Editor’s note: I can’t think of an event in the recent history that has galvanised the country’s artistic community quite like the cancellation of Khaled Sabsabi’s Venice Biennale presentation. But, to me, the initial reactions—outrage, anger— explored in countless articles and social media posts haven’t yet found the language to articulate the complex forces that have led to this moment. Or what it means not just for freedom of expression in this country, but for the art that audiences are exposed to, now and in the future. Silent Spring, a reported essay by journalist Dee Jefferson, is the first in Art Guide’s new essay series The Long View, which charts the relationship between art and the wider world and creates space for the conversations we believe will continue to shape the culture. It draws on many interviews with artists and arts workers to paint a powerful picture of the event’s long-term implications and what is at stake for art in Australia.

—Neha Kale, editor-at-large

The cancellation of Khaled Sabsabi’s presentation at Venice Biennale signals a long-simmering breakdown of trust between artists and institutions—one that risks threatening the breadth and depth of artistic expression in Australia for generations to come. Dee Jefferson reports.

When artist Khaled Sabsabi was announced as Australia’s national representative for the 2026 Venice Biennale, he told Guardian Australia he was “quite shocked”. “I felt that, in this time and in this space, this wouldn’t happen because of who I am.”

Sabsabi seemed to know or suspect that as a Muslim man born in Lebanon, who migrated to Western Sydney with his family as a child, he was somehow an unacceptable representative of Australia on the international stage.

Within less than a week, he and his collaborator, curator Michael Dagostino, had been dumped by Creative Australia, the government’s arts investment and advisory body, which administrates Australia’s presence at the Biennale. The decision was made after first The Australian newspaper and then a conservative MP spot-lit and criticised two of Sabsabi’s earlier works and suggested he was promoting terrorism.

The decision to revoke Sabsabi and Dagostino’s appointment is shocking in many ways—for being made in haste (a mere five hours after Liberal Senator Claire Chandler’s remarks during question time), and for being prompted, according to Creative Australia CEO Adrian Collette, by a politician’s assessment of an 18-second video artwork she had never seen—a work that was almost 20 years old, and nothing to do with the Venice project—by an artist whose practice she was entirely unfamiliar with.

Creative Australia’s reasoning was equally shocking: that “a prolonged and divisive debate about the 2026 selection outcome poses an unacceptable risk to public support for Australia’s artistic community”. A statement made without any consultation to assess the risk, and without giving Sabsabi a chance to speak to the board.

As a body required by its establishing legislation to “uphold and promote freedom of expression in the arts and to support Australian arts practice that reflects the diversity of Australia”, Creative Australia could reasonably have been expected to make a statement in support of Sabsabi and his art, and to advocate for his Venice Biennale project, which only six days earlier its CEO had said “reflects the diversity and plurality of Australia’s rich culture, and will spark meaningful conversations with audiences around the world”.

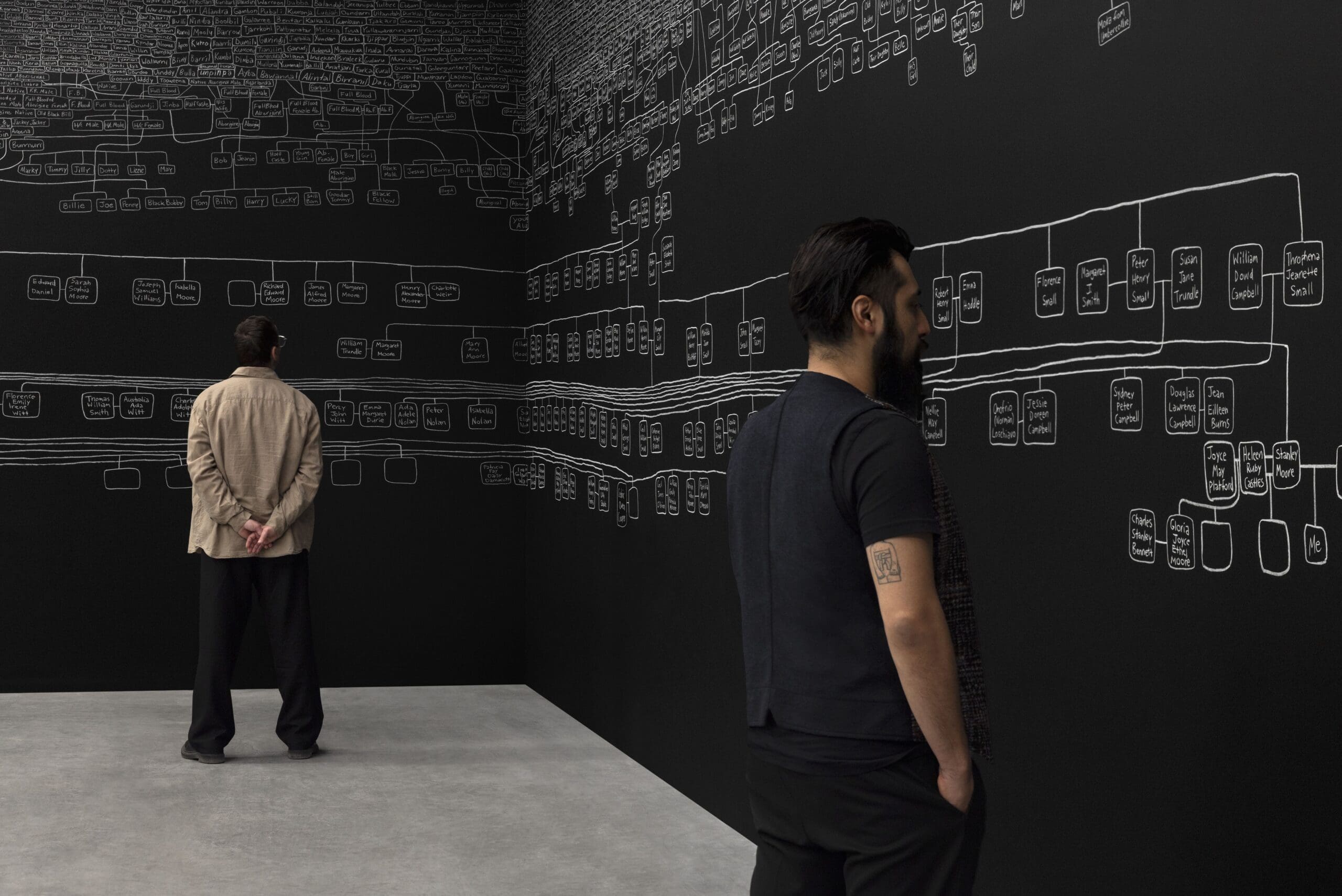

Instead, it announced a review into the process by which Sabsabi was selected. The same rigorous, independent process that chose Australia’s representative for the 2024 Venice Biennale, Archie Moore—who went on to win the event’s highest accolade, the Golden Lion.

The arts sector’s loss of trust in Creative Australia’s integrity, commitment to art and artists, and independence from government influence, has been well documented in the media. Australia’s peak arts organisation has been broadly condemned by its core constituency, with artists and art workers united in calling for it to reverse its decision and reinstate Sabsabi and Dagostino.

The widespread discontent has been compounded by Monash University’s decision in late March to indefinitely postpone another of Sabsabi’s projects: a group exhibition scheduled to open at Monash University Museum of Art in May, that was to have included “coffee-infused calligraphic paintings” and “abstracted silhouette works” drawing on Sufism, the mystical strain of Islamic spirituality that he adheres to. On May 22, the university reversed the decision, following a period of community consultation.

Sabsabi has described the knock-on effect of Creative Australia’s decision to drop him as the effective “dismantling” of his career and reputation, telling The Guardian it “essentially gave the go-ahead to define me as somebody who I am not.”

Every part of this story is shocking, but we should not be surprised because it’s just an extreme iteration of a scenario that has been playing out across the arts for years. Intensified in the wake of the 7 October 2023 attacks on Israel by Hamas, this activity is having a chilling effect on freedom of expression in the arts, previously considered a key arena for difficult conversations.

NAVA, the peak body for visual arts, is seeing a “growing number of instances where artists are being silenced, either explicitly through institutional decisions or more insidiously through self-censorship driven by fear,” says executive director Penelope Benton.

“The implications are not short-term. They’re profound and structural.”

Don’t talk about the war

Art Guide Australia spoke to artists, art-workers and curators to get a sense of the larger fallout of Creative Australia’s decision to dump Sabsabi and its longer-term implications.

We were told that the climate of silencing and censorship is disproportionately affecting a particular group of artists. As Cherine Fahd, a Lebanese Australian artist and academic, said: “This is not censorship of art; this is censorship of specific forms of art made by people of particular backgrounds and political persuasion.”

We also heard that it was not new. While everyone expressed shock and dismay at the dumping of Sabsabi, very few were surprised. “We know deeply, at the end of the day, that politics permeates every part of our lives,” said Lebanese Australian artist and arts worker Eddie Abd. “Especially in the arts, where there’s supposedly freedom of expression.”

Muslim, Lebanese, Palestinian and Iranian diaspora artists we spoke to said they’d experienced racism, silencing, de-platforming and censorship within the arts sector throughout their careers, and linked the campaign against Sabsabi to his identity as a Muslim and Lebanese artist—and above all, his stance on Palestine.

As the article in The Australian that spurred senator Chandler’s comments pointed out, Sabsabi was part of a boycott of the 2022 Sydney Festival over its sponsorship arrangement with the Israeli embassy, a decision he said he made “out of solidarity with the Palestinian people and the Palestinian cause”.

Hazem Shammas, a Palestinian diaspora actor who is on the management committee for Arab Theatre Studio in Western Sydney, says he’s experienced silencing and censorship throughout his 20-year career on stage and screen. “That censorship has always been applied because of Palestine.” In the wake of 7 October 2023, the censorship of artists over Palestine has intensified, he says.

Some of this activity has been highly publicised, including the National Gallery of Australia’s decision to cover up two Palestinian flags in a textile work by Aotearoa New Zealand collective SaVĀge K’lub. Pianist Jayson Gillham is suing the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra over a cancelled concert which he claims was linked to an effort to silence him over his position on Gaza.

There have also been highly publicised instances of arts organisations resiling from programming involving Palestinian and pro-Palestine artists, disinviting artists or indefinitely postponing programs. Those who have stuck to their guns have faced backlash, including Melbourne and Sydney Writers Festivals, where board members resigned over the programming of pro-Palestine artists and events. Sydney Theatre Company copped backlash both ways: its response to complaints about three actors who wore keffiyehs during a curtain call was criticised by artists for not taking a stronger stance on freedom of expression, and by Jewish patrons, donors and board members for not taking a stronger stance against anti-Semitism.

For the first time, the broader arts sector is seeing what those from the Middle East diaspora have always known: that Palestine is the third rail.

A media pile-on

There’s another part of the Khaled Sabsabi story that feels familiar to many of the artists we spoke to: the role of the conservative press.

Over the last two years, numerous artists, authors and musicians who have made public statements or social media posts relating to Palestine and the war in Gaza have been targeted by News Corp outlets, including Archie Moore and several high profile members of Eleven Collective, a group of Muslim Australian artists that includes Khaled Sabsabi.

Moore, an artist of Bigambul, Kamilaroi, British and Scottish lineage, was targeted as he was in the final stages of preparing his Venice Biennale project kith and kin. A Sky News report in December 2023, just months before the exhibition was due to open, called for him to be sacked as Australia’s representative, focusing on Instagram posts he had shared about the war in Gaza and accusing him of “appalling anti-Semitism” and “celebrating the terrorists that had slaughtered Israeli citizens” (claims that Moore unequivocally denied as part of a statement in response to Sky News’s coverage).

Eleven member Abdul-Rahman Abdullah says he has been targeted by News Corp repeatedly. In October 2024, The Australian published an article focusing on pro-Palestine social media posts by Abdullah, framing him as “a Labor-appointed member” of the National Gallery of Australia Council.

“I chose to resign from the Council to protect myself and the gallery from further attacks,” Abdullah told Art Guide. “I was the first Muslim council member and held the shortest tenure, as a result I doubt that another Muslim person will ever be appointed to the council.”

In the wake of the Sabsabi decision, Abdullah was namechecked in an article in The Australian questioning Creative Australia’s peer-assessed funding process—specifically, the “level of affiliation between the people on the assessment panels and the recipients making their case for funding”—focusing on grants received by members of the Eleven collective and the participation of members in the assessment process, and highlighting their social media posts and public statements.

Artist Hoda Afshar, another member of Eleven named in the article, was accused of making anti-Semitic remarks. Afshar says it wasn’t the first time she had been criticised in The Australian: “If I made a social media post about what’s happening in Gaza, or how it’s affecting us here, I would wake up to a Google alert, I’m in The Australian again.”

“There should be ways for me to challenge it [legally],” Afshar says. “But because they [The Australian] have lawyers to help them to frame these things with ambiguous wording, it makes it very challenging to fight a legal battle with them. And they also know that no artist can afford the legal fees.”

“Institutions love artists when it’s going well and when an artist is marketable, but as soon as things get challenging, we’ve seen artists get silenced, or seen parts of works get covered or exhibitions dropped.”

—Bruce Johnson McLean

Bruce Johnson McLean, a Wierdi man and curator who worked at Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) and the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) over two decades, says: “There’s a very well-established tactic now where any voices that are different, any ideas that are different, can quite easily be cancelled by conservative media.”

Johnson McLean says he experienced this firsthand while working as head of First Nations art at NGA. He and colleagues were preparing an exhibition of APY Lands art when The Australian aired allegations in April 2023 that works attributed to Indigenous artists from the APY Arts Centre Collective (APYACC) were substantially made by white assistants. Days later the NGA announced an investigation into the provenance of paintings from APYACC that were due to appear in their show, titled Ngura Pulka. The following month, the South Australian and federal governments announced a joint investigation into the APYACC. Neither found evidence to substantiate the allegations, but the Ngura Pulka exhibition was postponed while the reviews were underway.

“The National Gallery, as a government institution, felt that it had to indefinitely postpone the exhibition,” says Johnson McLean. The NGA has yet to reschedule Ngura Pulka and did not respond to requests for comment.

Johnson McLean says he believes in cases such as Khaled Sabsabi and the Ngura Pulka exhibition, the media is “weaponising the public” to get certain outcomes. “The exhibition came up in the newspapers, and that story was run every few days, to make sure that there was a public backlash,” he says.

Johnson McLean said he was “shocked but not surprised” by Creative Australia’s decision to cancel Sasabi’s Venice Biennale commission.

“A lot of arts organisations are pretty soft targets; they are often left fairly voiceless or powerless in the face of the media—particularly the Murdoch media—or conservatism more broadly,” he said. “They seem to very quickly get on the back foot and retreat behind institutional governance to essentially make the problem go away.”

Johnson McLean links this to the rise in “risk management” practices in the sector across the last decade. “With an increase in risk management has come the increase of risk aversion, and a move away from challenging art.”

He says the Khaled Sabsabi sacking marks a “critical point” in a “trajectory of institutions and artists diverging”.

“Institutions love artists when it’s going well and when an artist is marketable, but as soon as things get challenging, we’ve seen artists get silenced, or seen parts of works get covered or exhibitions dropped.”

Behind-the-scenes harassment

Even before Afshar was targeted by The Australian, she was experiencing wide-ranging harassment and intimidation online, including hostile comments on her social media posts and intimidating direct messages, which were also sent to friends and followers who responded to her posts.

In one particularly nasty case, she was told that someone had bought a tree in her name, to plant in the home of a Palestinian family that had been occupied by Israeli settlers.

She says donors have pressured institutions to cancel exhibitions featuring her work and threatened to withdraw funding.

Other artists described similar experiences but would only speak to Art Guide on condition of anonymity, concerned about further attacks. One said: “lobbyists have repeatedly contacted the commercial galleries that I work with saying that they will boycott the entire gallery roster and encourage others to boycott the gallery as well unless they drop or silence me.” Another said: “It feels like a coordinated campaign … anyone working with me, or associated with me gets pulled into the vortex with accusations of racism and even the suggestion of legal action.” Another artist reported that a collector pressured their gallerist to drop them. “They were threatening that if not, they would stop buying art from him,” the artist said.

“I am concerned that a generation of artists—artists who are making important, rigorous work, who are self-reflective and creating nuanced discussion—will not come forward for opportunities that open their practice to a platform outside of the spaces they are already working within.”

—Joanna Kitto

Joanna Kitto, director of Melbourne arts space West Space, says she’s hearing from artists who are concerned about “their safety in online spaces, being bullied, or their name appearing in a newspaper in a negative context”.

“I’ve been working a lot with Palestinian artists, and they are definitely feeling the pressure,” says Abd. “They are trying to figure out ways of being true to themselves and speaking out, but also feeling the weight of censorship.”

To artist Cherine Fahd, the fact that people won’t speak on the record is chilling in itself: “It’s like living in a surveillance state … People are rightly suspicious, untrusting, and very guarded about what they say on the public record.”

The bigger picture

In this climate of silencing, censorship and suspicion, artists and arts workers with certain values, political views and backgrounds are not only retreating from social media and mainstream media, but they are also retreating from major institutions and opportunities.

“We’ve seen huge impacts on artists, on arts workers, and particularly on the sorts of people that we want in the industry, who are dedicated to supporting artists,” says Johnson McLean. “People [are] walking away because they don’t agree with the direction that things are heading.”

Johnson McLean says staff left the NGA in the wake of Ngura Pulka’s postponement. He was one of them, resigning from the NGA in May 2024 after almost five years. “I truly believed that I could support artists better elsewhere,” says Johnson McLean, who has since been appointed Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain First Nations curatorial fellow for the 25th Biennale of Sydney.

Cara Kirkwood also left her role at NGA, in mid-2024, after three years as head of First Nations engagement and strategy, including serving as creative producer and cultural strategist for the SaVĀge K’lub exhibition.

Kirkwood, a Mandandanji and Mithaka woman, told Art Guide: “Me and many of my friends have been heartbroken by the scarcity of leadership across the nation. Where are the highest paid salaried workers’ and their advocacy on the true impacts of art and creativity at a time when we need it most? … The incongruence of public services’ declarations of ‘neutrality’ at the cost of human and cultural erasure is heartbreaking.”

Other high-profile departures from the top end of the sector include Creative Australia’s Head of Visual Arts, Mikala Tai, and Venice Biennale project manager, Tahmina Maskinyar, who both resigned in support of Sabsabi and Dagostino. Maskinyar has since been appointed curator at West Space.

At the emerging end of the sector, West Space director Joanna Kitto says she is having conversations with artists who are “genuinely wondering if the arts is for them”.

All the curators and arts workers Art Guide spoke to noted the scarcity of leadership from the top end of the sector during the Khaled Sabsabi saga, and the disproportionate weight borne by artists. Kirkwood put it best: “Time and time again, shockingly, poorly paid artists are left to do the heavy lifting without the bureaucratic infrastructure to help navigate or influence media, public or political aggression.”

The artists Art Guide spoke to said that they would not change the kind of work they made, but many said they were more careful about where they took up opportunities, screening organisations for funding sources and the membership of their boards. They were more likely to work with grassroots, community-focused and independent organisations who they could confidently expect to protect their freedom of expression.

“I am concerned that a generation of artists—artists who are making important, rigorous work, who are self-reflective and creating nuanced discussion—will not come forward for opportunities that open their practice to a platform outside of the spaces they are already working within,” says Kitto.

“Artists’ voices will be heard by those who are listening, but we run the risk of losing their input on the broader stage—reaching those outside of Australia, and outside of the art sector bubble—where we need them the most.”

The other curators we talked to agreed, with Johnson McLean predicting that “as institutions become more risk averse, what we will see in those spaces is a flattening of art” and a shift towards “Instagrammable fun stuff”.

“We need to ask ourselves: how did we get here? How did we fail to protect the values—freedom of speech, democracy—that we worked really hard towards?”

—Hoda Afshar

Ultimately, this shortchanges the vast majority of audiences who experience art through major institutions. If artists whose art or beliefs disrupt the status quo are excluded or exclude themselves, we risk turning galleries into feedback loops or mere pleasure palaces; we risk short-circuiting art’s function as a connective tissue between different perspectives, communities and experiences, and as a testing ground for new ideas. And all this because of decisions and conversations happening in boardrooms and behind the scenes—without the input of the public.

Meanwhile, this leaves the small to medium sector—organisations such as West Space, which has made its position on Palestine (an issue of conscience for many artists) clear, and Arab Theatre Studio, which is committed to its artists’ self-determination—carrying a larger load of producing the nuanced, complex art that speaks to our society right now.

Much of this sector is heavily reliant on government funding, and the curators and arts workers we spoke to were all concerned about the potential dismantling of Creative Australia in the wake of the Sabsabi backflip.

Anne Loxley, executive director of Arts and Cultural Exchange (ACE) in Western Sydney, which receives roughly 80% of its funding from government sources, said: “If this gives conservative thinkers more reasons to dismantle arts funding, then things are really desperate.”

Even a change to the current peer-review model for assessing funding, could be disastrous for artists, and the artists and arts workers we talked to said this was a key concern for them. Abd told Art Guide: “[The current funding model] is at arm’s length from politicians, from government, and personally, for my own development as an artist, I’ve been a part of a couple of programs supported by Creative Australia that benefitted me so much. And in terms of funding for projects that I do as an arts worker, it has been fantastic.”

And yet: for all their concerns about their own practice and livelihoods and freedom of expression, the artists we talked to kept drawing the conversation away from the arts and towards the bigger picture.

Fahd expressed a shared sense of frustration when she said: “Suddenly everyone has something to say about the censorship of Khaled. [But] this is not happening in a cultural vacuum. This is happening during a genocide that our government has sat silent on, and that’s why Khaled has been cancelled.”

Hoda Afshar said what is happening in the arts is “clearly pointing to the rise of fascism”. “We need to ask ourselves: how did we get here? How did we fail to protect the values—freedom of speech, democracy—that we worked really hard towards?”

Afshar says this moment “has been in the making for a long time”, and calls to mind author and activist Behrouz Boochani’s letter from Manus Island in 2017, while he was imprisoned in refugee detention, which was addressed to the Australian people.

“He said that if you ignore what’s happening beyond these shores, to the people on Manus and Nauru, remember: this creature of fascism is growing its roots, and one day you will find it inside your own homes. And that’s where we’re at now, eight years later: it’s inside our homes, and it’s affecting every single one of us.”

Dee Jefferson is an editor, journalist and critic with two decades experience covering culture, previously as national arts editor for the ABC and Time Out, and currently as a culture reporter for Guardian Australia.

Editor’s note: Khaled Sabsabi was reinstated as Australia’s representative for the Venice Biennale on July 2