Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In the Great Chain of Being, a medieval Neoplatonic conception of the world, all matter is arranged hierarchically with plants right at the bottom, just above rocks, and man not far from the top. Even today, as we come to understand ecosystems as entwined networks – and despite advances in Western science which, for example, have revealed the complex ways that plants communicate – this idea still holds sway. But for millennia, Aboriginal Australians have held a different worldview in which plants are seen as kin; not as insentient matter subordinate to humans.

“Rock, tree, river, hill, animal, human – all were formed of the same substance by the Ancestors who continue to live in land, water, sky. Country is filled with relations speaking language and following Law, no matter whether the shape of that relation is human, rock, crow, wattle,” explained Ambelin Kwaymullina in her 2005 essay, ‘Seeing the Light: Aboriginal Law, Learning and Sustainable Living in Country.’ In the group show Solidarity: Inscriptions for the future, three women, Winsome Jobling, Djirrirra Wununmurra and Mulkun Wirrpanda, presented drawings, collages, prints and bark paintings which relied on a deep understanding of our complex relationships with plants.

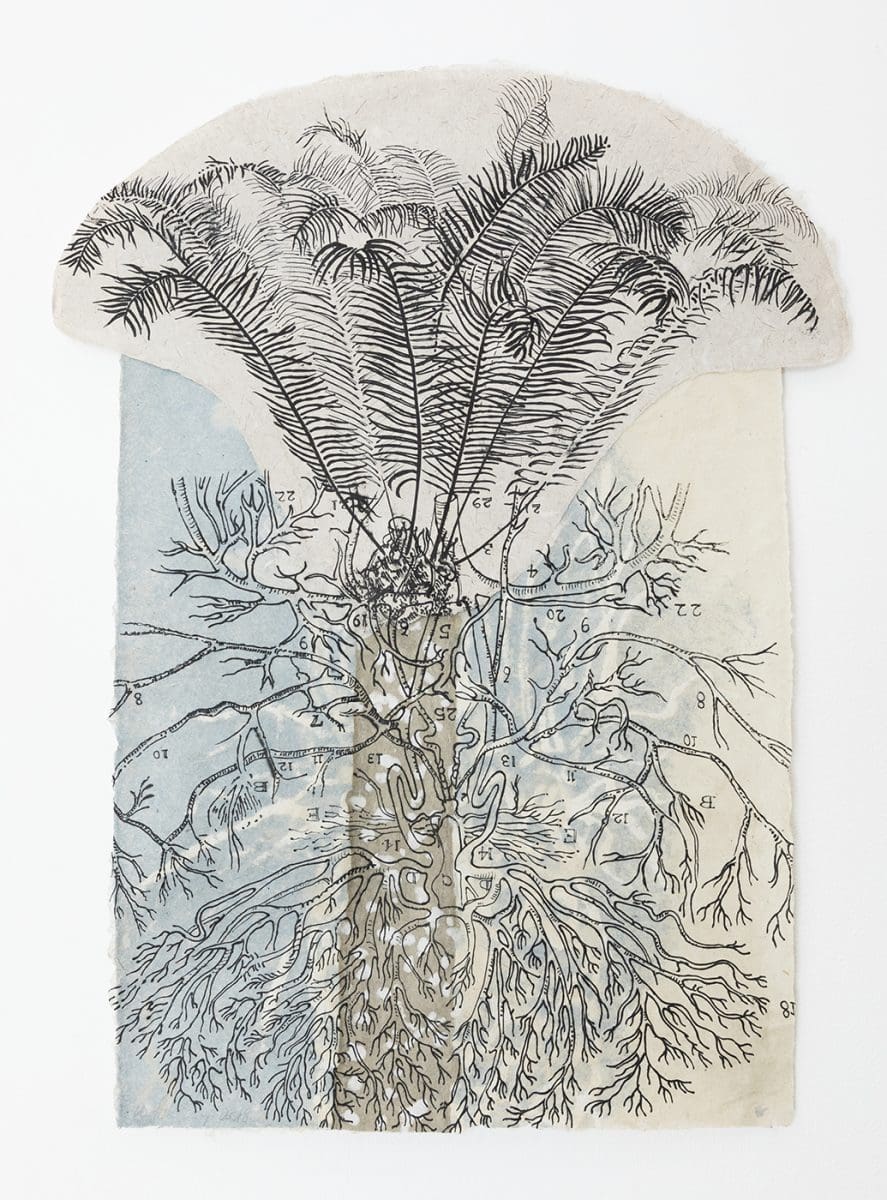

Winsome Jobling, the only non-Indigenous artist in the trio, makes her own paper onto which she prints images of plants. These are then literally stitched together into layered collages. Jobling gathers natural pigments and fibres for her work from a patch of bush near her home in Darwin, a piece of land which she also helps to regenerate with native shrubs, trees and grasses. She incorporates both native and introduced plant species in her handmade papers, including invasive Gamba grass which is threatening the land she works on.

The tendrils and roots of the plants in Jobling’s mixed-media works on paper resemble cardiovascular networks of veins as depicted in delicate etchings by the 16th-century anatomist Andreas Vesalius. In this way, Jobling taps into Western aesthetic and scientific traditions, while also pointing to an understanding of the interconnectedness of all life on Earth.

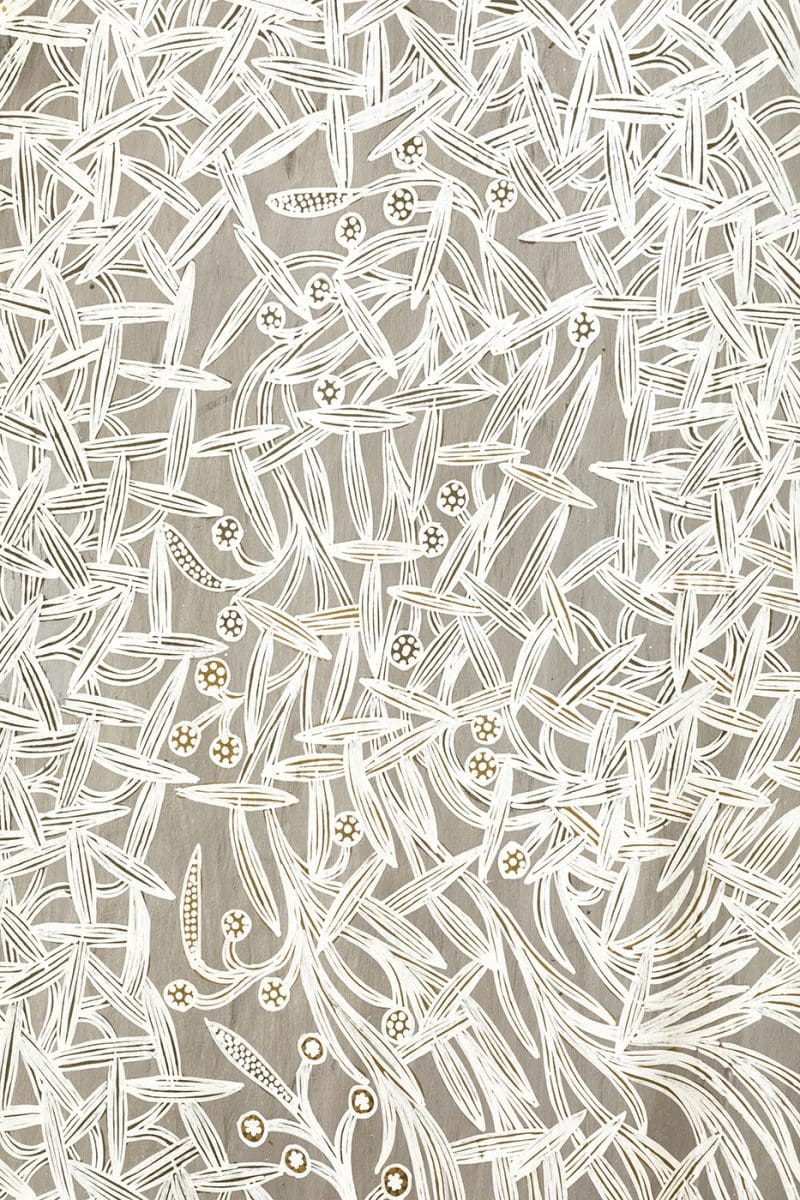

In Solidarity, all of Djirrirra Wununmurra’s bark paintings (from 2017 and 2018) were titled Yukuwa. A Yolŋu artist from East Arnhem Land, Wununmurra is also known as Yukuwa, which means yam in her language, so her detailed bark paintings are a kind of self-portrait as well as a celebration of culture, ceremony and Country. In 2012, her unique yam motif won her the bark painting prize in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA).

Many Aboriginal motifs appear to be abstract, at least to untrained Western eyes, but Wununmurra’s yams are instantly recognisable as plants. In her incredibly dynamic spiralling compositions the shapes of leaves are clearly discernible, as are clusters of flowers laden with seeds.

Using natural ochres on bark, one of Wununmurra’s Yukuwa paintings is a masterclass in the use of negative space. From a distance it appeared that the artist had incised her design through white ochre, but closer inspection revealed that she had patiently painted all of the gaps around her design, leaving just thin slivers of under-painted bark to delineate her swirling plant forms.

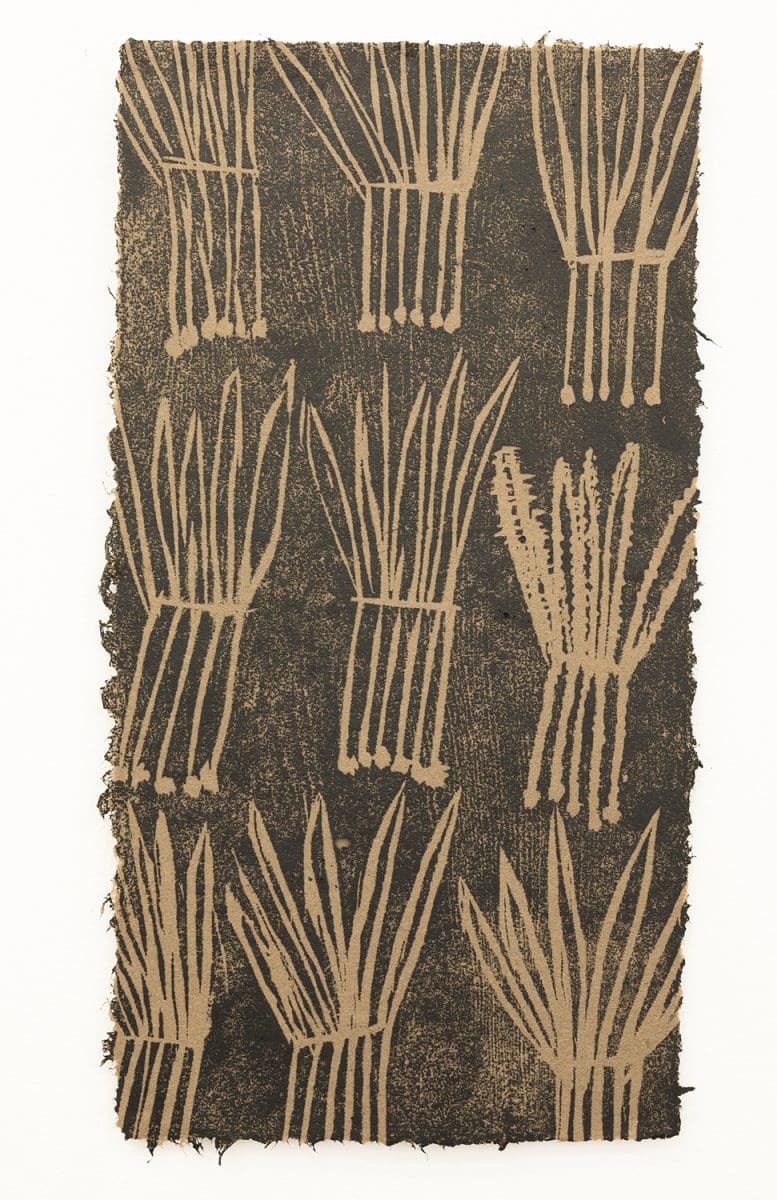

The third artist, Mulkun Wirrpanda is a respected Elder of the Dhudi-Djapu clan of the Dhuwa moiety who reside in an intertidal zone in north-east Arnhem Land. She is well known for her bark paintings and painted sculptures depicting traditional edible plants. Midawarr | Harvest, The National Museum of Australia show which features an extensive range of her bush food paintings alongside works by John Wolseley, has been touring since 2017.

Although she is probably the best known of the three artists, in Solidarity: Inscriptions for the future, Wirrpanda was represented by just three artworks depicting two plants. In her diptych of etchings, both titled Rakay, 2018, and printed on stringy bark paper made for her by Jobling, Wirrpanda depicted clusters of native wild chestnuts loosely sketched. In her bark painting, Dharrangi, 2007, the artist used imagery of a freshwater plant to create a much denser and more rectilinear composition.

According to the exhibition room sheet, the word solidarity in the title was an invitation to “walk together.” Whether or not we take up this offer and recognise the deep knowledge embodied in their artworks is up to us. Artists can only do so much. But Djirrirra Wununmurra’s stunning works in particular seemed to pulsate with a barely contained energy that points to our vibrant entanglement with plants. A powerful message, hard to ignore.

Solidarity: Inscriptions for the future was on display from 22 June to 27 July at The Cross Arts Projects, Sydney.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.