Despite the fact that it is the oldest continuing visual culture in the world, Indigenous art was not considered Australian art until the 1980s. So it is with tongue firmly in cheek that a new exhibition, 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art, is named.

The show’s roots were planted almost a decade ago in 2016, when Peter Jopling, the Potter Museum of Art’s board chairperson, invited Professor Marcia Langton AO to curate a major exhibition. The aim was to showcase the University of Melbourne’s Indigenous collection—but Langton found gaps. “There was nothing contemporary, nothing by women, no Western Desert paintings, nothing from the Kimberley, no contemporary Arnhem Land material, no Tiwi work,” says senior curator Judith Ryan AM.

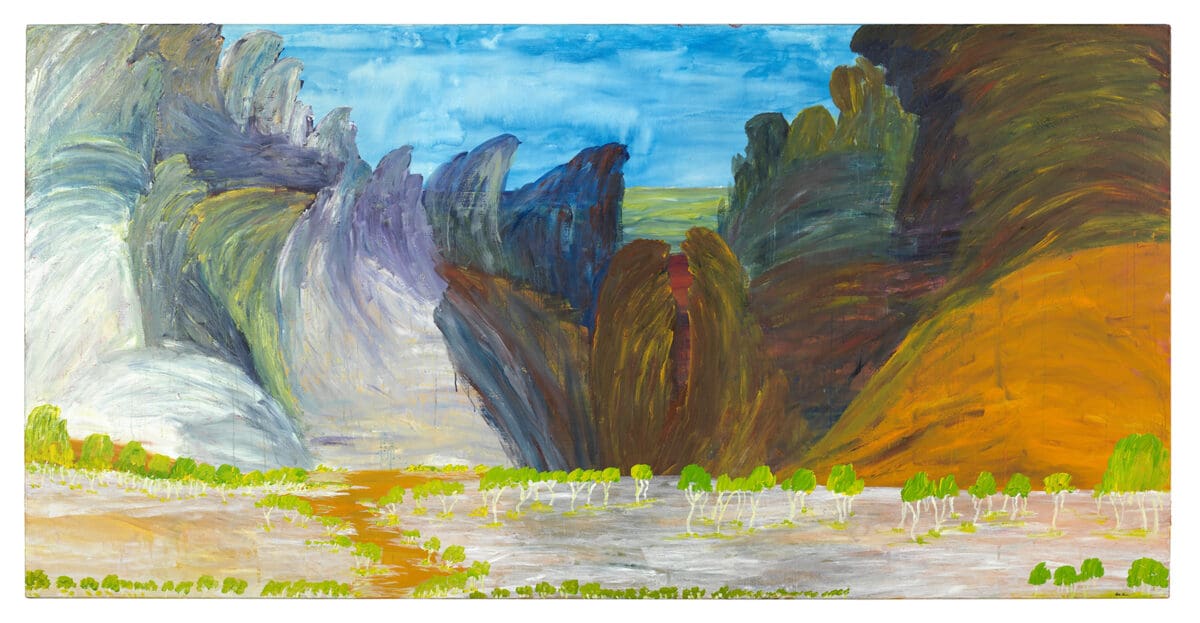

To address that imbalance, Ryan and associate curator Shanysa McConville came on board to find, and commission, works that showcased the breadth and diversity of Indigenous art over millennia. With over 400 artworks (including 193 loans from 77 lenders) and 50 archival items such as letters, ledgers and pamphlets, 65,000 Years covers Arnhem Land to Groote Eylandt, the Central and Western Deserts to the Kimberley. The expansive show is a celebration and a communion. Artists communicate across space and time, including movements and collectives such as Papunya Tula and the Hermannsburg Potters.

“We have these real pioneering leaders, like Rover Thomas and Albert Namatjira, and then we see this interconnected web of artists connected to them, inspired by them, but doing things in different ways,” McConville says.

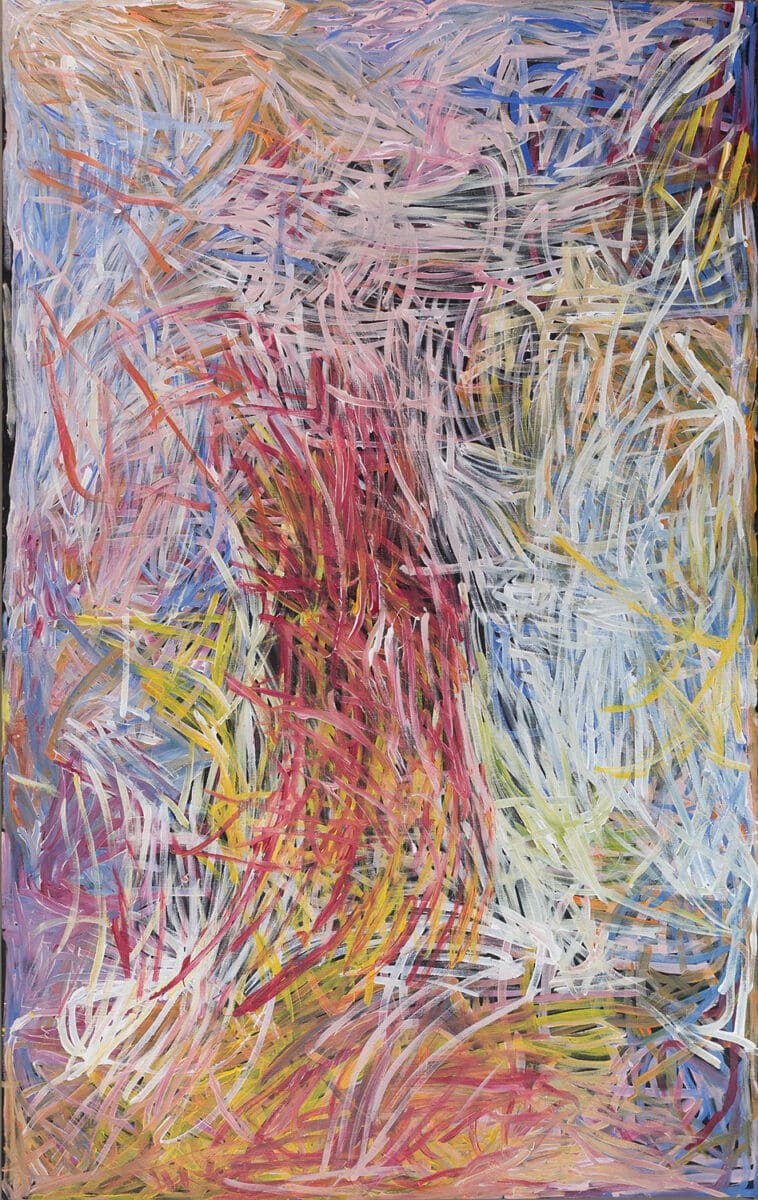

“We have Vincent Namatjira, for example, connected to the watercolour works—[it’s the] same country that they’re from, same connection, same family, different representations of Country. We have sculptures by Marlene Rubuntja from Yarrenyty Arltere, looking at that new medium next to works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye.”

Indigenous artists living and working in metropolitan cities, such as the late Ngarrindjeri artist Trevor Nickolls, are also spotlighted. A section of the exhibition physically replicates the city studios where such artists might work. “[Nickolls was] addressing things like Indigenous incarceration and deaths in custody, but working in these urban warehouse environments,” McConville explains.

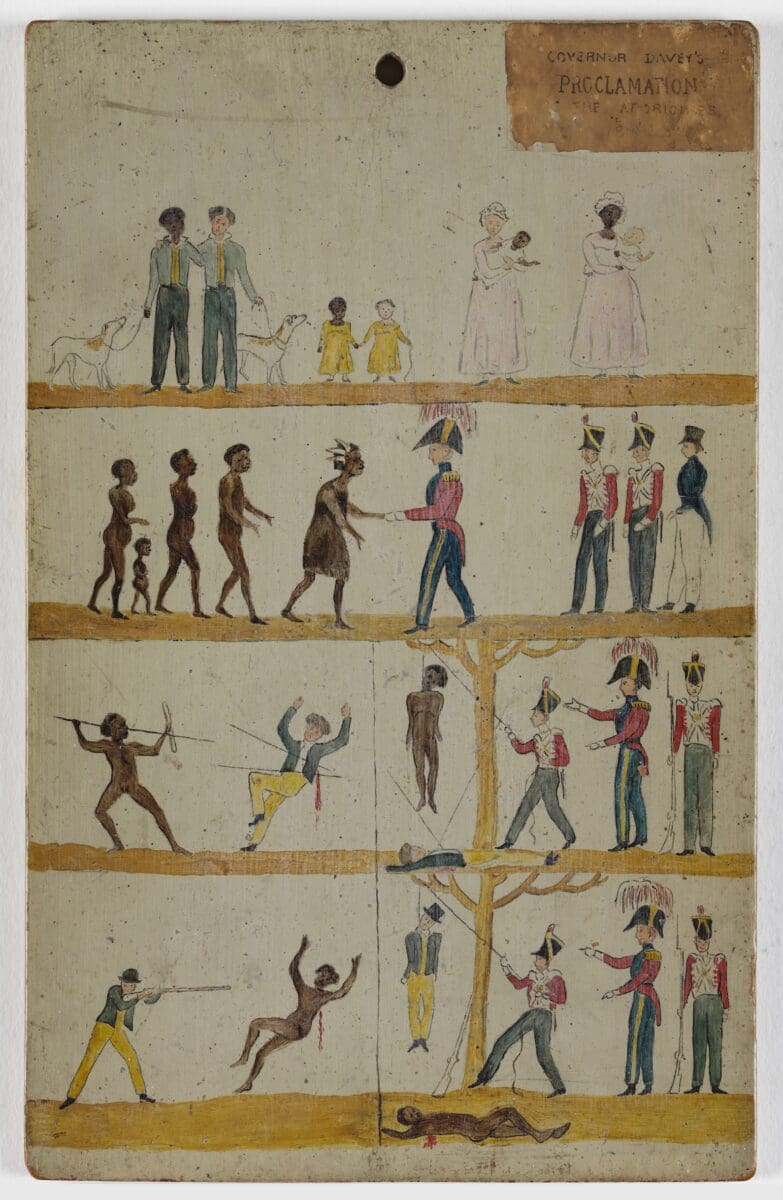

The exhibition has a darker side, too—another aspect of it is “a really tough look at Australian history… like the Stolen Generations,” Ryan says. “It is also looking at the wrongly commenced history of Australia.”

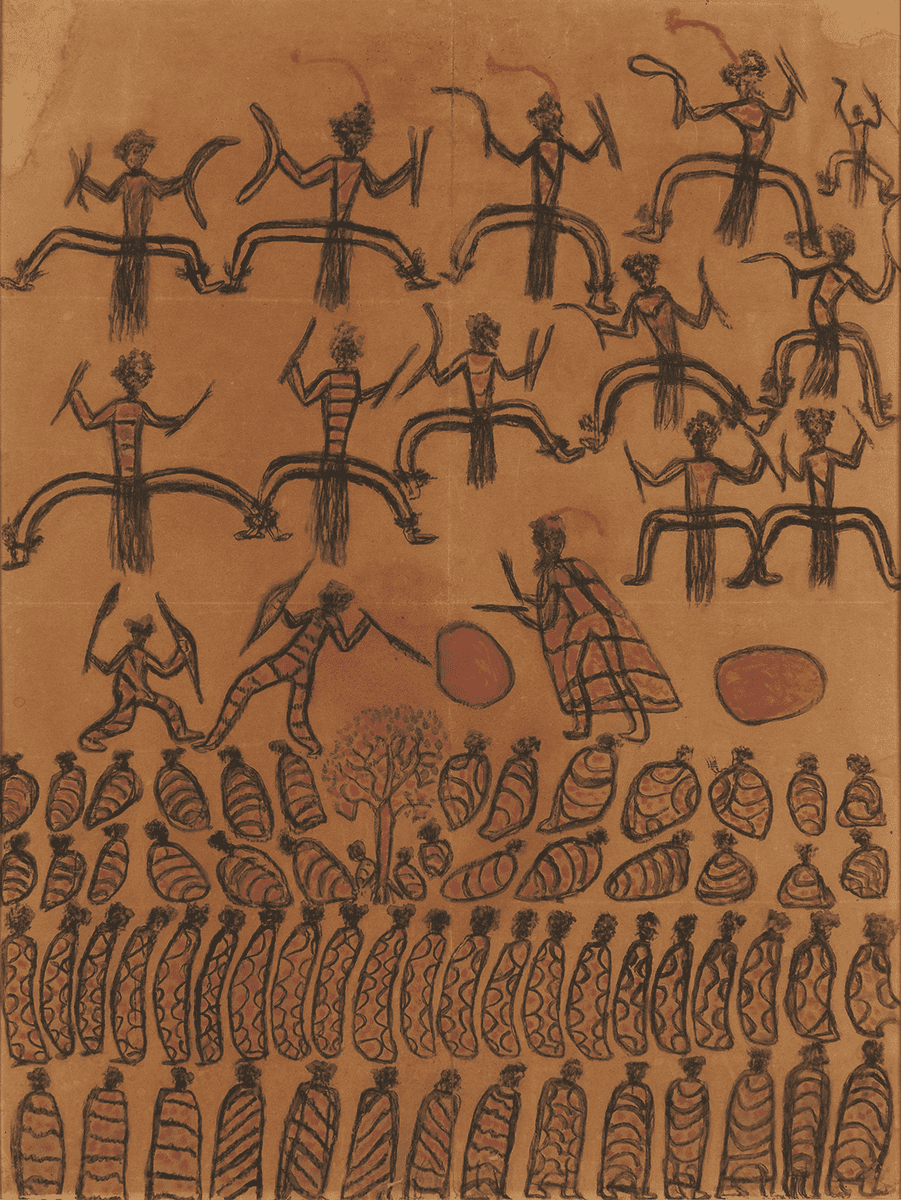

That includes works by Indigenous artists such as Tommy McRae and William Barak, who recorded the arrival and impact of colonisers on their communities; and by non-Indigenous artists such as E. Phillips Fox, Richard Browne, Nicolas-Martin Petit and Thomas Bock, whose works are settler depictions of Indigenous people and land. “The idea is to create historical context and cultural context for all of the works that we are showing,” Ryan says.

Items from the medical history museum at the University of Melbourne, as well as depictions of the tools used to measure stolen Indigenous ancestral remains, uncover the scientific racism and eugenics that were commonly practised. “[We are] putting all of this material out there for public accessibility, for people to be aware of, and highlighting the individuals involved in this practice, such as Professor Richard Berry—and really shining a light on the atrocities committed by these people while they were at the University in the anatomy department,” McConville says. “It’s that material, and then the contemporary responses by Indigenous artists to the same topic.”

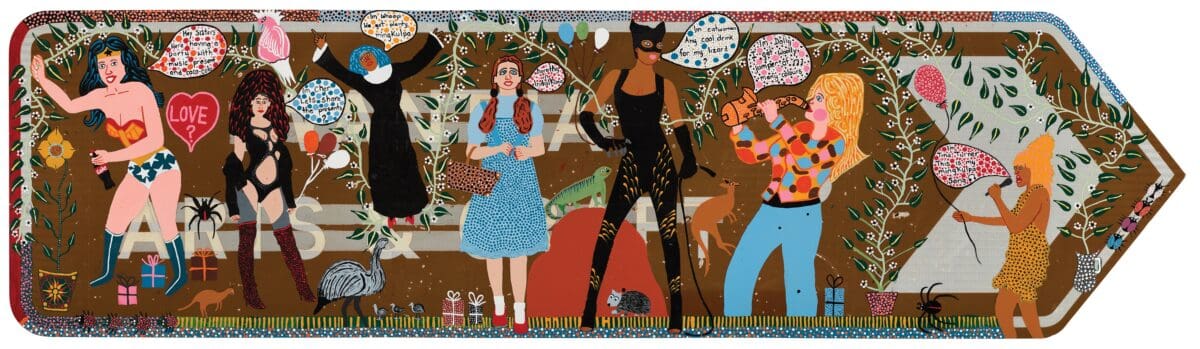

Six new commissions, mostly by women artists, provide a range of perspectives: Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough displays the plaster busts of Wurati and Truganini alongside a nine-channel video work; aunt and niece Betty Muffler and Maringka Burton have collaborated on a five-metre-long painting, Ngangkari Ngura (Healing Country) (2022); Lorraine Connelly-Northey contributes sculptures of narrbong (bush bags);

Trawlwoolway artist Vicki West’s weavings are on display; Kooma artist Brett Leavy creates the Wurundjeri waterways of 1834 through animation; and Dhauwurd Wurrung Gunditjmara artist Sandra Aitken continues the matrilineal practice of poonyart grass weaving with a two-metre-long eel trap.

Aitken’s family tradition was almost wiped out by colonisation when church missionaries came to the area. “The Lake Condah Mission manager told [the elders]… that they were not allowed to pass on the traditional weaving to their daughters,” the artist says. “The Mission was coming into the white people’s way of living, so that is why we lost a lot of culture.”

But Aitken’s aunt, Connie Hart, found a way to secretly continue weaving—the skill survived, and was passed down once more. “Weaving baskets out of the traditional grasses is women’s business,” says Aitken. “Being included in this exhibition shows us how we treasure our ancestors’ cultural heritage.”

The exhibition was preceded by a publication of the same name, in November 2024, featuring writing by over 25 curators, critics and academics. These contributors range from experienced scholars, such as Grazia Gunn and Ian McLean, to the next generation of thinkers, such as Coby Edgar, Tristen Harwood and Eve Chaloupka. Langton, McConville and Ryan also contributed an essay each. “[The book is] going to be a really important resource for people thinking about Indigenous art and art history,” says McConville.

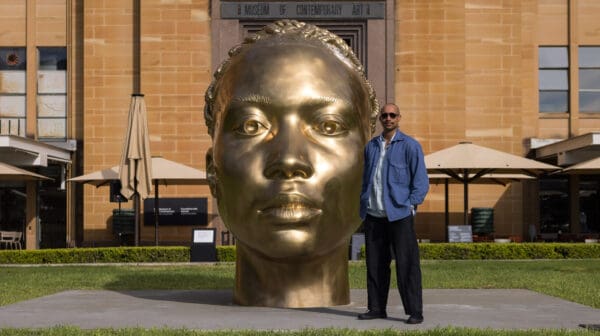

65,000 Years marks the reopening of the renovated Potter Museum of Art, and the curators hope it is a bold opening statement. “We haven’t had an exhibition that takes up the whole space and focuses on First People’s art ever in the history of the Potter,” says Ryan. “I think this sets the agenda—the fact that we are choosing to launch this reopening with such an important exhibition.”

65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art

Potter Museum of Art

(Melbourne/Naarm VIC)

Until 22 November

This article was originally published in the July/August 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.