Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Making and embellishing textiles used to play an important part in ordinary life. These days most people (in wealthy nations at least) buy their clothing, curtains and cushions readymade. Nevertheless, the importance of textile techniques is evident in the way that they have become part of the way we speak. We quote wise little homilies such as ‘a stitch in time saves nine,’ and we speak of the ‘fabric’ of time, or of plans ‘unravelling.’

They are a little too mired in utility, a little too (and let’s be frank here) feminine to be taken seriously by old-school patricians of the art world. But despite their crafty feminine taint (indeed, often because of it) more and more artists are adding needle and thread to their creative arsenals.

In the group exhibition Slipstitch, curator Belinda von Mengersen presented works by 12 Australian artists who make the most of the cultural associations of embroidery: Mae Finlayson, David Green, Lucas Grogan, Alice Kettle, Tim Moore, Silke Raetze, Demelza Sherwood, Matt Siwerski, Jane Theau, Sera Waters, Elyse Watkins and Ilka White. And the best works in the show either flirted with or subverted the notion that embroidery is prim and proper women’s work.

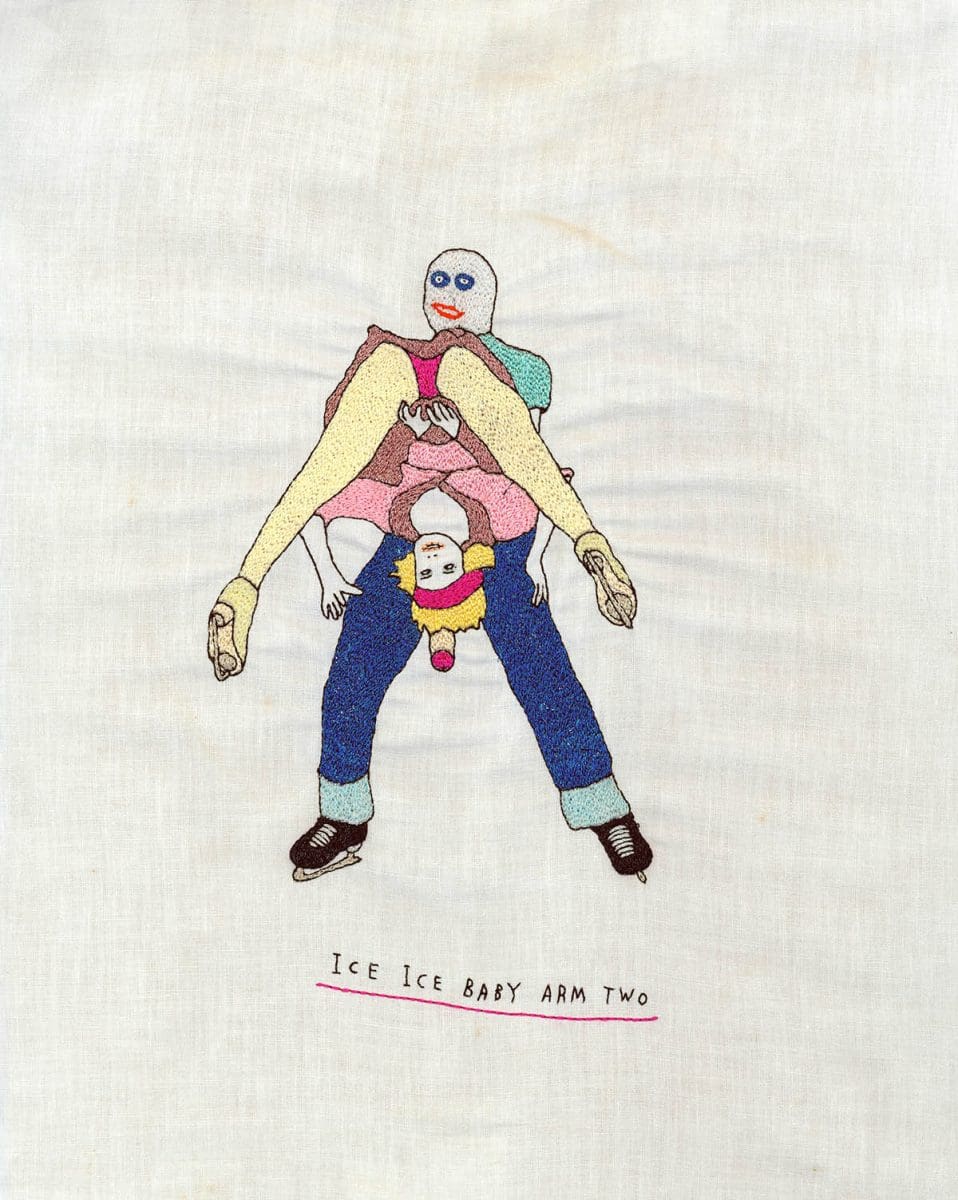

There was nothing straight-laced about Tim Moore’s work. In fact his cheeky tableaux were so downright dirty (in a good clean fun kinda way) that they necessitated a ‘beware of explicit imagery’ warning on the exhibition entrance. In Bunny Bunny Same Shoes, 2007, two slightly pudgy ladies wore matching sandals, rabbit ears and not much else. In Man Whole Summer Fruits, 2007, a nude woman with a wooden leg offered bright red raspberries to a shirtless man up to his waist in a hole.

Victorian ladies would have dissolved into blushes stitching Moore’s nude figures. His fabric was un-hemmed and stained, and his characters were definitely denizens of the demimonde. But, strangely, his images were neither lewd nor crude. Something about the juxtaposition of Moore’s very precise stitching with his kinky subject matter rendered his images funny rather than titillating. The fastidious, lady-like technique of embroidery allowed the artist to sidestep pornography in favour of humour.

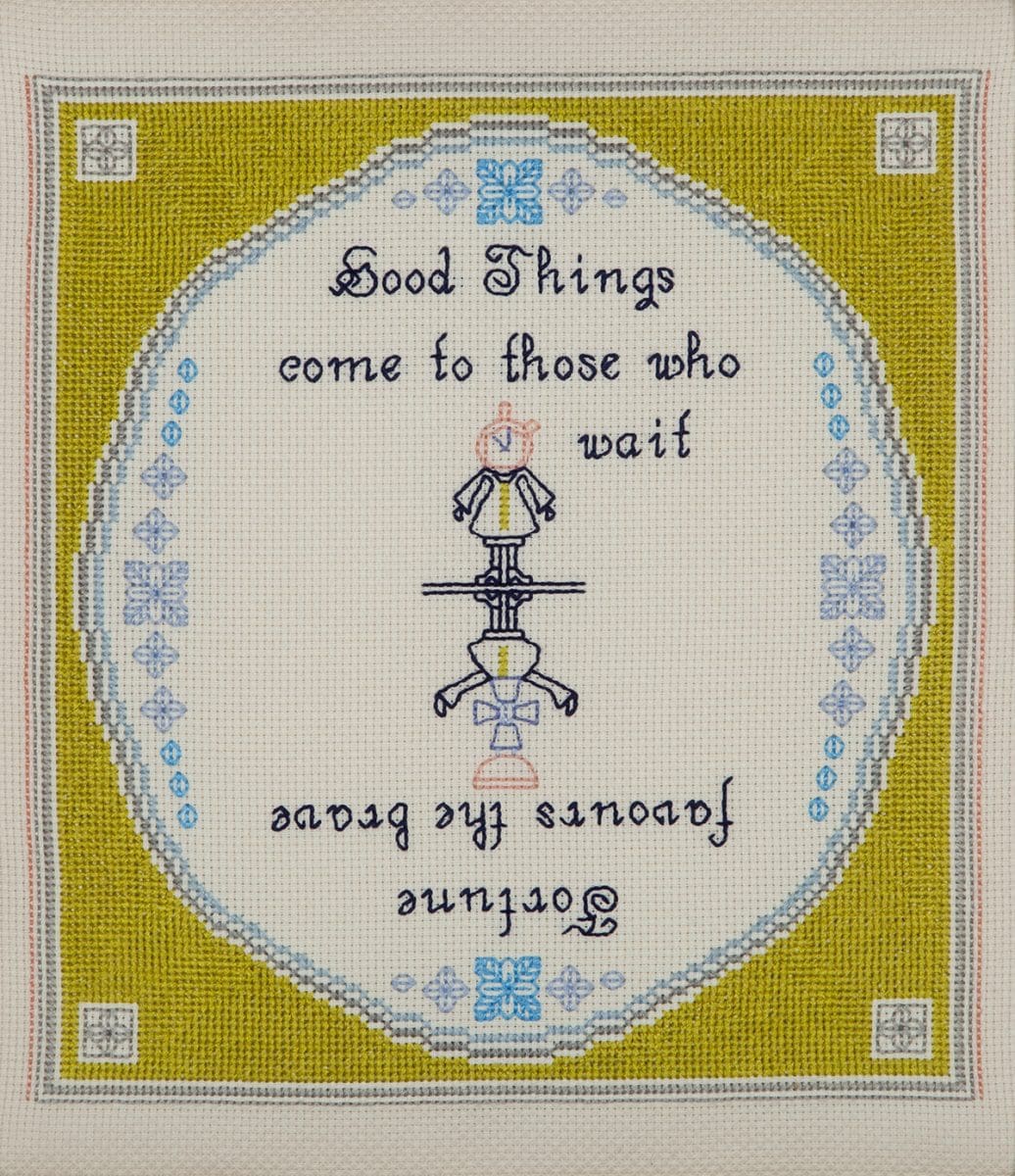

Silke Raetze also made a virtue of the erstwhile reputation of embroidery as a gender-specific arbiter of morals. Cross-stitched samplers emblazoned with wholesome homilies or biblical texts were a traditional feminine rite of passage. In her work, Raetze puts a contemporary spin on this embroidery form. On her beautifully stitched samplers she wrote things like ‘One day I forgot to be pretty.’ They seemed innocuous at a distance, but close-up it was clear that Raetze had stitched irony, and a cutting critique of our current culture and the choices women can and cannot make, right into the fabric of her work.

And both Demelza Sherwood and Matt Siwerski used this conundrum to their advantage in Slipstitch.

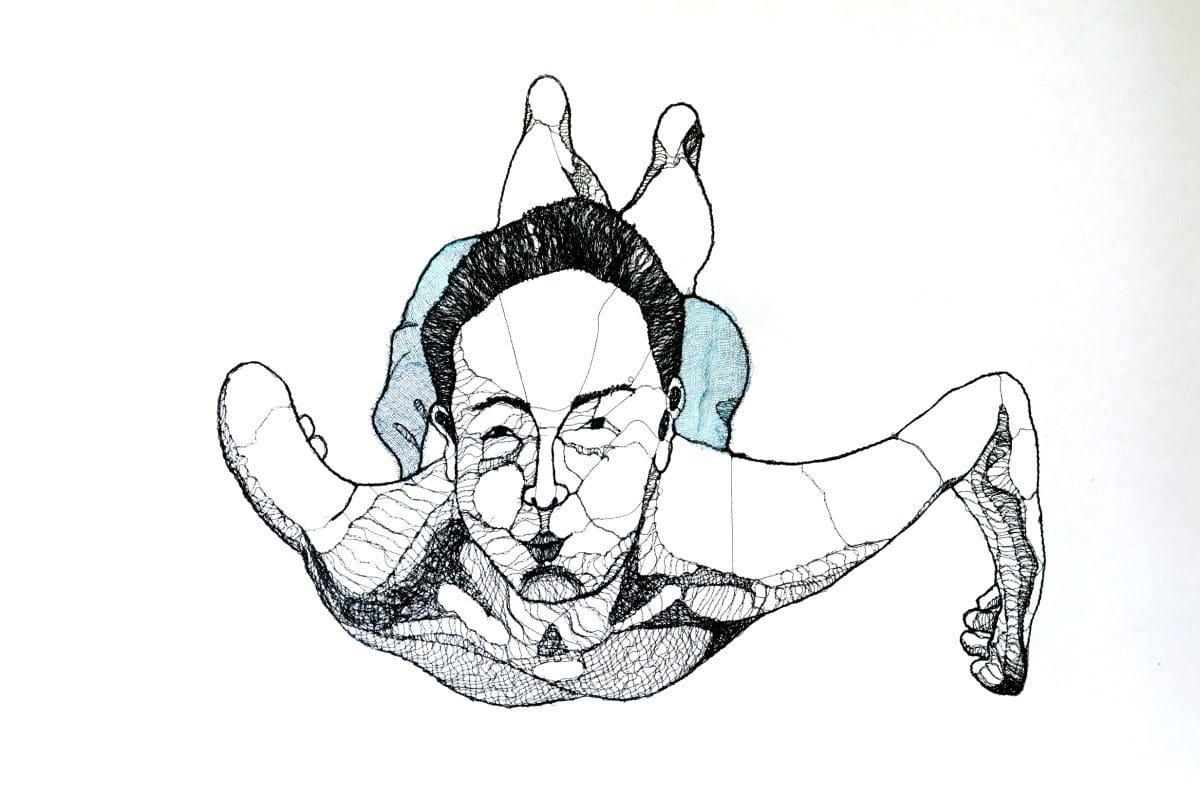

While Moore and Raetze displayed their technical prowess, Sherwood’s work was deliberately, defiantly messy. Her stitches were ragged, uneven and rough, threads dangled provocatively. Sherwood used embroidery to create works that resembled sketches, she somehow managed to translate the loose, swift immediacy of drawing to this much more laborious technique. And by presenting her rough thread sketches on vintage linen doilies which were already decorated with embroidery and tatting, fine examples of traditional women’s work, Sherwood made it abundantly clear that she refuses to be constrained by the clichéd norms of gender.

Matt Siwerski made much the same point, albeit from a male perspective, in his Self-portrait series, 2014. Using rough black thread on tough, dirty woven polypropylene bags, the self was actually absent in Siwerski’s self-portraits. Instead he presented portraits of a shirt, a hoodie and a T-shirt with a pair of pants and braces: illustrations of that old adage ‘clothes make the man’ and a nod to Judith Butler’s influential theory that gender is a kind of performance in which dressing-up plays a key role.

In Slipstitch, many of the artists creatively exploited the stereotypically feminine associations inherent in embroidery. As a medium, its power seems to come in large part from its marginalised position. Perhaps we should thank those stuffy patricians for manning the art/craft barricades so stalwartly.

Slipstitch was at Mosman Art Gallery, Sydney, from 3 December, 2016 to 29 January. This a NETS Victoria touring exhibition, originally developed by Ararat Gallery. Its next stop will be Tweed Regional Gallery from 3 March to 18 June.