers.

Robinson’s work is informed by childhood experiences of island life, from floral blooms to seasonal winds, to the tides and monsoons, and what lies beyond. He’s also influenced by history and the contemporary: from the sorcerers who once danced in masks on Waiben (Thursday Island) to the stash of Phantom comics his grandfather shared with him.

Yet the central figure are the zugubal, which begin life as constellations. “They’re spiritual beings, star clusters that influence life back on Earth, especially through the Torres Strait, where the zugubal spirits lie,” he says, pinpointing the “tagai” star cluster in particular.

Further exhibiting is the projected artwork Mok Mok, by Wemba Wemba / Guntidjmara artist Paola Balla. In this performative piece, Balla dresses as the spirit figure Mok Mok, which is variously described as a devil woman and sovereign goddess. For Balla, her personification of Mok Mok is a moral response to male violence and to the objectifying Western gaze on Indigenous women.

Balla first learned about Mok Mok from her strong Indigenous mother and grandmother, and she’s approaching this work with a love of both horror and humour. Like her late grandmother, she loves frightening and surprising people, daring them to enter the eerie space she’s creating.

Audiences will be surrounded by three screens and bush-dyed fabric clamped to metal frames, resembling a stylised Aboriginal mission house— Balla’s great-grandparents walked off Moonahcullah mission in Wemba Wemba Country in protest at mistreatment by a mission manager.

Mok Mok will appear and disappear on these fabrics. “On first glance, is she a part of that fabric?” says Balla. “Where is she going to appear next? That’s really empowering for an Aboriginal woman entity, to have that power, instead of what constantly happens to us: being decentred and disempowered in this place.”

Shadow Spirit

Flinders Street Station, as part of RISING Festival

7 June—30 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.