Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Outside the Frame is a sly title for a book about the moving image in art. “Despite its now regular presence in contemporary art galleries, there is no doubt that time-based art can be intimidating for some audiences,” writes art historian Kate Warren in the book’s opening essay. The pace of technological change can worry collectors but there are also the demands of the work itself, to which Warren admits, “It takes time to watch—sometimes a lot of time.”

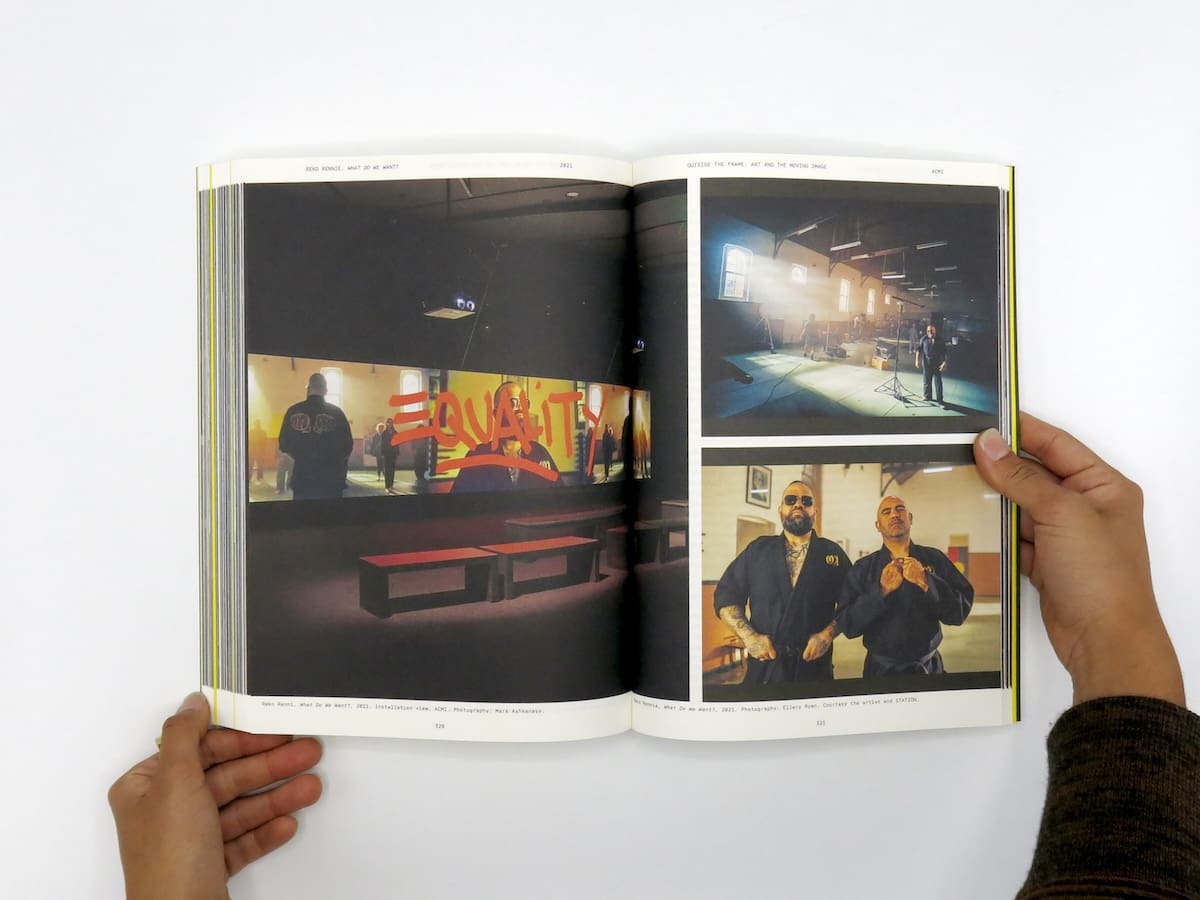

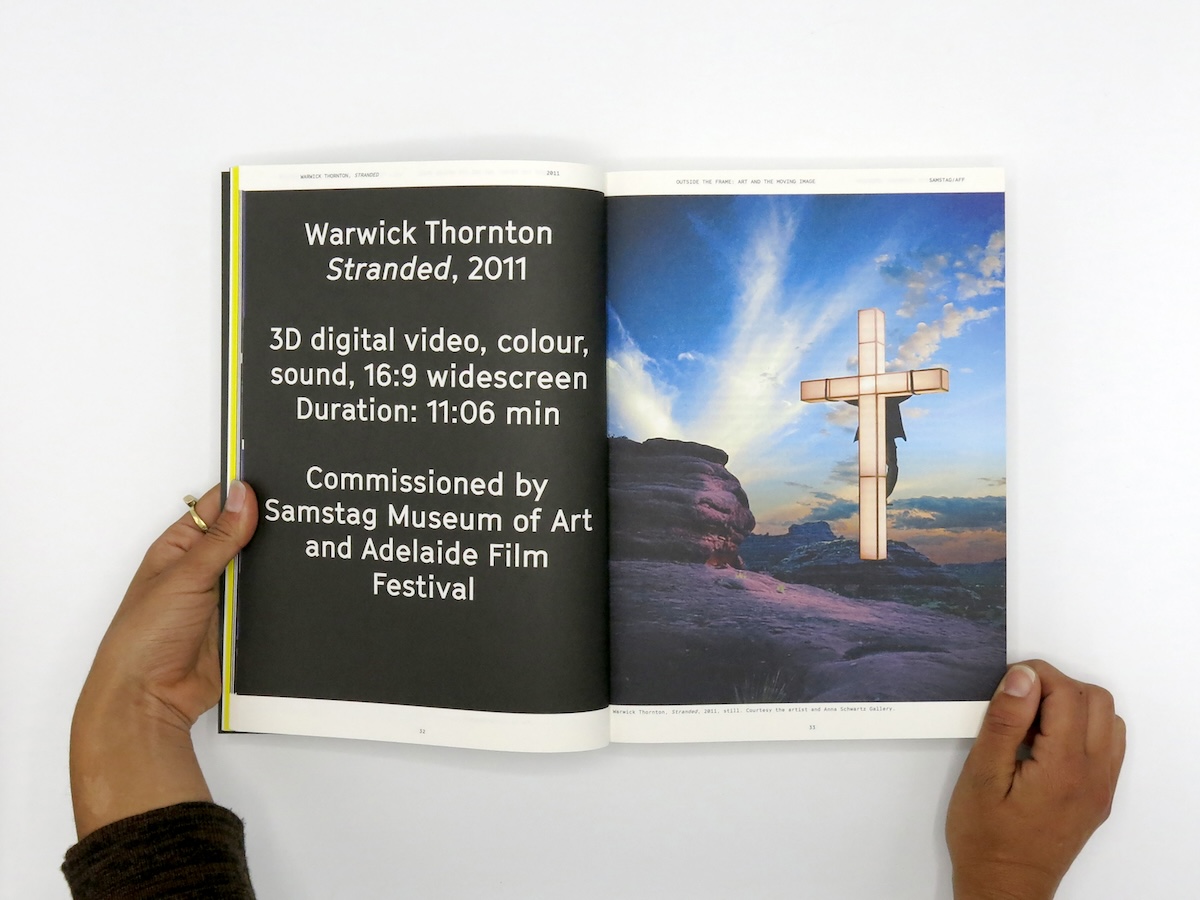

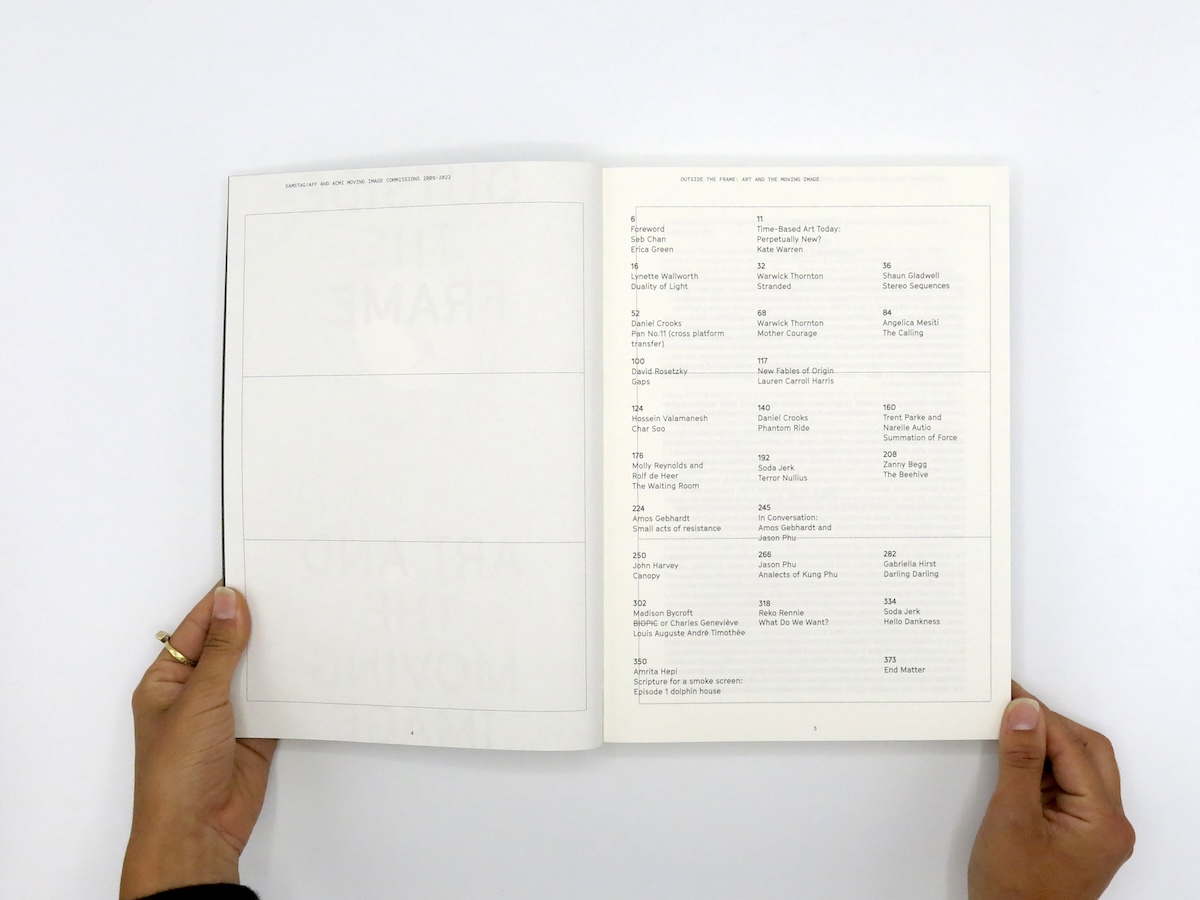

With so few collectors of the moving image, Warren argues that institutions play a critical role in supporting artists through the commissioning of new work—and that’s really what Outside the Frame is about. The weighty new book is a partnership between ACMI in Melbourne and the Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide, and presents 21 of their recent moving image commissions. It opens with Lynette Wallworth’s groundbreaking Duality of Light (2009), supported by Samstag and the Adelaide Film Festival, and includes many critically significant works, from Warwick Thornton’s Mother Courage (2013), to Zanny Begg’s experimental documentary The Beehive (2018) and Amos Gebhardt’s Small Acts of Resistance (2020).

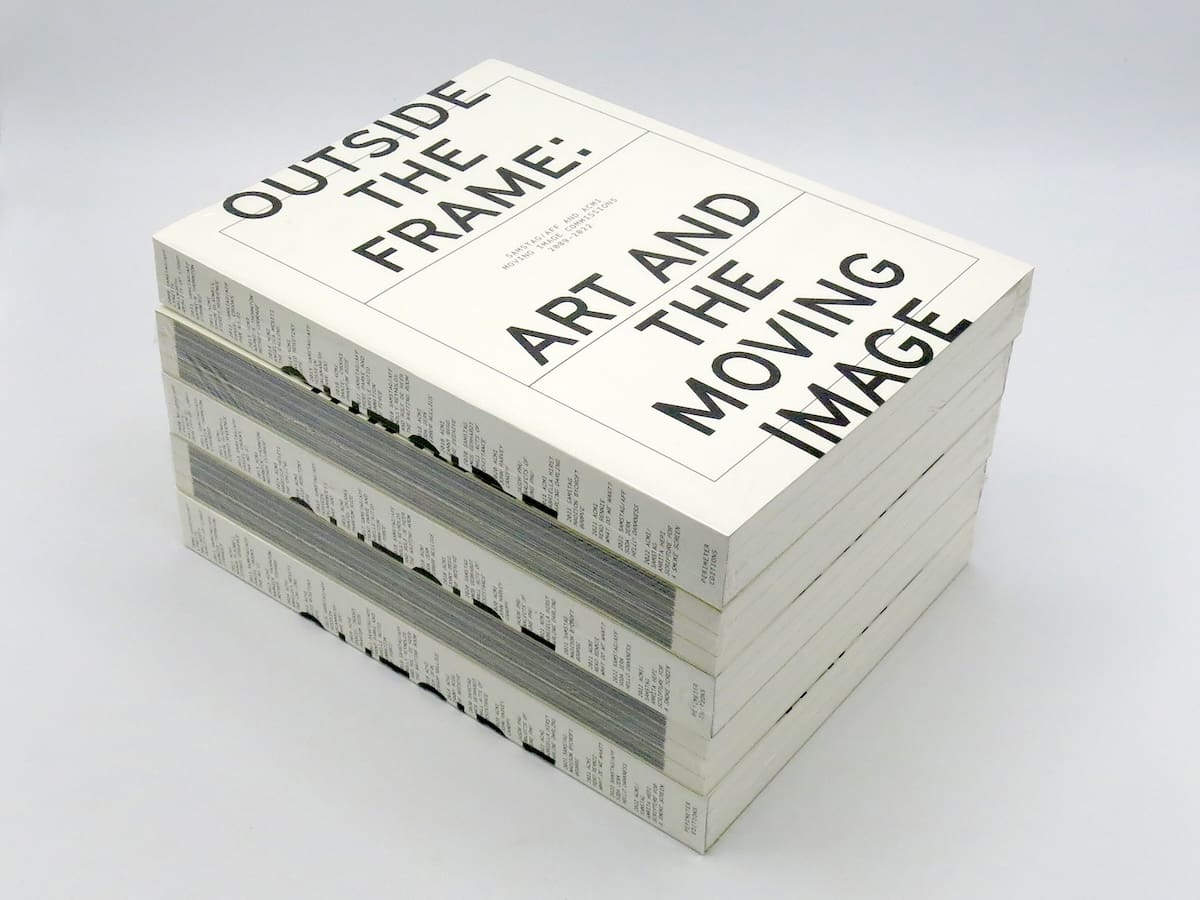

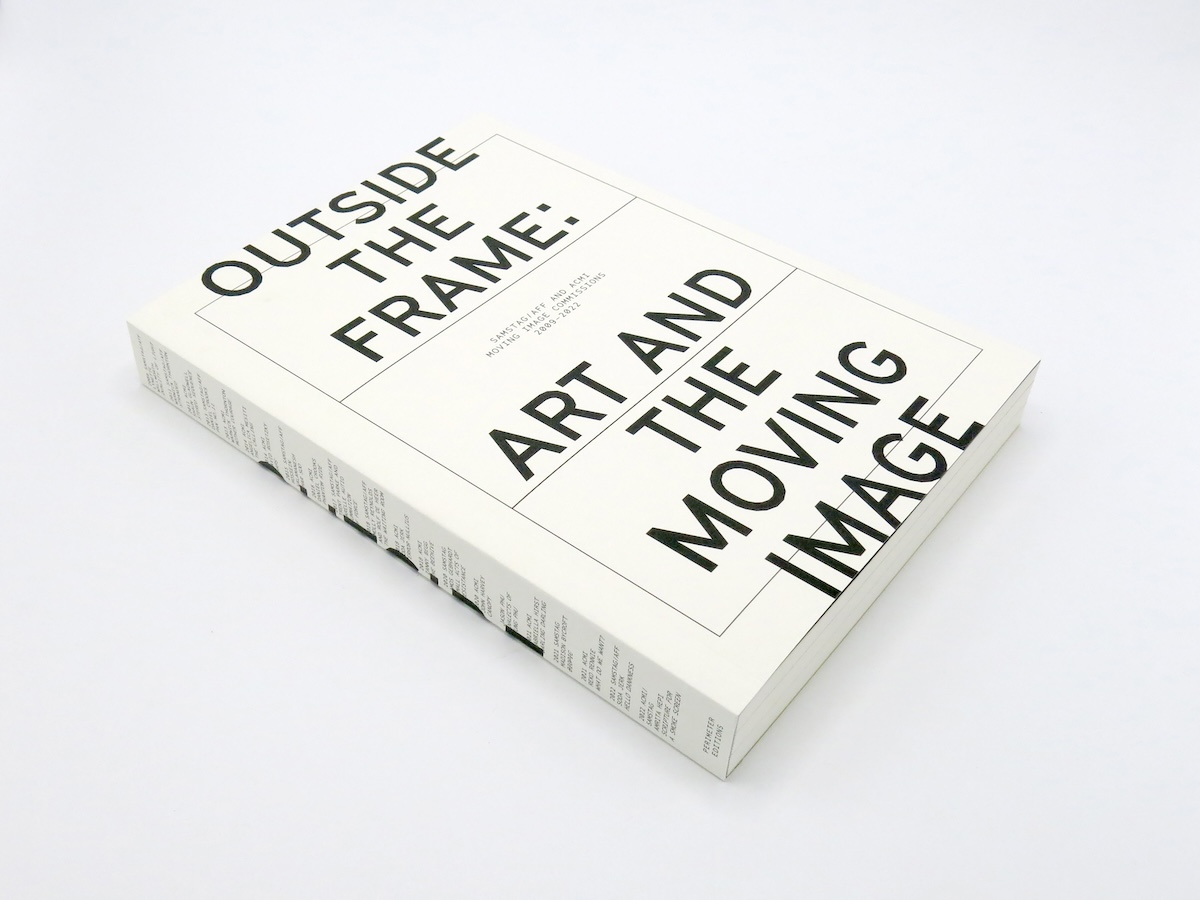

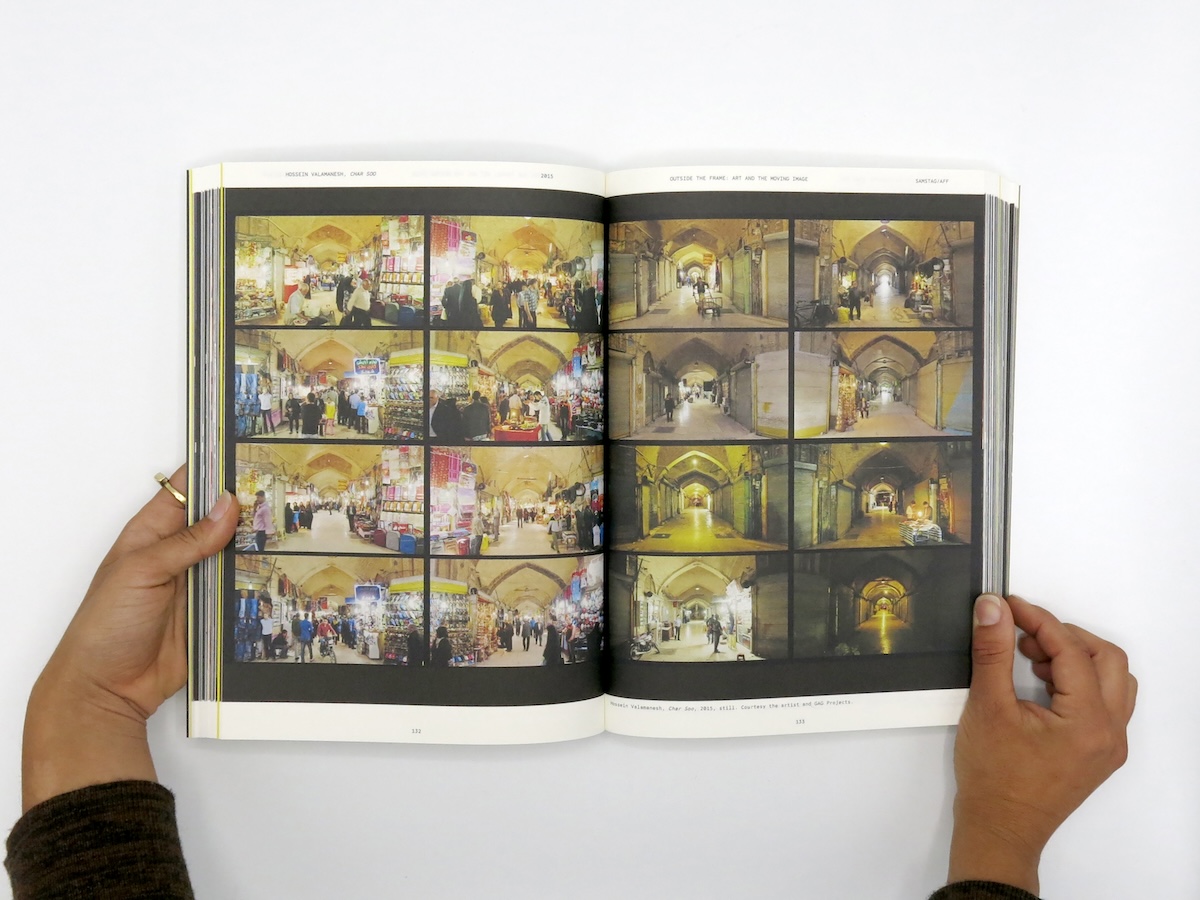

Outside the Frame has been beautifully produced by Perimeter Editions, a publisher known for its careful attention to small details. Each commission is given a generous run of images and is accompanied by its original catalogue essay. The entries stand alone, but shared interests quickly emerge. Several works explore language and its limits, like Angelica Mesiti’s The Calling (2013-14) and David Rosetzsky’s Gaps (2014). Others investigate the experience of time and movement, particularly Daniel Crooks’ Pan No.11, Cross Platform Transfer (2013) and Phantom Ride (2016). There are also brilliant examples of how multi-channel works can be installed to implicate the viewer in a work and draw out questions around perspective and choice, including Hossein Valamanesh’s Char Soo (2015) and Gabriella Hirst’s Darling (2021).

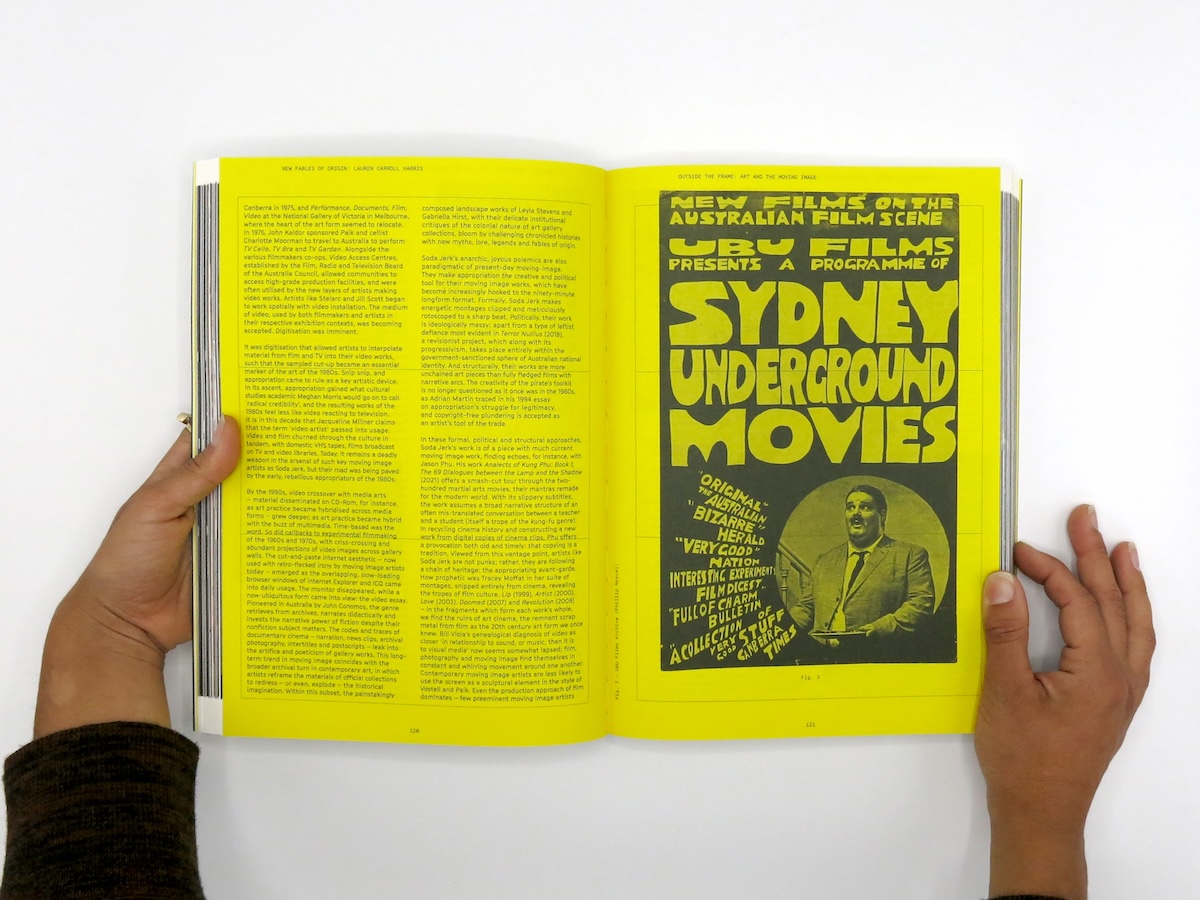

As a slice of contemporary practice, the 21 commissions in Outside the Frame have a lot to say but these threads are largely left for readers to discover. The reliance on historical catalogue texts sets the focus on the individual works, though three new texts provide some broader context. In her opening essay, Warren unpicks the medium’s conflicted identity as ‘perpetually new’. There is also an interview with artists Jason Phu and Amos Gebhardt that sheds light on the intricacies of working in this space, as well as a powerful historical essay by the writer and researcher Lauren Carroll Harris. Here, she explores the connections between experimental practice and filmmaking and the wider social changes that have influenced the medium’s path, but the wide references to other artists and filmmakers also bring home the difficulty of structuring a book around commissions.

No one wants to read about selection criteria of course, but if these 21 works are being presented as things ACMI and Samstag have decided to spend money on, then it would help to know more about what these institutions value. Why these artists? What do these choices represent? In her foreword, Samstag director Erica Green acknowledges the work in progress when she notes “Fortunately, there is still a deep well of projects, artists and filmmakers we have yet to tap.”

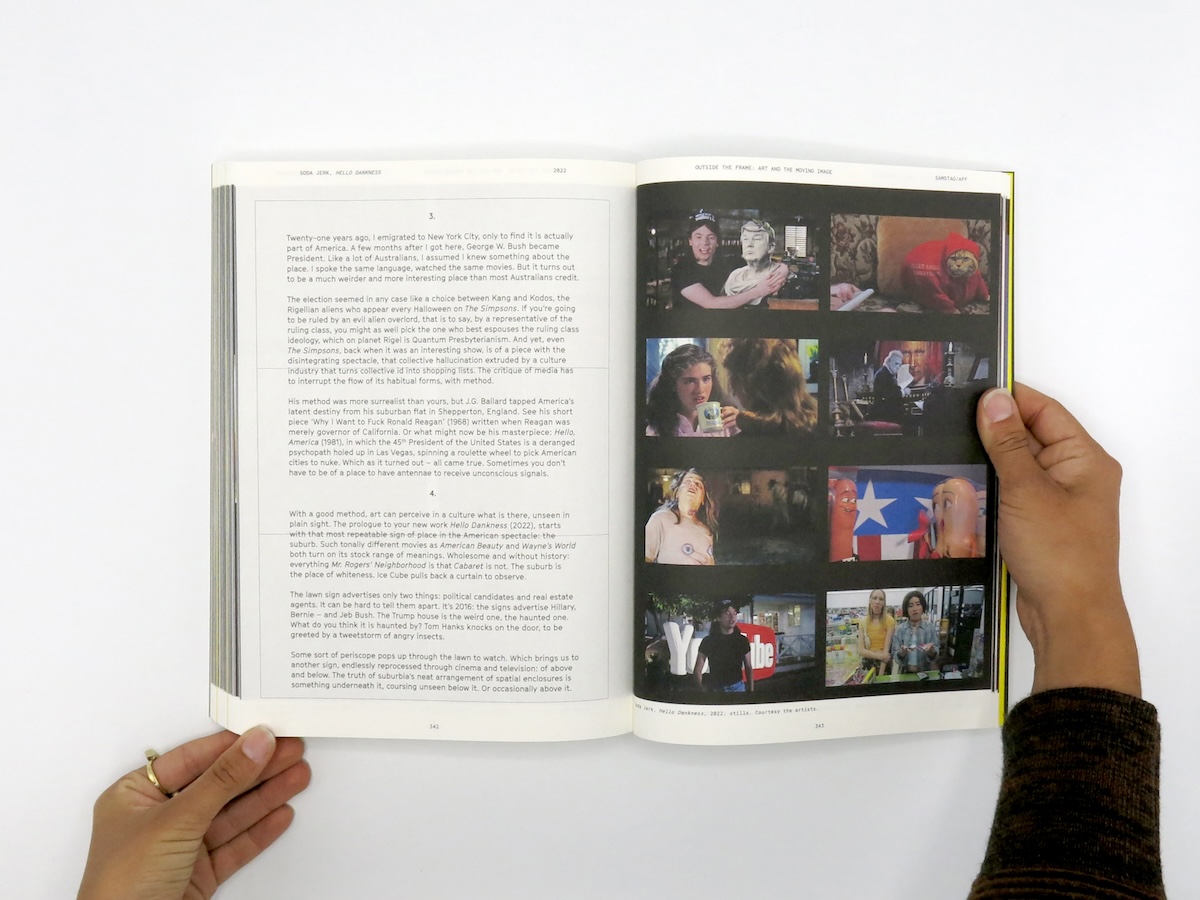

Joan Ross, Dr Christian Thompson and Tully Arnot, the three artists who received ACMI’s short-lived Mordant Family VR Commissions, are not included. The quiet background to Outside the Frame is that money is never permanent in the arts. The projects captured here have been supported by numerous funding initiatives, like the now expended ACMI $100,000 Ian Potter Moving Image Commission. There’s also the sensitive question of unspoken expectations. Soda Jerk’s Terror Nullius (2018) was created with an Ian Potter Moving Image Commission only for the Ian Potter Cultural Trust to later remove its name from the work’s publicity and marketing. The artists went on to make the epic politico-disaster film Hello Dankness (2022) with a Samstag/Adelaide Film Festival commission, also featured in Outside the Frame, yet Terror Nullius remains a moment in Australian culture for mixed reasons.

In the essay that accompanies Terror Nullius in Outside the Frame, the artist and writer Jessie Scott describes the history of video art as a choose-your-own-adventure story. It’s a mongrel medium, she says, built by practitioners in multiple modes using divergent tactics and methods. That persists in how we talk about it too. “As a national arts culture, we seem incapable of retaining our historical knowledge of, and connections to, the video practice(s) of the recent past, let alone its increasingly distant origins,” she writes. Outside the Frame is a substantial addition to this imperfect record, and one that brings many critically significant works back into view.

Outside the Frame: Art and the Moving Image, published by Perimeter Editions x Samstag Museum of Art, University of South Australia x Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI).

You can purchase Outside the Frame from the Art Guide Bookstore.

Subscribe to the Art Guide Bookstore to stay up-to-date with our curated guide to Australian art publications.