Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Sera Waters, Trautes Heim Glück Allein in 22,400 acts, 2018, yarn, canvas, found frame, card & cotton, 35 x 45 cm.

Sera Waters, Telling tales on Terry Towelling: Fashioning Locals, 2017, towel, wool, cotton, velvet, trim and bedsheet, 95 x 46 cm.

Sera Waters, Basking, 2016-17, linen, cotton, sequins, tablecloth and handmade glow-in-the-dark beads, 92 x 60 cm.

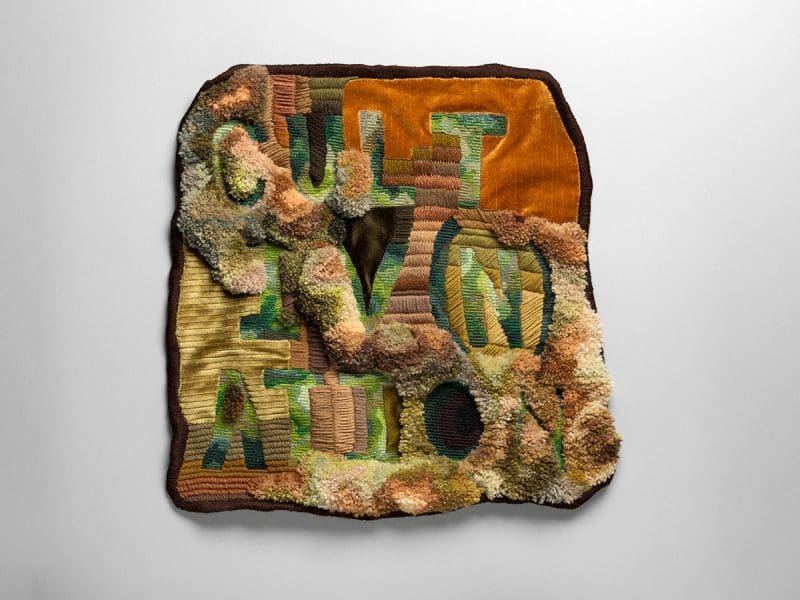

Sera Waters, Banner of Mine: Cultivation, 2017, towel, woollen blanket, trim, glow-in-the-dark thread, metallic thread, cotton and brass poles, 320 x 260 cm.

When writer Sheridan Coleman visited Sera Waters, the artist was as installed in the Art Collective WA gallery in Perth as her unfolding project Limb by Limb. A photograph of her intricate long stitching, depicting a ghostly fallen tree trunk, has been blown up in to a seven-metre wallpaper. Over a 10-day residency, Waters will stitch and affix new ‘limbs’ to the design. The Adelaide-based artist and academic talked with Coleman about dated craft fads, the silences of Australian history, and her current residency and upcoming shows from a squashy velveteen divan, amid skeins of pastel yarn.

Sheridan Coleman: We’re sitting beside this macroscopic enlargement of your sewing, with tightly stitched tree bark and billowy clouds. Tell me about this style of sewing.

Sera Waters: It’s long stitch. The whole project is a riff on Semco Long Stitch Originals kits. You’d sew in to a circular canvas backing, following the outline of a country landscape. There’s something troubling about their nostalgia and denial. They were popular in the 1980s, when Australia was starting to process land rights claims, and yet they seem to yearn for uncontested colonial pasture. Like most of my work, the critique merges with celebration. I have to acknowledge how important those kits were to people like my grandma. She didn’t get the opportunity to pursue her education and I feel like she was expressing some idealised or rewritten past with these images. They are nice, polite, surfaces. I want to know what happens when you start to disrupt that.

SC: This project uses the Semco style, but with an original design.

SW: This design is based on photographs of a strange, fallen tree. The line of the tree, the field, the horizon; each runs horizontally. It’s this idea of a linear process of colonisation, in which fences and boundaries and plantings slowly take over. I’ll be stitching small works to add to it. This one I’ve started is a foot; a limb. It will be edged and pinned here, emerging from the roots. There’s also an arm, an ear, and a strange sunset.

SC: You’ll work here for 10 days straight. What’s that like physically?

SW: I’m doing a very loose and painterly version of a Semco pattern, and calluses are building up, strangely, on my middle finger. It must be how I hold the hoop. It’s also hard to sit for a long time, you can’t underestimate that. I’ll be here day and night, sewing and colliding ideas together.

SC: Lately I’ve noticed how little my mind wanders while sewing. I’m too busy with an onslaught of little decisions about the work. What’s it like for you?

SW: It really is a new decision every moment. I’m working from a printed image, so I’m thinking about how exactly to translate that, how to grade and incorporate yarn colours. I like to be subversive with my colour choices. Pastels are so… nice. I want to see what happens when you use pastels to depict a dead-looking foot.

SC: Let’s talk about this poetic idea of the limbs or the body of the tree.

SW: I was lucky to go on a four-hour drive with my local arborist in Adelaide. He showed me these big old gums, which act as signposts. The Kaurna people used one tree to point the way to Morialta, where there was water. It had carried that cultural weight for years. I regard trees as witnesses to colonisation.

SC: So if a tree is removed, a historical gap is formed?

SW: I’m often thinking about gaps in history, looking for what is not said. I’ve come to understand how important it is to recognise how messy and unrecorded life is. History is so often put into a linear narrative, tidied up or presented by selected voices. I want to draw its knots and tangles into the open, awaken the ghosts.

This gets to the bigger drive of my practice, which is about recognition. The past haunts the present. It makes me so angry to hear politicians say that we can ignore that. People are who they are because of the past.

SC: How do you approach history as an artist? What are your responsibilities?

SW: It was very confronting doing my research, opening the family albums and learning that my ancestors once had Aboriginal servants, young girls. I am part of a body of Australian artists who tell these hidden or coded pasts.

Melbourne-based artist Jacqui Stockdale calls it being a “stone-turner”. We ask people to look at what’s underneath. Sometimes I do feel blind to what’s there. Bill Gammage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth describes some of what can be read in the land: rich Indigenous gardening practices, burn-offs, native wheat silos, eel farms.

SC: Here we return to the land as witness. Does this idea of a material record also inform your use of old materials?

SW: I always use found textiles. You get the marks and enrichment of age, wear and life. In Leaky Sleep of the Sullied, 2017, I cut, stained and quilted my nanna’s old bed sheets. I’m trying to carry history along in the materials. I have no interest in making clean, new-looking textiles. I buy from op shops and people have given me collections that belonged to family members who’ve passed away. I just can’t go into a Spotlight and buy new materials any more. It’s sort of obscene how much stuff there is there.

SC: Are you associated with any traditional textiles groups? Your work requires a strong technical knowledge, but it is not at all traditional.

SW: That sometimes disturbs people, to be honest! I got the Ruth Tuck Scholarship to study at the Royal School of Needlework in the UK in 2016, where I studied very traditional embroidery. Back at home, it was totally subverted.

My particular focus is to look at how everyday traditions contributed to the process of colonisation. Sewing, making a place comfortable, planting flowers: these things enforce new rhythms and claims on place. I often go back to ‘women’s work’ because it’s a record of traditions that aren’t noted elsewhere. I can trace family knowledge and wider histories through pattern, blackwork, cross stitch.

SC: What else is on your boiler?

SW: Genealogical Ghostscapes at Praxis ARTSPACE will be a culmination of the four years of my PhD research. Next year, I have Going Around in Squares at the Textile Art Museum of Australia. It’s an investigation of the grid, which I call a spectral structure, because it lies beneath a lot of embroidery, but also daily life. That will be followed by an exhibition at Hugo Michel about the now-closed Adelaide theme park Dazzleland. It’ll focus on Australian light: the glare, the bleaching sun. I was lucky enough to get Australia Council funding towards my residency and the upcoming shows.

I think of my practice like a novel. The chapters are distinct, but also build and unfold from chapter to chapter, questioning colonisation and its ongoing aftermath.

Limb by Limb

Sera Waters

Art Collective WA

22 Sept – 20 October

Genealogical Ghostscapes

Sera Waters

praxis ARTSPACE

11 – 25 October 2018

Going Around in Squares

Sera Waters

Textile Art Museum of Australia

9 March – 9 June 2019

Dazzleland

Sera Waters

Hugo Michell Gallery

9 May – 8 June 2019