Two recent publications on the work and research of artist Yhonnie Scarce find very different ways to challenge the status quo of arts publishing. One strives to give the groundbreaking artist her full dues. The other, coming out of the artist’s collaborative research project with Lisa Radford, shifts the focus to the others working with similar questions. As Jane O’Sullivan writes, both publications have a lot to say about how the artist thinks, but also how we talk about the contemporary relevance of their work.

Jon Campbell’s portrait of artists Yhonnie Scarce and Lisa Radford, Pain Hope Work Sing (2025), is currently hanging in the Salon des Refuses in Sydney and shows the two collaborators standing like boxers, the words of the title collaged across their knuckles like tattoos. Scarce has often been framed as a fighter. It’s par for the course for First Nations artists when arts criticism often glosses over artistic skill to focus solely on trauma or identity-based narratives. But Campbell’s portrait also taps into an important shift in the way Scarce’s work is being talked about, and that’s not by chance.

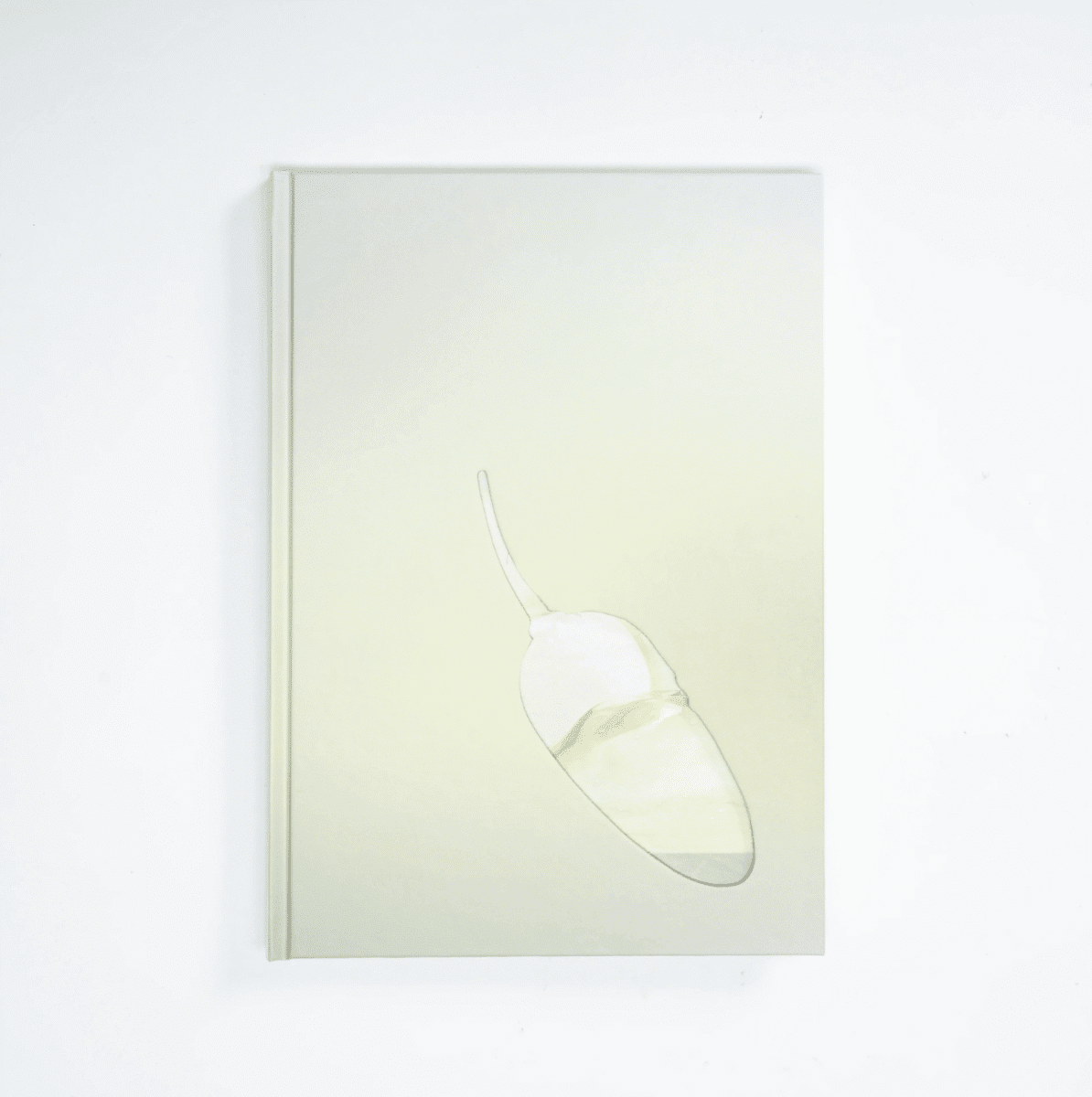

Yhonnie Scarce: The Light of Day was published to accompany Scarce’s major solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2024. In a positive step, the monograph on the Kokatha and Nukuna artist was shepherded into form by a team led by Indigenous women: senior curator Clothilde Bullen, a Wardandi, Kaniyang and Badimaya woman, and editor Timmah Ball, a writer, artist and curator of Ballardong Noongar heritage. Their guidance is most obvious in the effort to talk to the work, not around it, and to give the groundbreaking artist her full dues.

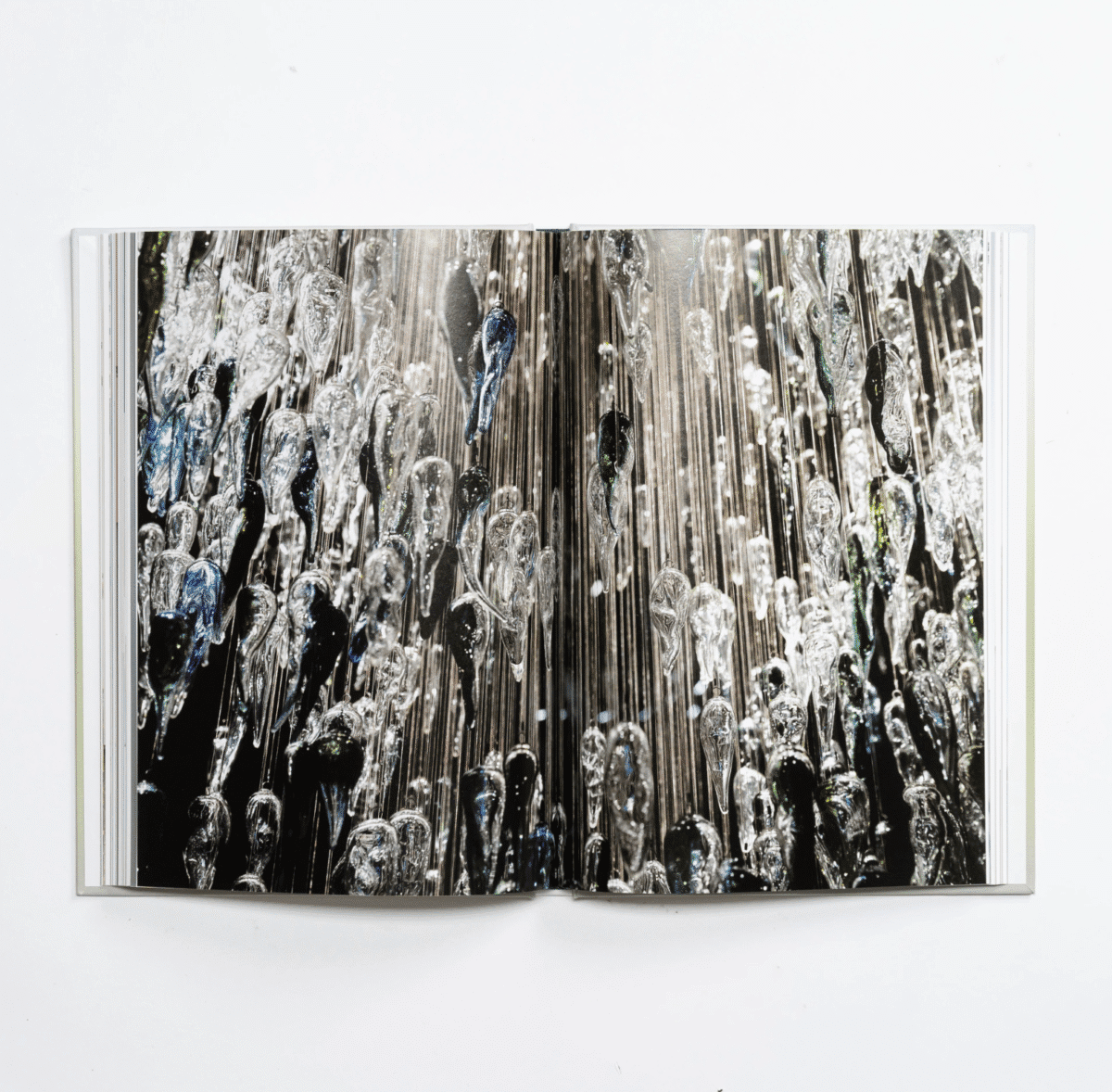

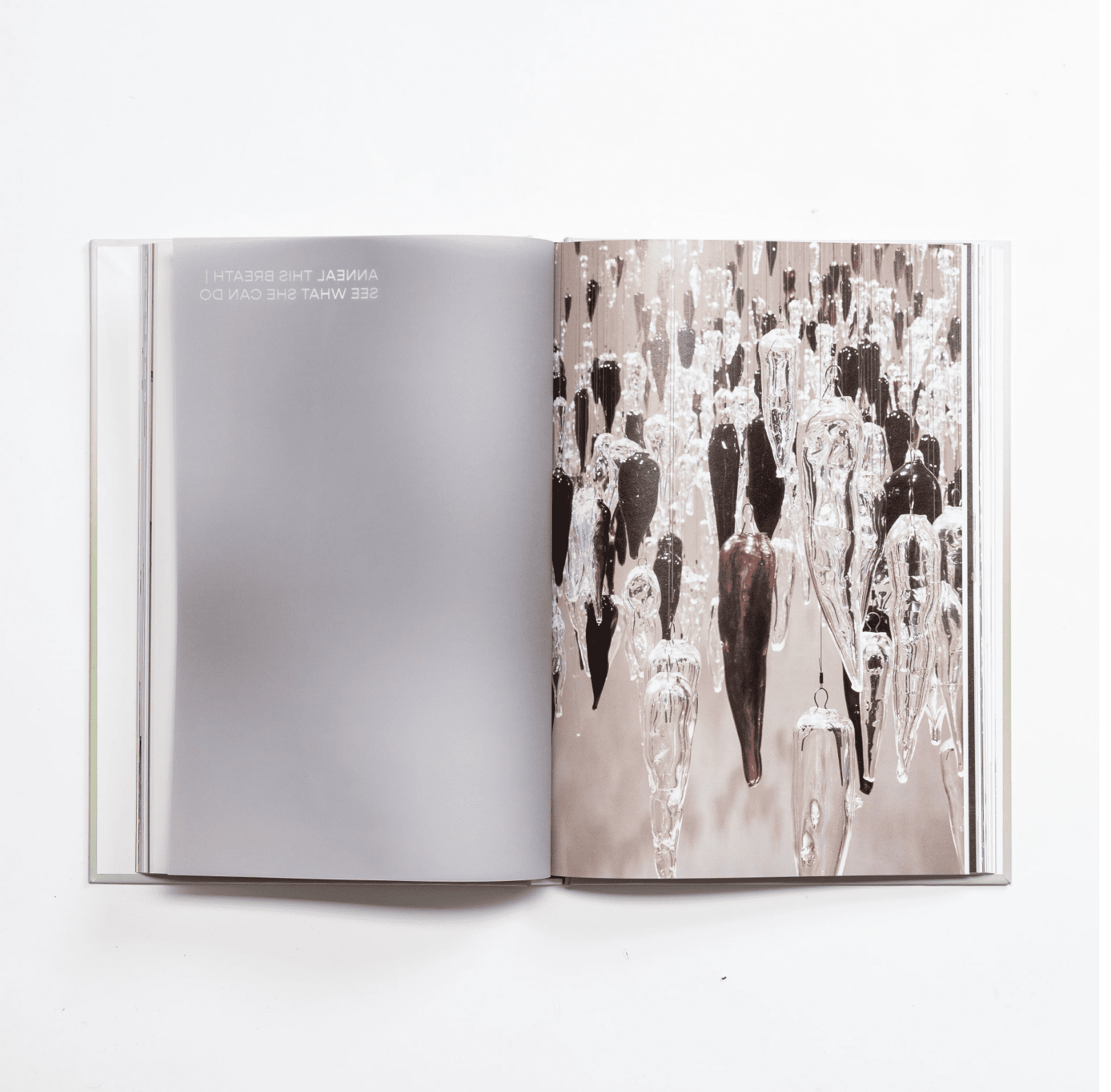

When The Light of Day was recognised in Art Association of Australia and New Zealand’s publishing awards last year, it was praised for its original contribution. Scarce’s connection to Country and family is front and centre, but the essays and interviews also pay careful attention to how she works with her materials, the techniques and metaphors she uses, and her strength as a glassblower. As Ball notes in her opening essay, glass is so ubiquitous we rarely pay attention, but that changes in Scarce’s hands. “We know glass breaks easily—it is inherently fragile—but Scarce also reveals the moments when it holds its form,” she writes.

There is historic context here too, of course. The essays document the devastating nuclear tests conducted at Maralinga in the 1950s and 1960s, exploring how they have shaped Scarce’s life and purpose as an artist, and informed critical works like Thunder Raining Poison (2015) and Death Zephyr (2017). But as Ball says, the writing here is about diffusing “the inclination to view her work as purely historical”. The five essays build a compelling account of contemporary relevance and artistic skill alongside a story of survivance, and that approach is reaffirmed in the wonderful final interview between Bullen and the artist.

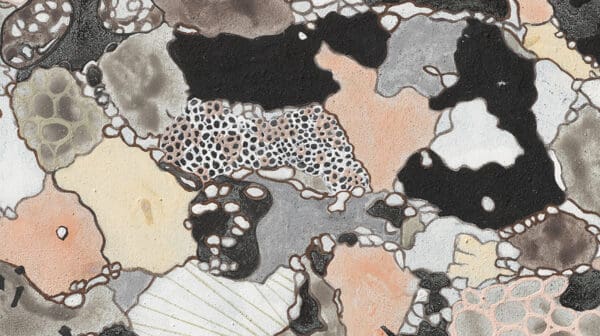

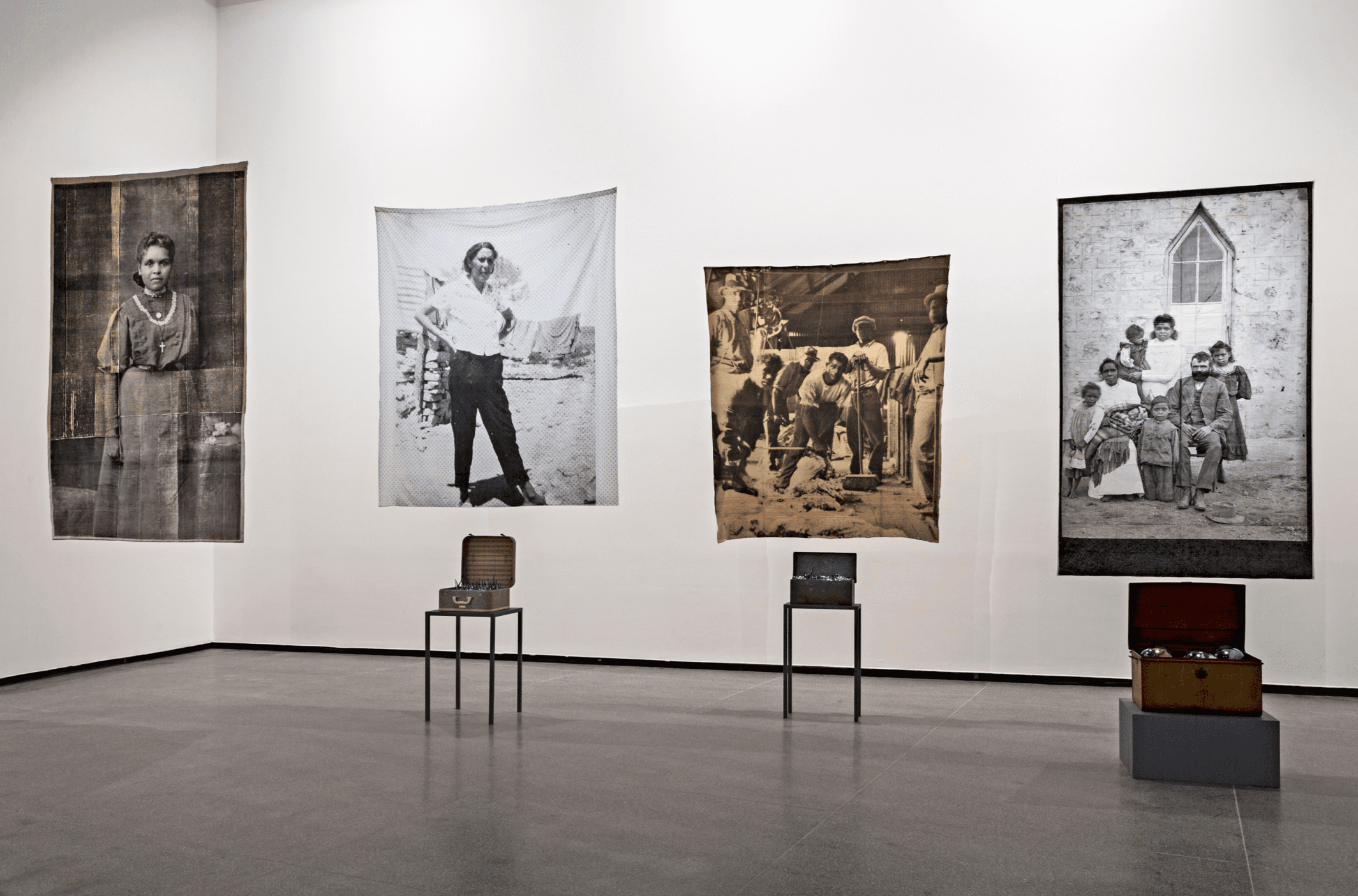

What The Light of Day does particularly well is show the breadth of Scarce’s practice. The essays and images show the different forms, colours and textures that Scarce coaxes from glass, with pieces cut or punctured, or banded in metal shackles. The monograph also explores her use of a wider set of materials, including the family photos, found objects and textiles in Remember Royalty (2018), the major work jointly acquired by the Tate and Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

Intriguingly, this also extends to her interest in architecture and built memorials. Scarce travels frequently, and has been researching genocide internationally since 2008. In The Light of Day, that comes out in brief discussions of her public commission In Absence (2019) with Edition Office at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, and her collaboration with the artist, writer and academic Lisa Radford.

Over several years, the two visited local and international sites of nuclear colonisation, genocide and memorialisation. They documented sites included Maralinga, Wounded Knee and Chernobyl, largely as a way of thinking through the kinds of events are deemed worthy of marking and those that are not. The collaboration, The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives) (2018-2021), ultimately produced a group exhibition at ACE in Adelaide and Margaret Lawrence Gallery in Melbourne, a durational archival project with Art+Australia and a substantial print publication.

If The Light of Day is a formal account of the artist’s methodologies and skill, then this publication is much looser, more like a hybrid biography of ideas and shared reference points. Presented in a sturdy cardboard box, the series of softcover, zine-like publications includes editorials written over 2020, field photographs, an exhibition catalogue, and an eclectic mix of invited essays, artworks, poems, research and historical documents. It’s a lot like a box from the archives, in fact, or at least something that has to be sifted through with care. There’s an art essay by contemporary critic Tristen Harwood, academic research tallying queer memorial sites, and a 1976 interview on white culture’s flawed representations of the outback.

This rhizomatic approach reveals a lot about the two artists’ interests and motivations. It’s not a publication for the casual gallery visitor, but it’s a rewarding one for those with a deeper interest in the artists’ work, or in artistic research strategies. What The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives) also unravels is a sense of the many intersecting communities around these artists, and the urgency of these collective enquiries. Five years on, and the broader questions around genocide and cultural amnesia have only grown more pressing.

As a prominent mid-career artist, there’s no shortage of commentary around Scarce’s practice. These two recent publications, The Light of Day and The Image is not Nothing (Concrete Archives), shift the usual flow, though it might seem like they talk about the contemporary relevance of her work in different languages. One, produced by and for the art world, highlights the singular talent of the artist. The other, shaped by artistic collaboration, focuses on shared concerns across a wider cultural landscape. But both illuminate a body of work that is asking us to consider perspectives that are rarely seen. As Ball writes, “The stories that carry through her work require us to listen to the current moment.”

If you’re interested in reading further, The Light of Day can be purchased from the Art Guide Bookstore. Visit us in store (43–47 Simpson Street, Northcote 3070, open Wednesday – Saturday 9am – 5pm) or online.