Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Covering the entire body, skin is not only the largest human organ but also the very basis for observing external appearance. From anatomical illustrations to Renaissance masterpieces, representations of skin and flesh occur throughout history. Via the work of contemporary Australian artists, a new exhibition at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, Skin Thing peels back the facade and triggers a 21st century conversation about skin’s association with issues of race, gender, health and politics.

After “thinking intensely” about the relationship between art and textiles, O’Neill became aware of “the curious interchangeability between clothing and skin; the way that clothing is made to mimic skin, or the way that it absorbs the smell of the body”. Skin Thing’s title is adopted from the skin trader’s business name.

Some Australian artists are comfortably linked with the depiction of flesh – think Patricia Piccinini, Mike Parr and Michael Zavros for example – yet Skin Thing incorporates work from more unexpected sources and broadens the dialogue on skin’s use in a contemporary setting. It highlights work by artists Adam Geczy and Peter Sculthorpe, Polly Borland, eX de Medici, Paul Knight, Archie Moore, Stuart Ringholt, Charles Robb, Salote Tawale and Jodie Whalen, who are joined by well-known publisher, Perimeter Books. Not confined to one medium, works in the exhibition vary widely from eX de Medici’s 1989 Heads project comprising portraits of tattooed people, to Perimeter’s allied selection of art books and Ringholt’s documentation of his naked exhibition tours at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art, where guests were also required to be naked.

In several works from her Pupa series, Borland’s images include anthropomorphic forms created with the assistance of mirrors and distorted human figures photographed behind obscure glass. The fleshy physicality of the figures – occasionally injected with flashes of red – assists the viewer to counter their unreal appearance and infer a human likeness. Also captured in photographs, Knight’s folded, improvised images depict couples lying in bed. Employing people of different race, age and gender, Knight explores moments of sexual intimacy using skin as a palpable seductive ingredient.

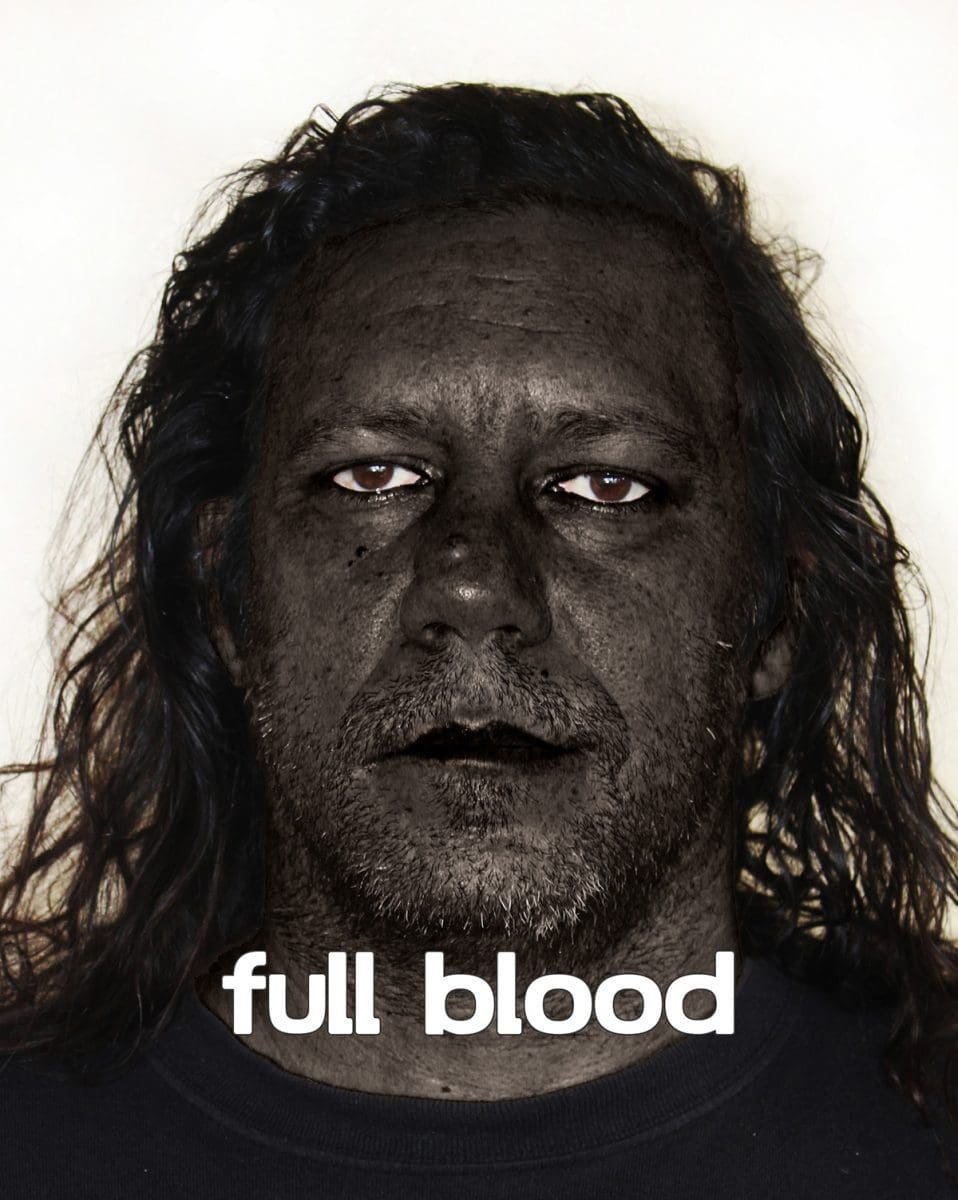

A visual manifestation of the politics of skin, Moore’s Black Fraction series of 100 selfies are each super- imposed with a Latin term that employs an historical reference to people of mixed race. Evolving in a formal scientific classification from Full Blood through to Hectoroon (white), the images are as absurd as they are deadly serious. Likewise, Tawale’s mask-like self-portrait of the artist painted with exaggerated white and red face makeup, Portrait #37 equals an about-face on blackface – a demeaning stereotype of the ‘other’ directed at people of colour. Known for employing traditional materials, other Tawale works employ the Masi (also known as the Tapa) and bark cloth made from mulberry bark to explore the artist’s blended Fijian/European heritage. As O’Neill notes, both artists “prompt us to question the aesthetics of skin colour, and the attendant historical legacies of those kinds of biases”.

Appearing abstract at a distance, Geczy’s two paintings on canvas, Fitness Paintings (Your Body Does Not Count) on closer inspection comprise vertical waves of tally marks that resemble reptilian-like armour. In contrasting shades, each painting records a pair of exercises – arm curls and sit ups; lunges and push-ups – completed over time. According to the artist, “the scope of the actions is determined by the formal parameters of the canvas dimensions and the size of the notations”.

Whalen’s new performance revisits an earlier work, Positive/Negative, Negative/Positive where she completed two physical feats – consuming the daily recommended amount of energy in a single sitting, and subsequently attempting to burn the same number of kilojoules. Transforming her body in the process of making her work, Whalen draws attention to the modern preoccupation with health, fitness and body obsession, and the extremes of its external display. Suggesting that the gym has growing spiritual significance for some, O’Neill refers to the gym as a “modern chapel of body worship”.

Skin Thing illustrates the endurance of flesh as an artistic concern and its flexibility as a signifier of sensibilities and prejudices. The show suggests that if we quit taking skin for granted, more will be revealed. O’Neill acknowledges that the show is intended to provoke dialogue about changes in the way skin is scrutinised and to question our biases, “I hope it reveals how skin might provide a window onto our complicated attitudes to race, body image and social taboos”.

Skin Thing

Bundoora Homestead Art Centre

23 June – 6 August