Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Robert Smithson: Time Crystals is not an exhibition that you can take in on opening night. The 3D works, two videos, slide show and photographs, together with a glass cases full of writings and a multitude of drawings, diagrams and books require the surrender of time. A second visit, within the quiet atmosphere of dark walls and curtained areas, was required for immersion into the cult of Robert Smithson (1938-1973).

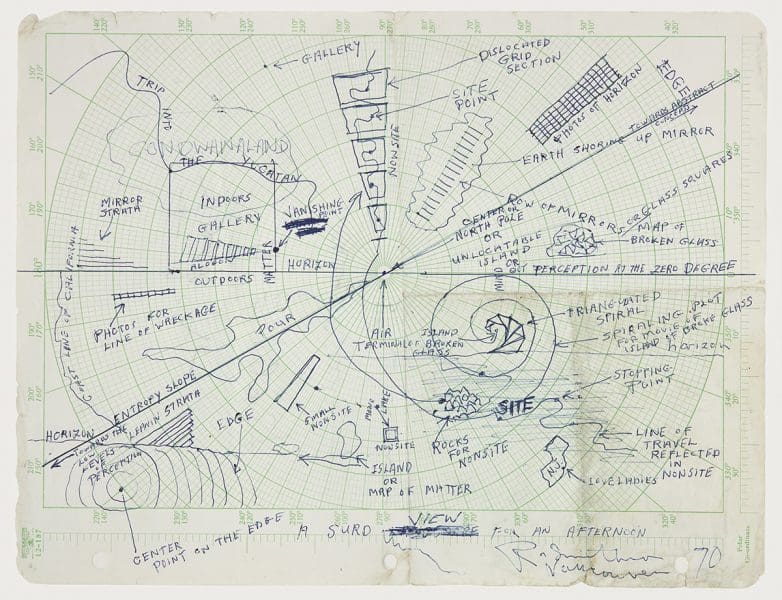

His extraordinary artistic longevity, given his short career which was terminated by an early death at only 35 years old, is explained by co-curator Chris McAuliffe from the Australian National University, as “to do with how he worked and his historical moment. He was among the first to make writing a prominent part of his practice… so when there was a major turn toward theory in American art at the end of the 1970s, Smithson was identified as an exemplar of postmodernism. And he pushed the idea of an artist as a project-oriented artist-administrator further than many of his peers.” Smithson became a self-described “conscious artist”.

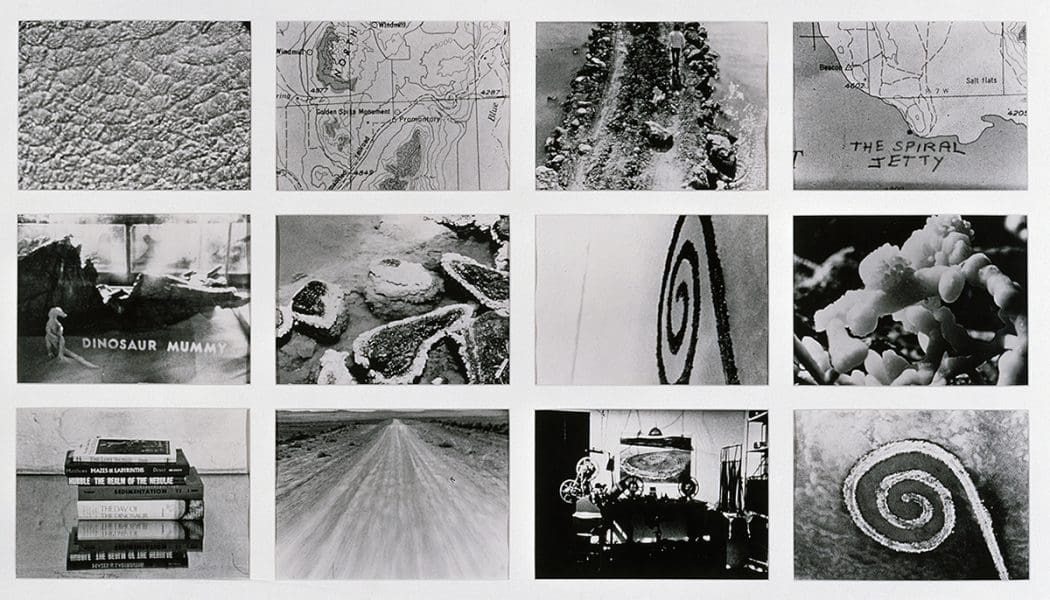

In this first exhibition of Smithson’s work in Australia, McAuliffe and Amelia Barikin from the University of Queensland construct his case. Smithson is best known for Spiral Jetty, 1970, located on the shores of Great Salt Lake, Utah. This iconic land art work is present in a film (now digital), Spiral Jetty, 1970. Among details of salt crystals, maps and the editing suite, we see Smithson himself walking and running the length of the jetty, and aerial views that allow the scale of the work to be experienced.

The crux of the exhibition for me, however, exists in a recorded Smithson lecture, Hotel Palenque 1972. Smithson speaks about a trip to Mexico and presented an unfinished hotel building as if it was an archaeological site. This rambling narrative, infused with a laconic humour, runs for 43 minutes, and becomes starkly illustrative of his visual interests. As the artist wrote in 1966, “I’m interested for the most part in what’s not happening, that area between events that could be called the gap”.

Smithson’s voice accompanies what the co-curators describe as the “motionless intervals” of the exhibition, including the film Swamp, 1971, its six minutes of camera judder creating nausea. Objects include Rocks and Mirror Square II, 1971, from the National Gallery of Australia, which takes viewers into a landscape of the rocks themselves, with their repetition in the square of mirrors into infinity (if you lie on the gallery floor to view it). Mirror/Vortex, 1965, expands endlessly, dissolving form, as you look inside.

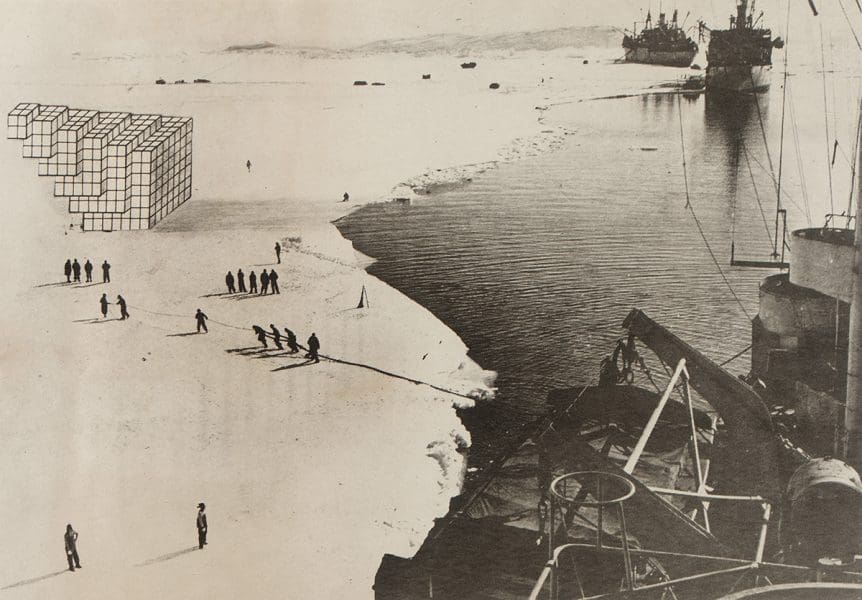

The title of the exhibition, Time Crystals, was a term Smithson coined in 1967. Within it he explained that he hoped to create a timeless, non-linear space in which “both past and future are placed into an objective present”. His writing conveys his ideas about the historiography of art, taking art into nature and nature into art. His attraction to crystals was due to their non-linear model of time and their ability to grow without being alive; to develop without evolution, a static yet fractured appearance.

The majority of the exhibition is drawn from the Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt papers in the Archives of American Art (Smithsonian Institution). The stilling of his time after his death was ameliorated by the efforts of wife/artist Nancy Holt whose bequest has ensured the preservation of this archival time capsule. McAuliffe said, “In part, his story is about unfinished business and speculation about where he was heading; the archives are crucial to that story.” This exhibition offers up a journey into Smithson’s conceptual interests, with an investment of sufficient time, they become intriguing.

Robert Smithson: Time Crystals

The University of Queensland Art Museum

10 March – 8 July 2018

Monash University Museum of Art

21 July – 22 September 2018