Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

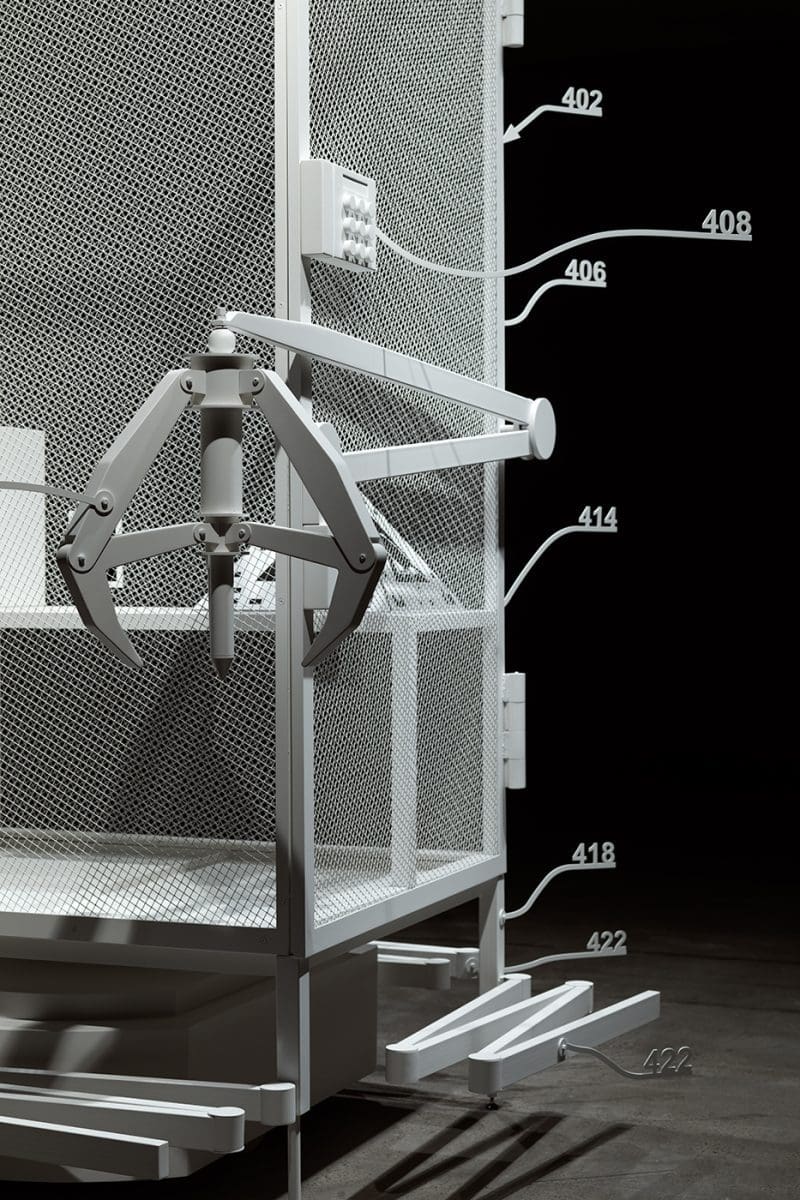

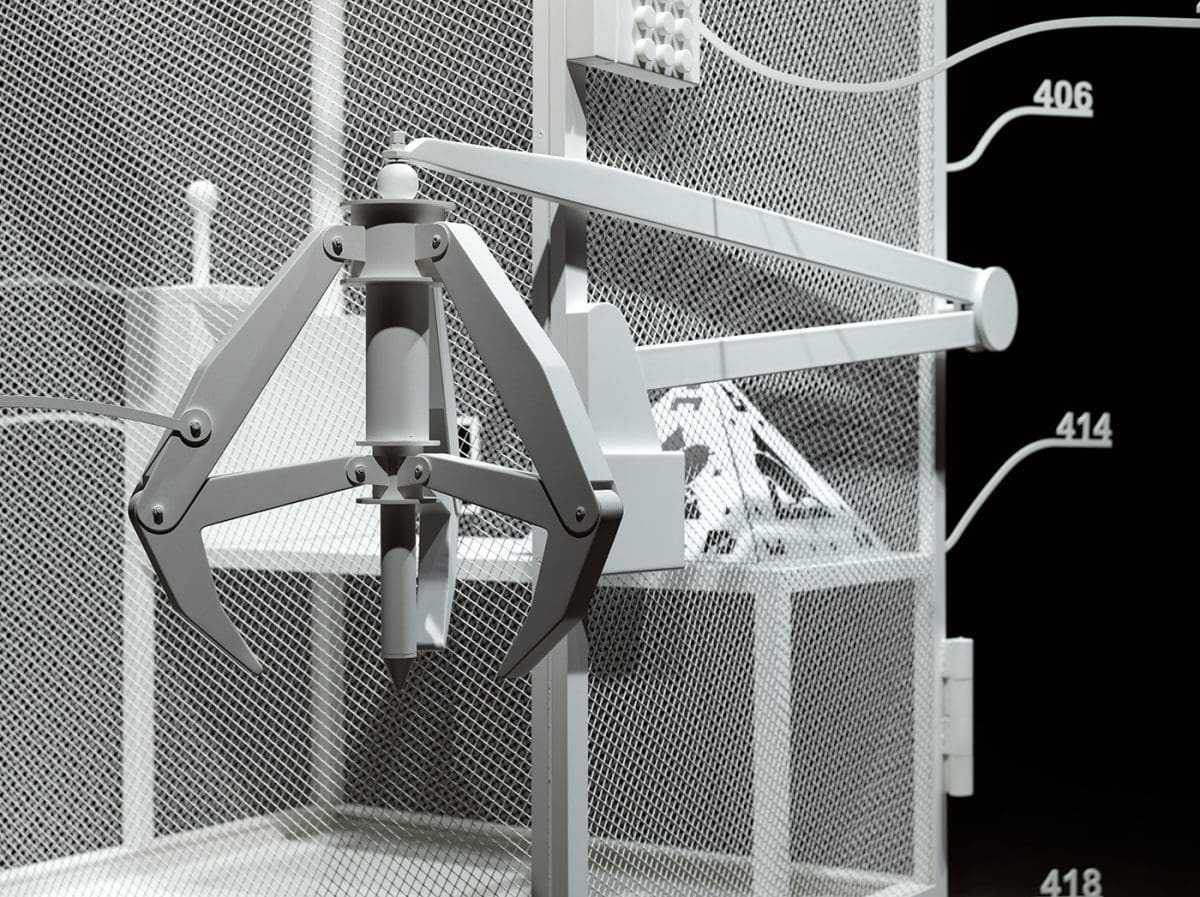

It is a matter of both awe and horror to contemplate Australia’s larger mining sites: vast wounds in the earth that are largely automated and seemingly inexorable in their gouging power. In Simon Denny’s Mine, we see multiple images of heavy machinery. We also see industry infomercials, co-opted into large cardboard displays that celebrate the extraordinary efficiency and power of these endeavours.

At the centre of this is Denny’s own board game Extractor – a scaled-up version of the classic Australian game Squatter. Another version (the scale of a real board game) is for sale inside the exhibition, complete with a rule book including exhibition essays. It’s a clever and effective ploy, designed to bring attention to our own part in the story of Earth’s resource depletion and environmental catastrophe. And in another reading of the word ‘mine’, the artist looks at humans themselves being exploited in data extraction.

Denny’s prognosis in Mine is grim: as he says, instead of farming sheep and mining the landscape, we are now concentrating on mining and monetising data, with surveillance capitalism claiming human experience as raw material for extracting, prediction and sales: “We are all losing the game and the game is faulty.”

In Mine, we are placed at the centre of this, because moving around the show means being a piece on the board. Further, we navigate the show using one of Mona’s ‘O’ devices – iPod Touch based tools generally used in the museum to replace old-fashioned wall text-panels, but in this instance, to conjure a virtual layer of augmented reality throughout Mine. As curator Emma Pike notes, Denny reveals the rare metals used to create these devices are mined as part of the economic structures the show critiques. Thus, he shows us with irony how hard it is to separate ourselves from these technologies.

Room one explores the fate of the near-extinct King Island Brown Thornbill, the ‘canary in the goldmine’; room two delivers quantities of data about the impact of mining; and in room three, figurative sculptures by other artists such as Fiona Hall, Julie Rrap, Ronnie van Hout and Patricia Piccinini are like a serenade to resource extraction work. The thematic connections between these impressive and nuanced spaces are primarily teased out by using the ‘O’ – which, as Denny points out, is of course extracting data from us for Mona. As Pike observes, “although we do this… we don’t have the computer power to process it all, let alone understand what it might be useful for in the future.”

Denny has done an extraordinary amount of research and strategically threaded it through a provocatively deployed visual experience. And while he isn’t naive about the capacity of visitors to adopt a critical distance from their handheld devices, he is also alive to how willingly we let data be extracted from us.

It is hard to know if anyone will leave these rooms feeling energised for political change, with an extinction rebellion song in their hearts: they’ll probably be too busy fiddling with their O’s or their own phones, deep in the Mona mine, carved into the sandstone.

Simon Denny, Mine, Mona, Museum of Old and New Art is on until 13 April 2020.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2019 print edition of Art Guide Australia.