What does it mean to be a contemporary urban Aboriginal artist in Australia today? What changes have art institutions made in the past 20 years relating to Indigenous art and culture? And how do you start a collective? These are just some of the questions and issues yarned about during a lively discussion at the National Art School (NAS) in Sydney with members of the proppaNOW artist collective, which formed in Brisbane in 2003.

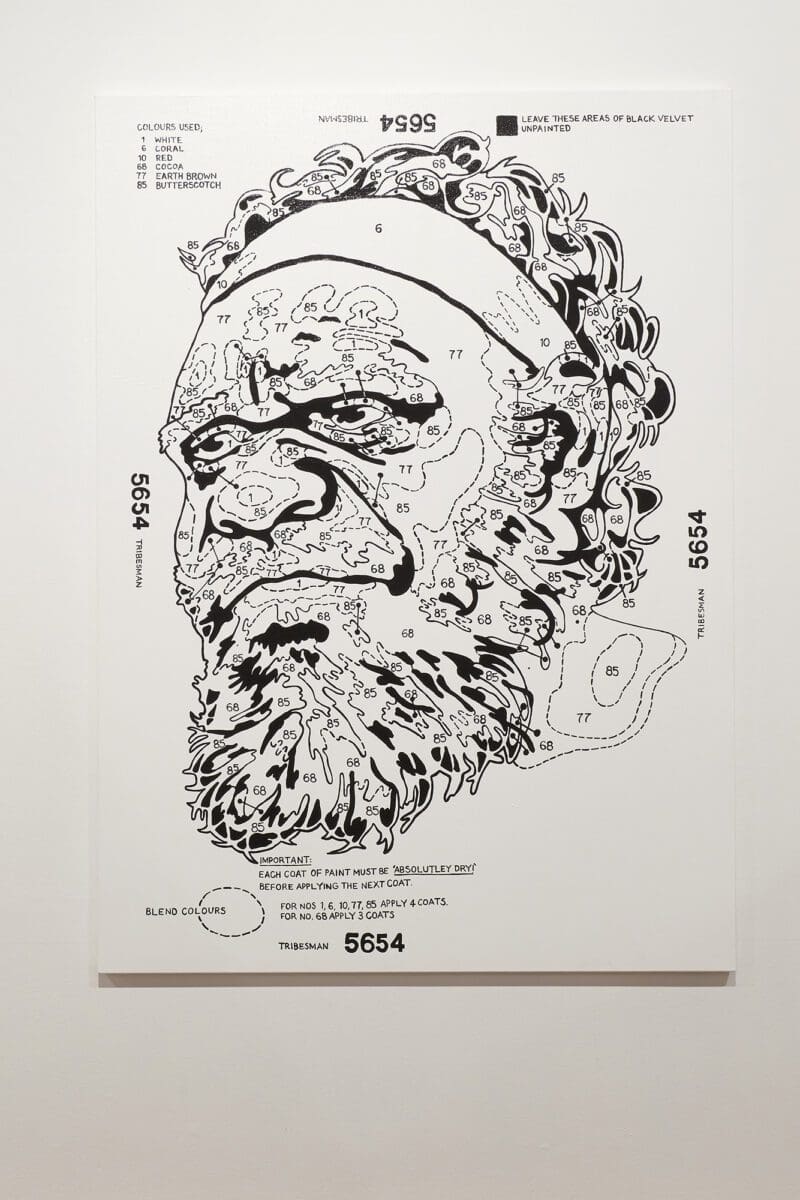

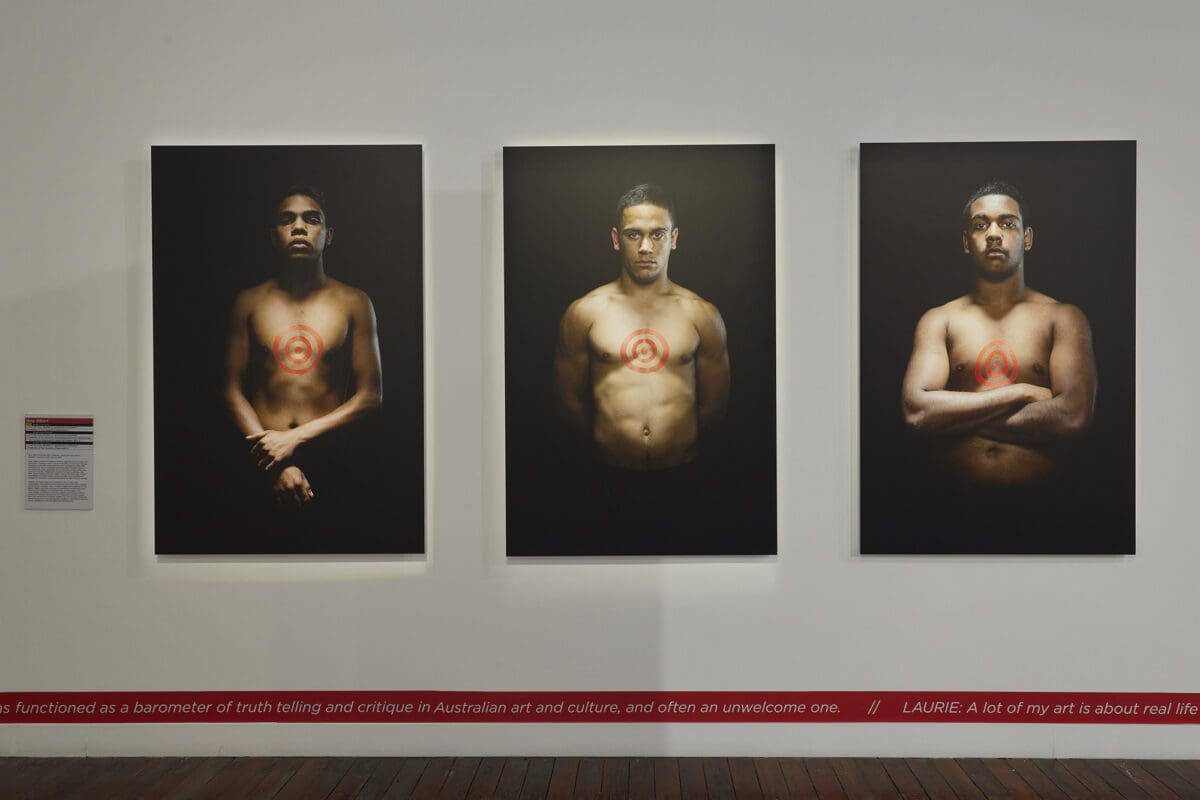

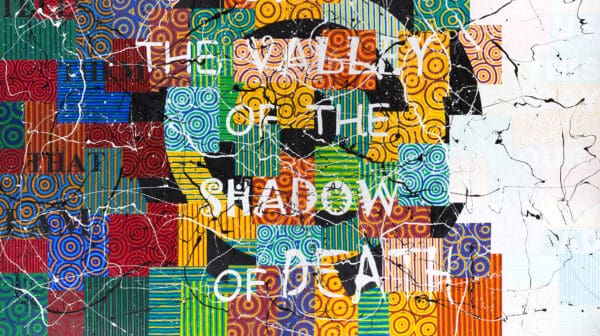

NAS is currently showing OCCURRENT AFFAIR, which features proppaNOW artists Vernon Ah Kee, Tony Albert, Richard Bell, Megan Cope, Jennifer Herd, Gordon Hookey and Laurie Nilsen.

Albert, Cope and Hookey, alongside new proppaNOW members Lily Eather and Warraba Weatherall, gathered to talk about the collective, institutional exhibiting, and speaking truth to power.

Dr Stephen Gilchrist from the University of Western Australia chairs the warm yet honest conversation, and began by acknowledging the panel took place on Gadigal land, and paying respects to ancestors of the past, present and future.

Stephen Gilchrist: We are here to celebrate an auspicious occasion. It’s the 20th anniversary of the proppaNOW collective and it’s also the first time you’ve shown as a collective in Sydney. I’d like to take you back to 2003 when you put out your first press release, it’s one of the first things you see when you enter the OCCURRENT AFFAIR exhibition. It’s been beautifully animated and echoes Martin Luther King’s 1963 speech ‘I Have a Dream’.

You mentioned [in the press release] a number of big picture ideas, and I’ll pull out a few of them: the establishment of autonomous Aboriginal art departments; Queensland Art Gallery to purchase work by more living Queensland Aboriginal artists; acquisitions to be made in consultation with respected members of the Aboriginal Committee; and no institutional employee shall stay in the job for more than five years. So, I was wondering if you could comment on one or all of these provocations, and if some of those still have a particular hold over your thinking.

“As a conduit between an institution and the community that is really super important because again, from the outside looking in, there can be decisions that could be deemed disrespectful or misunderstood.”

Gordon Hookey: I think with all of our members here, we relate to things differently. Even though we move and act in one voice, we’re all individuals. But to pick one of the elements of your question, we do strive to make the sort of art commenting on the moment and right now, we want that to be paramount especially towards the institutions because in my experience when people look at blackfella art or Aboriginal art, they think it’s dots and barks and comes from remote areas when in fact it doesn’t. So, I guess the main thing driving us from my perspective is to get the recognition that is due for urban artists like us.

Tony Albert: The only thing for me now is maybe I’d have a 10-year instead of five-year limit for institutional workers. But the point within that statement, if you have done what you wanted to do in your tenure at an institution, why are you still there? And if you haven’t done it, why are you still there? We so rely on those people inside the institutions for that vision and that dream for what we want to be projected. It’s still about the opportunity for autonomy inside institutions—choice making, who is doing that, is significantly important.

And the last one was being guided by the local community—I’ve seen advisory groups being attached to institutions now, that happened in Queensland not long after. As a conduit between an institution and the community that is really super important because again, from the outside looking in, there can be decisions that could be deemed disrespectful or misunderstood.

So, things are changing but institutions have this very glacial pace of moving, which we’re all aware of, and that comes into policies and procedures and a lot of things that are also outside the scope of just the institution alone. These are all the things we discuss as artists, and we have high expectations because we expect that out of an institution.

Stephen Gilchrist: Warraba and Lily, you’re two of the three new members of proppaNOW, had you thought about what you would put out in your press release? Were there any challenges you wanted to put out to the industry to think about, to meet this historical moment? What’s your manifesto?

Lily Eather: I guess we speak a lot about more about Indigenous curatorship in the industry. And hopefully we can start providing that kind of thing.

Warraba Weatherall: I think we’re getting to a place within the Aboriginal arts sector where more people are paying attention to us. We’re not just contemporary artists, there’s a lineage between our old people and now, so we can’t separate cultural and museum collections, and actually having Aboriginal people in decision-making roles.

So, when we’re talking about repatriation, we’re talking about intellectual property and we’re talking about people having access to them, whether it’s mob reconnecting and regenerating cultural knowledge systems, or whether it’s non-Indigenous researchers and the ethics involved within that. With a lot of those things there needs to be more work. People have been doing it for a long time, but we still have so many ancestral human remains and cultural property within so many institutions around the country. I don’t want to just see it as a painting or a print, I want to see it as a lineage of creative practitioners and that this is one outlet, but we’re still needing to recover and repatriate and redistribute the power within those institutions.

Stephen Gilchrist: We are seeing the dial shift in some of the things that you mentioned but I think we know we still have to be vigilant with institutional ethics and institutional cultures. This show is called OCCURRENT AFFAIR and many of the realities that you raise in the show are decades old, but some are depressingly current. How do we address this kind of arrested development in the nation-state, but also how do you not have arrested development with your own artistic practice as well? You’re wanting to develop and stretch yourself, but there’s this tension between setting the agenda and being reactive to what Australia puts out.

Megan Cope: I think that, with the new membership as well, perhaps we’re less reactive at the moment than we once were. The fight has changed, the kind of tactics we need to apply to our practice and our language has changed somewhat. And I think that must reflect what’s going on in society as well because that’s what our works are like, as Gordon says, a mirror to the society and the space that we share. Maybe we’ll just keep doing this until we get our land back. Maybe we’ll just keep going and going and going and then once that happens, things will change fundamentally. We’ve got to dream.

“I like the old adage, “Think globally, act locally.” Most members of proppaNOW have an international profile, so we’ve had to position ourselves internationally to get recognised locally.”

Stephen Gilchrist: What are some of the current issues keeping you all up and informing your practice?

Megan Cope: My work is absolutely about Country and the state of our country. And you can see that in the works inside the gallery, where I imagine that we are the actual owners of our Country and we have the right to assess our Country and we’re the landlords and we’ve issued a condition report. I’ve done a condition report and recorded the settlers’ arrival and their recordings of abundance and the state of our Country, Quandamooka Country. And then I’ve listed damaged, undamaged and catastrophic events that have affected our Country. And I did that because my Country is very touristic and people think it’s pristine and perfect and beautiful, but actually it’s been extracted for a very, very long time. So that’s what motivated that work. The eviction notice definitely is due, my Country’s very damaged.

Stephen Gilchrist: Gordon, what about you? What’s motivating your work at the moment?

Gordon Hookey: I like the old adage, “Think globally, act locally.” Most members of proppaNOW have an international profile, so we’ve had to position ourselves internationally to get recognised locally. This country is forever looking overseas for guidance or inspiration, yet, I’m saying nothing because it’s been repeated over and over again, the true inspiration really lies in here, but we have to go outside of the country in order to be seen. So, with me at the moment, what my work is about is looking at the world and what’s going on in the world, because, like I said, we have a tendency to follow what’s going on. I refer to Australia as “Aust Trail Ya” because we’re always trailing, particularly in regard to humanity.

Lily Eather: I think Indigenous art in this country is still undervalued and underappreciated, so as aspirations for curating, I think it’s really important just to create a space for artists like these guys so they can have self-determination, decolonise audiences and yeah, look globally, think locally.

Warraba Weatherall: A lot of things are influencing my thoughts and where my energy’s going, but I don’t want to also let it go there. Obviously, there’s a shit show going on with The Voice and all these other things, and I think some of those things aren’t always productive for all our time and energy to get consumed into something like that. There’s a lot of different things happening that may or may not be conducive to what our collective aspirations are, and I think that’s really tricky to navigate. And, again, it’s just time and time again there’s someone else determining what our futures are going to be.

So, I’m interested in having some of those more localised conversations around particularly my country around Kilroy, but also I live in Brisbane, I live off Country, so what are some of those other things that we share and what are we building towards?

My particular interest is really interrogating language, the power of language. Most of us speak predominantly English all the time. We get desensitised to meanings, to sounds and context, and I feel it’s very important to critique those things and understand the different power dynamics. Even just having a dominant language, it’s the decade of Indigenous languages, so regenerating our languages and the knowledge systems that go with that. Even as artists talking about visual languages and cultural semiotics, there’s so many things we can speak about and redevelop and reposition our own terms of reference, rather than it just being Western-centric.

Tony Albert: It’s really interesting, 20 years on, to look at work about Country and the integral link that now has with climate, and that we will see climate refugees probably in our lifetime. We are aware of the situation with political refugees, and we’ve seen that happen, but not climate. The interesting thing is, Indigenous people as the oldest living, surviving culture on the world, we have dealt with climate refugees in our past, and those have been negotiated over long terms.

It’s a very difficult conversation to have, and something I’ve been researching, but it has happened here. I think the invisibility of some of the voices within those conversations, even just climate alone without looking at climate refugees, the answers to those problems have been practiced here for hundreds of thousands of years. But for me, I think it’s intrinsically important to look at the moment all throughout Australia, how those ideas of country are so deeply attached to climate.

Stephen Gilchrist: Gordon, I’m remembering when I used to work at the National Gallery of Victoria, we had your work Sacred nation, scared nation, indoctrination, and there was a big image of the globe with the words extinct written on it. This was painted and acquired in 2003, and I used to have to field a lot of complaints about this particular work of yours. I was just thinking, do you set out to make art that gets onto people’s skin? And what is the value for all of you?

Gordon Hookey: I think it’s that we’re brutally honest with ourselves. And what we represent is the world, how we see it through our eyes, through our blackfella eyes, that is different to each other. What our art does, and I’m speaking for myself here, we do hold that mirror up to society and culture and the viewer brings their own socialisation to viewing the pictures that we do.

They look at our pictures through the eyes of where they’re coming from, and you’re allowed to interpret and represent what you see. We can’t say it’s not there if you see it, but at the same time, often with my particular work, the work you talked about is loaded with poetics, metaphors and similes. So often [conservative commentators] will look at the work and they will interpret it, and then they will blame me for their interpretation. Yet it goes back to that mirror, they look at the mirror, they see themselves, and a lot of times they do not like what they see.

“I’m thinking Gordon about some of your David and Goliath victorious Aboriginal people in your paintings. There’s something about stepping into your political, cultural ancestral powers for Aboriginal people, and your muscly kangaroos, about accessing forms of power that I think is really interesting.”

Stephen Gilchrist: You had a knowing chuckle there Megan, you’ve experienced this processing of uncomfortable feelings for people?

Megan Cope: Definitely. But also, I think we grow up being told by our elders that one of the fundamental things in our culture is we have to look after the place and we have to look after each other. So really, we just try and make work that echoes that and calls people to account and holds the colony to account. And we’re not the only people that feel like that, you don’t have to be Indigenous to know what’s right and wrong when it comes to looking after Country. But I remember seeing that painting [of Gordon’s], that was my first year of uni, down south in at the Koori Institute of Education, and it just got me so fired up, it was so amazing to see this work in the NGV. It gave me permission to just keep going, you know? It was so good.

Stephen Gilchrist: I loved that all the art students would come to the NGV and they’d really get a kick out of it. But what I really loved about the work is that it got under the skin of government, and what that told me is that art isn’t impotent, art can be powerful. And I was just wondering to all of you, what is it about being an artist that can make you feel powerful?

Megan Cope: Gosh, I often don’t feel powerful, it’s terrifying, actually. The fear and anxiety to speak the truth is really hard. A lot of these things, if it was a white man saying it, it’d be different, right? It’d be totally different. It’s not that what we’re saying is really controversial, I don’t think, it’s just the truth.

Stephen Gilchrist: I’m thinking Gordon about some of your David and Goliath victorious Aboriginal people in your paintings. There’s something about stepping into your political, cultural ancestral powers for Aboriginal people, and your muscly kangaroos, about accessing forms of power that I think is really interesting.

Gordon Hookey: Well, I think what really prompted that quite early, I might have even been a student as well, but I did see a beautiful work of art, made by an artist that I admire, and the work was called Black Dog, White Dog. And it was a small drawing or painting and it was of a black dog getting its throat ripped out and beaten up by a white dog. In itself, it told of the brutality that was happening in our Country, in our lands, in our nations. But at the same time, looking at that work, it did not make me feel good. And I had to reassess that particular work. And I’m like, if I am gonna do that work, I will have the black dog beating up the white dog.

So, I made a point that if I do a work of art, a picture, a painting, or whatever it is, and I look at it and it makes me feel less than what I actually am, then that work will never leave the studio, or I would never, ever do that work.

Stephen Gilchrist: Tony, what about you? In the last couple of days, you have shown such generosity to art students, and you have a deep belief in the power of art and education.

Tony Albert: There’s just no better way of understanding anyone’s life or what they’ve been through than by actually being with them, and that’s a great privilege I’ve had the opportunity to do. And within that there’s a certain responsibility to the community, to old people, to young people, and it’s something I love to do, so it’s been a joy to be able to travel, but to also make sure that within that there’s opportunity to give back to the community.

There is no book or legislation, even within the expertise of advocacy, for visual art. So, if we’re writing the book about that, let’s try to do it right from the start, and the old ‘practice what you preach’ or ‘put your best foot forward’, all those cliches, we are responsible for that. And as we’ve seen in the last 20 years now, it’s not just our work, but it’s our philosophy, and it’s the academia that is attached to this group that is now being studied and looked at. We’ve seen things that start wrong all the time, so we’ve tried to lead with our best foot forward, that’s what I’ve always tried to do, and that is through a lot of compassion and generosity.

Stephen Gilchrist: Being part of the collective, does that help you stay the course? Does it help you be invigorated by the challenges we’re still having to face?

Megan Cope: I think we need to acknowledge the exceptional leadership that is in the collective in the senior membership, in particular Lily’s father, Uncle Laurie Nilsen. And I think one thing that’s really defined us all is the culture that has been created and held in Brisbane in particular, through the leadership of Jennifer Herd and Laurie Nilsen, through the course [Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art degree], this intergenerational culture that’s been propagated through Griffith University.

We’ve all been privy to this, and it’s been formalised through the education through that course, but also outside in the community, in the studio. So all this kind of stuff, the protocols, the way to be proper, the way to care for each other, the way to care for others, the way to be honest, the weight of that doesn’t feel heavy at all. It’s fun and exciting and we make lots of jokes about everything. And it’s a really vibrant culture that’s intergenerational at all times, that’s really important.

Stephen Gilchrist: Lily, you are currently studying art history at the moment. You trained as a nurse, and I guess art is a kind of medicine, sometimes it doesn’t taste very good. What brought you back to art history?

Lily Eather: I suppose I’ve always been surrounded by art: proppaNOW, dad [Laurie Nilsen], Fireworks Gallery in Brisbane. So, after school I went and did nursing and that’s kept me busy for eight years. And after dad passed, I did a lot of reflecting and I realised that art is a part of my identity, so something was kind of missing there. Dad always told me I wasn’t allowed to be an artist, so I had to figure out another way. That’s what made me go back to uni and I’m so glad I did, because it’s got me up here on this stage with these guys. I’m really looking forward to the future.

Gordon Hookey: It was so funny, Nanna Jen’s reaction, and me too, when you came on board, because we were saying, “Oh, we do need a nurse, all us old ones were saying that.”

Tony Albert: We’re all older and fatter!

Stephen Gilchrist: We also need art historians.

Megan Cope: I can’t remember how I found out what you [Lily] were studying, but we all were talking about it, about inviting Lily into the collective. And then we all got talking about what does that mean? It’s been an artist-only collective. So, we had some really rigorous conversations about what it means to be an art collective now, and looking at other collectives around the world like ruangrupa [in Indonesia] and others, and we realised lots of art collectives have accountants and art historians and photographers.

We were really confronted on one level about it, but then also really excited—let’s change ourselves so we can invite Lily in, and same with Warraba and Shannon who are doing their PhDs and working in the universities, not so active in their art practice but still artists. It just feels great.

“We are each other’s biggest advocates, but also each other’s biggest critics. We monitor each other; our egos, our reflection of ourselves into the world is all checked and put into play.”

Stephen Gilchrist: Vernon Ah Kee has often said that there’s a lack of critique around Aboriginal art, and he’s mentioned this in interviews with [ABC broadcaster] Daniel Browning. Within the collective, have there been conversations about trying to create definitional categories or a conceptual framework to discuss your work? Are you interested in what that discourse might be?

Tony Albert: Well, we were just doing it. That’s what was so important about us being together. And originally, we were sharing those spaces, we were critiquing each other’s work while we were making it because we’re sitting next to each other. And we came generationally from a point in time where artists were the ones working inside the institutions. And it wasn’t until people like yourself, Stephen, who came through, you gave us great hope and insight into the fact that there were Aboriginal people going through university studying art, or to do the roles that you were doing. And I’ll give credit to Hetti Perkins, Djon Mundine, Brenda Croft, Destiny Deacon, all those people inside those institutions. Artists were taking up those roles because there was no one else.

And now young Aboriginal academics are coming through because of institutional change, and I would like to hope through people like us. I do a lot of creative pathway programming, and it’s so easy to tell Aboriginal kids to get a trade but there’s so much opportunity within art, in all its facets and all its areas, and there is a need for it. That creative input is so ingrained within who we are as people as well, but you are right, there is a lack of true critique of Aboriginal art.

We are each other’s biggest advocates, but also each other’s biggest critics. We monitor each other; our egos, our reflection of ourselves into the world is all checked and put into play. That was a really huge part of what we did, and it’s such a great way of working because we share and discuss everything we’re doing, like, “Oh my God, have you read this book? Have you seen this movie? I was investigating that not so long ago, here’s all my research.”

There’s an element of disclosure within the world that we belong to, and it is for us the only way to operate, reprogramming and rethinking the way in which you do a lot of things as an artist. The best thing about the collective is pushing each other up and validating each other.

Stephen Gilchrist: How did this culture of critique help your artistic development as part of this collective? It sounded very caring and compassionate, but I imagine there were moments of bluntness as well.

Tony Albert: I don’t want to make it sound all really lovely because Gordon [Hookey], Vernon [Ah Kee] and Richard [Bell] were always really mean to me. [Laughter]

Stephen Gilchrist: But was it a strategy to toughen you younger artists up, or was it about maintaining a proppaNOW message or politic or tone?

Megan Cope: It’s about accountability. It’s about we’re accountable to each other because we’re not aspiring to mediocrity or the mediocrity that’s in Australian art, we want to be the best and we want to be honest about what’s going on here. And we have high expectations, as Tony said, about what that is. And so with that comes honesty and things that you might not want to hear, but because we are friends and because there is love, you take it on board and that’s just what family is, that’s what our communities are like. It’s not like a frightening space for anyone, I don’t think. I love it, I think it’s fantastic. We have to be challenged, right?

Gordon Hookey: Yeah. Well, the cliche was as artists within proppaNOW, if you can run the gauntlet of proppaNOW, because Richard, Vern and Uncle Loz can be very cruel in regards to critique of work, so if we can run the gauntlet of each other, then everything that happens outside of proppaNOW is kind of like water off a duck’s back, you know?

It’s quite tame because my peers, my contemporaries here aren’t afraid to tell you if your work is shit, and they’ll say it, and then we will maybe fight back a little bit. But in the end, the brutal honesty between us and our work and what we do will prevail.

And what you alluded to, about Vern [Vernon Ah Kee] saying there’s no real critical acclaim happening with the work we do, it’s simply because perhaps people are afraid, the white writers and theorists and historians perhaps are afraid of being labelled racist, or whatever.

Megan Cope: It really comes back to what it’s like to grow up in community as blackfellas. The process of self-determination requires an intellectual process where you have to question everything, right? So that’s fundamental. And that then applies to what you discover when you question everything. A lot of people don’t do that, but we can all do that if we want to be creating the world that we want live in. We have to do that.

Stephen Gilchrist: If you weren’t seeing a deep enough critique of your own work, presumably the collective helped you design your own systems of value, what you saw as a measure of success and for you individually, but also as a collective, what were those measures of success? What does success mean to you?

Megan Cope: Ten years ago, when I didn’t have the courage to say things on my own, whenever we would have a proppaNOW show, I’d put those works in because the collective could be a bit of a shield for me. And whilst we talk about critique, on the other side of that we support each other, so that was really amazing, and built up a lot of courage over the last 10 years and a lot of strength. And I think my work has become much better as a result of that.

Lily Eather: I suppose I can speak about my dad’s work. When you were talking about accountability, I felt like I absorbed that as a kid and not just dad, everyone in proppaNOW challenges prescribed notions of what Aboriginal art is. And as a kid, I was defending his work as Aboriginal art, so that’s funny for a little kid to absorb that power he had.

Warraba Weatherall: It’s really special to be part of proppaNOW. I’ve idolised these fellas for a long time, they’ve been formally or informally my mentors for a long time. But I think the conversations we have and the work we make and the things we’re actively doing within the community, there’s so many things that need addressing and to have conversations about that there’s unfortunately no limit of things to actually do. But the importance of just being a part of those conversations, and having some of those really hard conversations, is just a natural way to work through that stuff.

And sometimes we don’t have an answer of what is the best thing, but by that yarning and finding a loose consensus, there’s a way to approach it. And I think having that awareness, but also that vulnerability to sometimes say, “Well, I don’t know, this is the first time we’ve had to try to decolonise something, so then how are we going to navigate that?” And I think that’s really important. But there’s no lack of things to aspire to or do, just keep chipping away, and hopefully the rest of the country jumps on board quicker.

Gordon Hookey: For me, I think the notion of success or what I aspire to, it continually changes throughout your career or wherever you’re at. I think I’ve been making art now solidly for about 35 to 40 years, and it’s the fact that I’ve continued my practice despite everything. I used to gauge when I was a student or packing my CV with trying to win that art prize or this art prize, then later on it was getting into this major show or getting printed in this magazine or selling this artwork or that artwork or getting into this collection—like they were kind of markers of certain success.

But in the end, as your career goes on, I look back and think, “Does that really matter?” I mean, we can do with money on the way to help us, but in the end I think a marker of success is if you can maintain your practice and keep making art despite living off an oily rag or squeezing that blood from a stone, if you can do that as an artist in a country that doesn’t really support its creative people, to me that is a remarkable indication of success because you’ve prevailed despite the odds of society and culture, and just kept going. To me, to see someone continually create without having to take on a real job to subsidise their practice, it’s a remarkable thing.

Stephen Gilchrist: It is a real job to be an artist, it takes a lot of guts. I wanted to talk about the international recognition of your work. For this exhibition [OCCURRENT AFFAIR] you [proppaNOW] were nominated and won the Jane Lombard Prize for Art and Social Justice in New York. It’s an amazing achievement, and recognises your outstanding contributions not only to art, but also social justice as well. What did that award mean to you?

Megan Cope: It’s the most important for people like Jennifer [Herd] and Uncle Laurie. He’s not with us now, but even when he became unwell we were like, “We need to have another show.” We hadn’t had an exhibition for five years. Everyone was doing their own thing and checking in here and there, some members have stronger relationships with other members within the group. And I was just really, really determined to have a show and for an institution to take it because we hadn’t had that recognition at all. And it felt urgent with Uncle Laurie being unwell. So we really talked quite tough about it. Some members were saying, “Oh well, if Australia doesn’t get it, it gets what it deserves.”

But I thought as a younger person in the collective, no, we’ve got to give it a shot at least. And I’m so glad because this exhibition won the award from the Vera List Centre for Art and Politics in New York City. It’s really wonderful for our old people and for us to be able to go over there and talk about this with other communities, and to connect with the world because this country does like to import culture and ideas and its largest export is Aboriginal art, though not the kind that we make. It’s great, it put a fire under us again.

Gordon Hookey: I can agree with that. Because most of the artists—Richard, Vern, Tony, Megs—do have different levels of achievement internationally, their profile is quite high in a lot of the nations and countries, but like we were saying before, Australia has failed to recognise the achievement of individuals, but then as a group it was so easy to marry their achievements together as that collective.

When I look at the names of those at the Lombard Foundation and in the committees, these are all people that our members have crossed paths with, so they were familiar with First Nations struggles throughout the world, and they were able to identify our struggles here, there was no explaining at all. It was only logical for them that we’d be recipient for a major ward with not only individual achievement but collective achievement as a group together.

Because when you look at it for 20 years, we have been banging our heads against the wall in this country with our concerns and our issues, only to not be heard. So then to have a major award bestowed upon us, I was kinda like, “Oh, okay” initially, and then there was all this contact with people overseas, questions, they wanted videos, they wanted us talking about things.

It was just like a matter of fact to me, and then I saw this article in The Guardianabout us, little old us, winning this award. And the writer wrote something to the effect that in the US civil rights movements, African Americans see themselves as the leaders of politics and change and all that, and then it went on to say this little group in Brisbane could go a long way to galvanising themselves over there. And I’m like, what are they talking about? You know?

But then, after thinking about it and looking at what was written and what they were saying, I guess the gravitas of this award became a little bit more apparent. I won’t know until I’m there, but in the past, as Tony was saying in previous meetings, the award was offered to individuals. And—how much was it? $40,000 US, and a Yoko Ono print. We have to divide that up eight times and get the scissors out. [Laughter]

“There’s a norm within Australia that is really polarised. Like if you are critical of an institution, then you are anti-institutional; if you are critical of a dominating power of white Australia, then you are anti-white.”

Megan Cope: But one of the things that also is part of the collective is being humble, and it was really a little bit confronting, the recognition, and it made us a little bit uncomfortable. It’s like this award held a mirror up to us, but I think in the best possible way, because it’s made us realise that we’re 20 years old, we need to develop an archive, we need renewal in the collective—all of this recognition has really brought a lot of change in the collective, but in a really great way so that we can continue.

Stephen Gilchrist: And having those conversations about the necessity of an institutional show. Your work has always been about institutional critique, so what were the conversations that you had about how the power dynamics have changed within institutions? What are the differing terms of reference for you to feel comfortable to not be over-determined by that institutional space?

Megan Cope: Those conversations haven’t really happened, but we were accused of being anti-institutional, and in our Yarn Event that’s in the catalogue—Yarn Event, I dunno if anyone gets it because it’s OCCURRENT AFFAIR, pretty clever, that was me by the way [laughter]. We were never anti-institutional, we just want to make a better world, and we want space and we want to be included. That’s our culture. This is our country.

Gordon Hookey: Our members are lecturers and teachers and even professors at universities, and over the course of my time as an artist and looking at my fellow contemporaries, they’re always travelling around doing guest lectures. We’re always on panels. We’re always educating people by talking as well as with our art. Our work has been intellectualised anyway by the mere fact that we’re preaching to you. Most of the time we’re preaching to the converted anyway, but at least it’s being said. And with OCCURRENT AFFAIR, the fact that a university took it on and at the opening and all the events thereafter, the students at the University [of Queensland], they owned it and created their own little program related to the art.

And then the next venue happens to be Curtin University, and then the venue after that is here [at NAS]. They are places of higher learning. So, any critique about being elitist or anti-institutional is based on a fallacy because we are right there within them. In a nutshell, every blackfella, we are positioned at that interface where cultures converge and meet in the greater scheme of knowledge. So in effect we’re all primary source material as far as learning and education goes, and people need to value that space and value us as First Nations people in this country, but also First Nations people in all the other nations as well, that have had to negotiate or repel invasion of who we are.

“It’s really important to find the spiritual, cultural and physical space to get together and start with that.”

Warraba Weatherall: There’s a norm within Australia that is really polarised. Like if you are critical of an institution, then you are anti-institutional; if you are critical of a dominating power of white Australia, then you are anti-white. But there needs to be an understanding that people can be critical of something and have that rigour behind that conversation, and then still have love and still get on with it. It doesn’t mean that you are always in contempt or oppositional, but like they were saying, we’ve had knowledge systems in this country for so long. If we really look at the institutions, they were set up for western epistemology and knowledge systems, as a venue to prioritise and privilege them. That’s the setup up of those institutions.

Audience question: There’s a few of us countrymen here listening and talking to you, probably inspired by you and have been for a long time. What advice would you give countrymen who are thinking about potentially starting their own collective for their own needs today?

Gordon Hookey: All we were is just a group of friends, a group of mates who used to hang out and pay one another out, and talk shit to one another and just have fun. We’re just a group of artists that are talking, and it just so happens a name gets put on us. Well, we put the name on it ourselves, but a start would be is when you see a groups of artists just hanging out together all the time who value each other’s company as friends, that could be a genesis to build on. And it took us such a long time to even formalise our existence because we weren’t structured in any way, it happened that we somehow ended up in a space together and just continued what we were doing and become proppaNOW the collective.

But it’s more than that because like I was saying earlier we’ve become more or less an art movement, a way of thinking, an attitude, with a strong sense of who we are.

Megan Cope: It’s really important to find the spiritual, cultural and physical space to get together and start with that.

Lily Eather: And think about longevity, really aim for being there for the long haul.

Gordon Hookey: It’s kinda like a cult, like the Eagles said, “You can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave.” [Laughter]

OCCURRENT AFFAIR

University of Sunshine Coast Art Gallery

24 February – 4 May 2024

OCCURRENT AFFAIR then continues touring NSW and Queensland into 2024.

This article is a shortened and edited version of a panel discussion featuring members of proppaNOW, hosted by the National Art School, 24 July 2023.