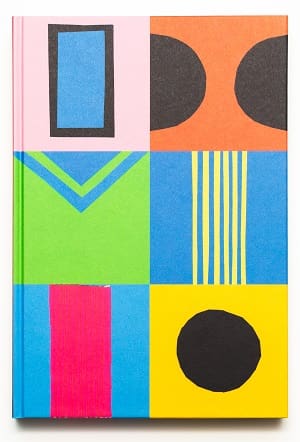

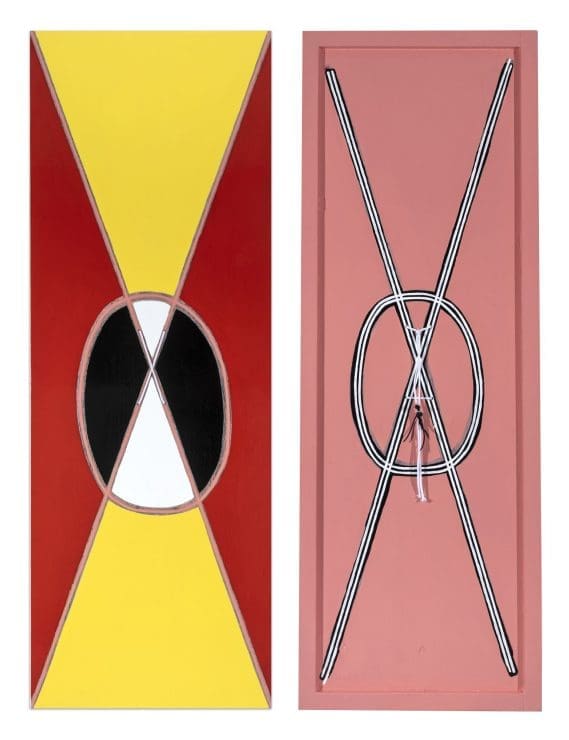

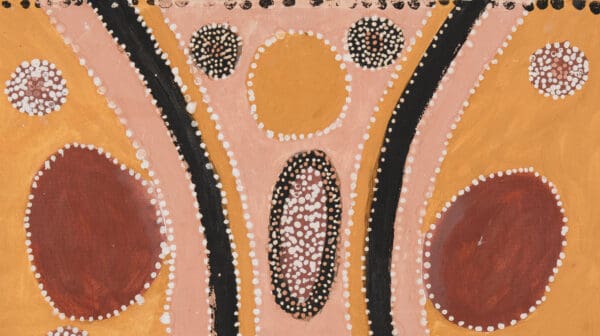

There’s a graphic punch to the Yuriyal Bridgeman’s Yubilong(mi)bilongyu. The monograph, also titled You Belong to Me and I Belong to You, follows Bridgeman’s major solo exhibition at the Griffith University Art Museum, bringing together almost two decades of his painting, photography, video, installation and sculpture. The cumulative effect is mesmerising. The painted shields in particular, with their deep ties to Papua New Guinea and bold geometric designs, give the book a pulsing, rhythmic energy. Bridgeman often chooses to exhibit these shields in groups, echoing their cultural use in war, but they gain new power gathered together within 150 pages of a book.

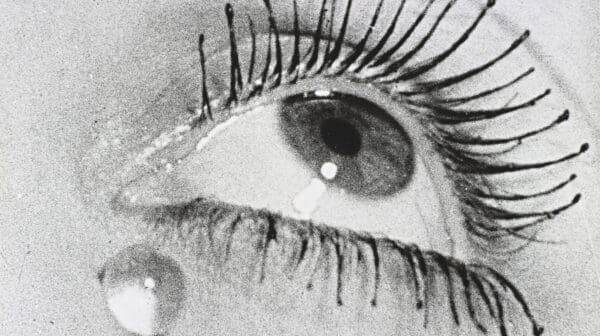

Visually, the monograph is a thrill. The photographic work, especially the self-portraiture, is the connecting glue between the different fields of his practice. Some works, like Boi Boi the Labourer (2008) and Willy with Bilum (2013), offer the same bold, graphic hit as the painted shields. Others are more tender, even unsettling. Godmother’s Fish (2024) shows the artist sitting by a neglected suburban swimming pool, a Narcissus figure strumming a dead fish. Portrait of Man in Boarding House (2007) captures a young tradie in a hard hat—a frequent motif in Bridgeman’s work—in a destroyed, uninhabitable house. Identities are slippery things in these works. And that’s where the monograph also comes unstuck.

As an artist, Bridgeman is driven by his need to explore his own cultural identities. He grew up in Australia, and it was only after graduating from art school in 2008 that he began seriously exploring his family ties to Papua New Guinea. Eventually, he was spending so much time there that he built his own roundhouse, though it’s much more than a home. It’s also the centre of the artistic community group he co-founded, Haus Yuriyal. He now lives between Meanjin and Papua New Guinea and his work is frequently collaborative, such as in SUNA (Middle Ground) (2020), a roundhouse built with Haus Yuriyal for the Biennale of Sydney. He has also taken on the first name Yuriyal, given to him by his late cousin, in a further sign of his ties to his heritage.

Bridgeman’s works often resist easy categorisation. It makes sense then that the monograph avoids setting down a single authoritative account. Instead, it tries to capture the complexity of his approach to his cultural roots and the community side of his practice by offering a variety of perspectives. Yubilong(mi)bilongyu brings together essays and interviews from 12 contributors, including editors and exhibition co-curators Sana Balai and Angela Goddard, artists Khaled Sabsabi, Pat Hoffie and Archie Moore, and Yuri elder and community activist Joe Kuman. Some of these contributions are powerful—Kuman’s cultural history included—but it’s an uneven and often chaotic collection.

The starting point is an interview between the artist and Veronica Gikope, though it’s not immediately stated that Gikope is his mother. Leading with family is a smart choice when it comes to an artist like Bridgeman, but in this case, the easy familiarity makes for a confusing entry for readers. The chronological details are piecemeal. A lot is assumed. The next essay, by curators Sana Balai and Angela Goddard, sets down a more traditional account of Bridgeman’s career, but it has similar problems, with the acquisition of land for Haus Yuriyal mentioned before the group or its importance are fully introduced. These small inconsistencies make for a frustrating start. The editing feels rushed. The placement of artwork images and captions also means a lot of flipping back and forth.

There’s still a lot to appreciate about this polyvocal take on Bridgeman’s practice. Pat Hoffie’s essay on his photography and self-portraiture is key. Archie Moore also introduces the vital concept of double consciousness, or the viewing of the self through both one’s own eyes and the prejudices of the dominant white world, though arguably this shouldn’t have come in the last essay of the book. There is also an engaging cultural history of shields by curator and academic Michael Mel, and an essay on Bridgeman’s use of wheelbarrows in his sculptural works by curator Ruth McDougall, though there’s probably a lot more that could be said about Bridgeman’s interest in the language of tradies and sport in the context of the Australian art world’s deep class problems.

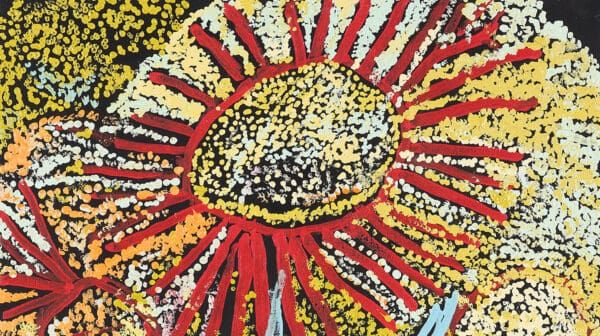

The monograph is also missing a solid discussion of Bridgeman’s most recent paintings. These include restrained geometric abstractions, created with light sprays of colour over masked lines, as well as collaborations with Haus Yuriyal, painted in alternating colours on the horizontal lines of garage doors. They are presented with passages from Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Colour, which Bridgeman had friends translate from the original German to Tok Pisin and from English to Yuri. It’s another strong statement that this is an artist concerned with acts of perception and translation. As Balai and Goddard remind us in their essay, “Bridgeman speaks many languages, artistic and otherwise.”

If you’re interested in reading further, Yuriyal Bridgeman’s ‘Yubilong(mi)bilongyu’ can be purchased from the Art Guide Bookstore. Visit us in store (43–47 Simpson Street, Northcote 3070, open Wednesday – Saturday 9am – 5pm) or online.