In Mitch Cairns’s enigmatic oil paintings on linen, the many thin layers of pigment intentionally leave no evidence of his brush work. “I have accidentally become a technical painter,” says the artist, bespectacled and feet bare amid the paint-flecked walls of his warehouse studio in Rozelle in inner-western Sydney.

The brushes themselves are, surprisingly, cheap synthetic ones. “I want the paintings to reflect the inherent lack of speed which painting hosts,” he explains, “[but] the brush is a little diagram of how fast the hand and mind are moving at any one time.

“If you see a big swathe of colour being pushed around, that’s painting traction, [and the viewer thinks] ‘I’m in a painting, I’m following the brush mark and I’m looking at how wide it is and where the paint runs out of the brush’. But if there is no brush marking, then you’re looking at other parts of the painting.”

Cairns has momentarily turned off the rotary floor fan that aids ventilation in his sanctum, where he uses just half a dozen colours, mixing them with titanium white for a pastel, opaque quality, challenging himself to see how far a limited palette can take his conceptual, figurative and abstract ideas.

His art, which he describes as “scrim-like” in its depth of field, alludes to literature and poetry, from Italian novelist Italo Calvino to Greek mythology, although he came to reading late, when he was a student at Sydney’s National Art School. Even now, entering his 40s, he doesn’t overthink his ideas, eschewing art theory frameworks and more exercised by how to resolve images.

The title of his new exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Restless Legs, comes literally from a condition—not formally diagnosed—that irritates him in bed at night when he’s trying to read. I tell Cairns researchers speculate a brain chemical imbalance and inherited chromosomal markers might be involved.

“It’s interesting you say that thing about dopamine, because it helps with our bodies coming down before bed, that’s the talk,” he says, weighing the theories, “but it probably does the opposite for me, because I can get highly stimulated by my reading, so maybe it’s more to do with that than any genetic loading.”

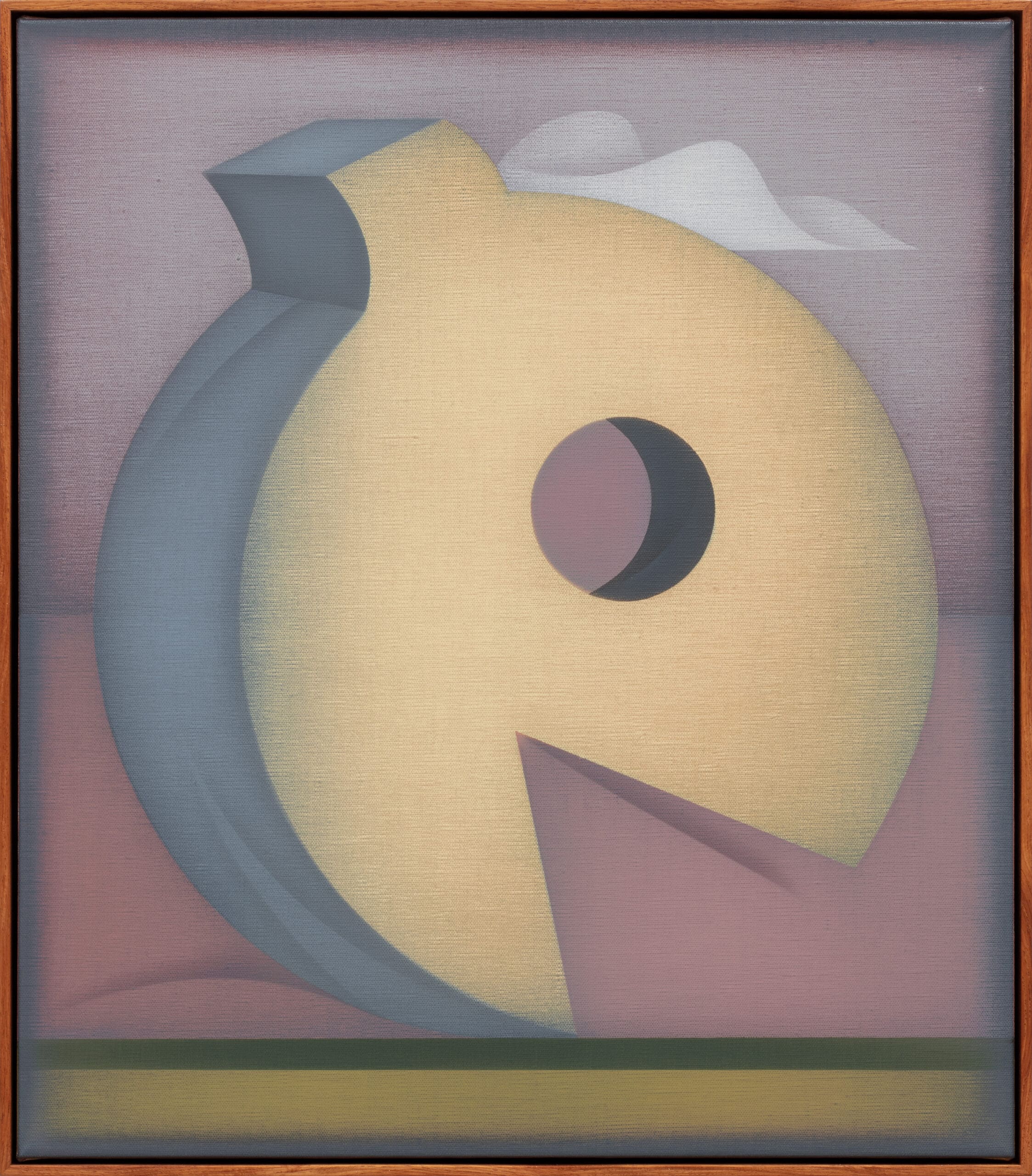

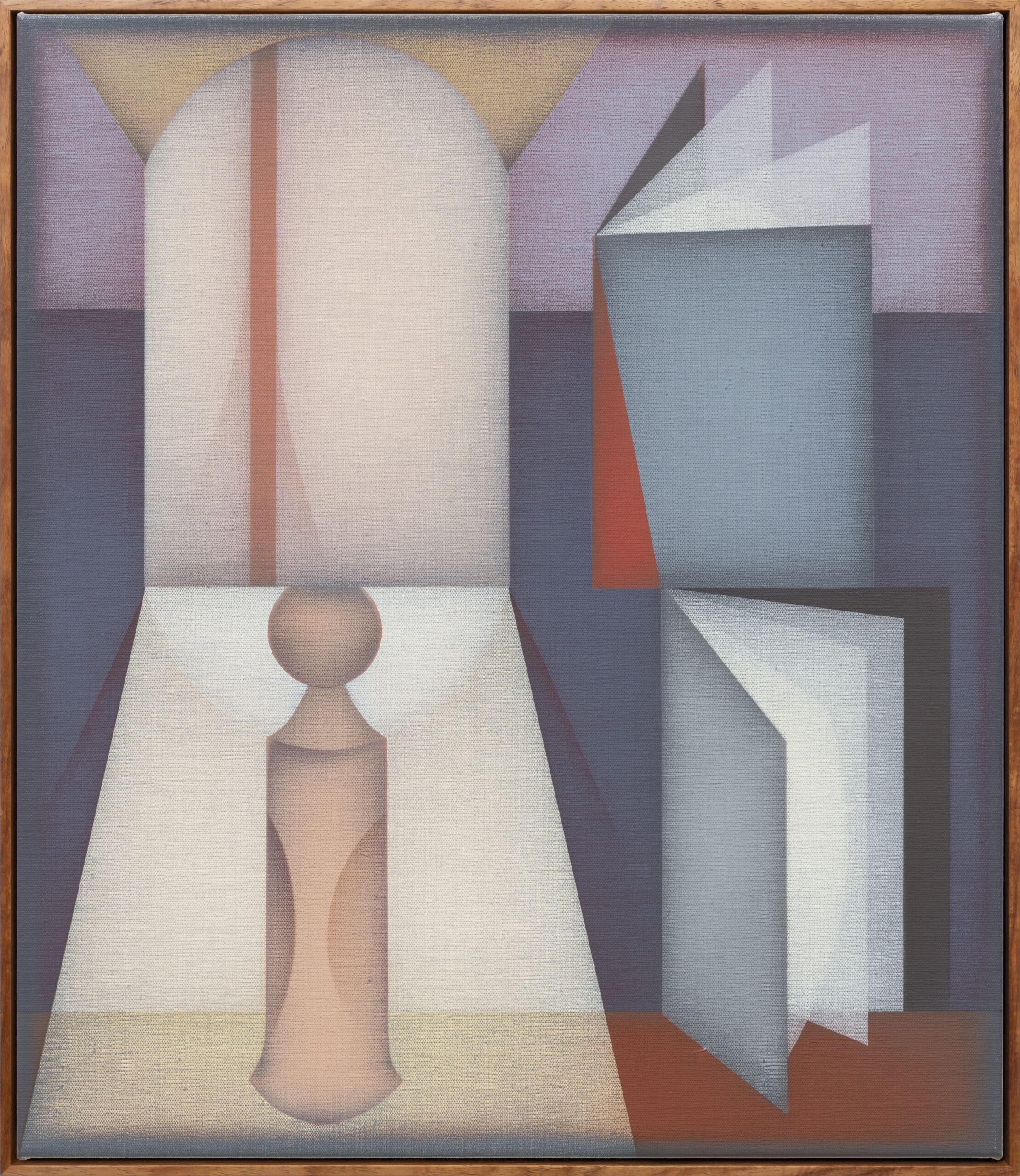

In the painting Self-portrait as a pair of restless legs (2024), white clouds or sheets suggest slumber, while two tall, industrial chimneys evoke the nearby disused White Bay Power Station, built more than a century ago. Indeed, the “self-portrait” concept comes up in a few works, such as the painting Self-portrait as a pair of bookends (2024), consisting of two pink orbs and green stalks suggestive more of a floral still life than the organisation of books.

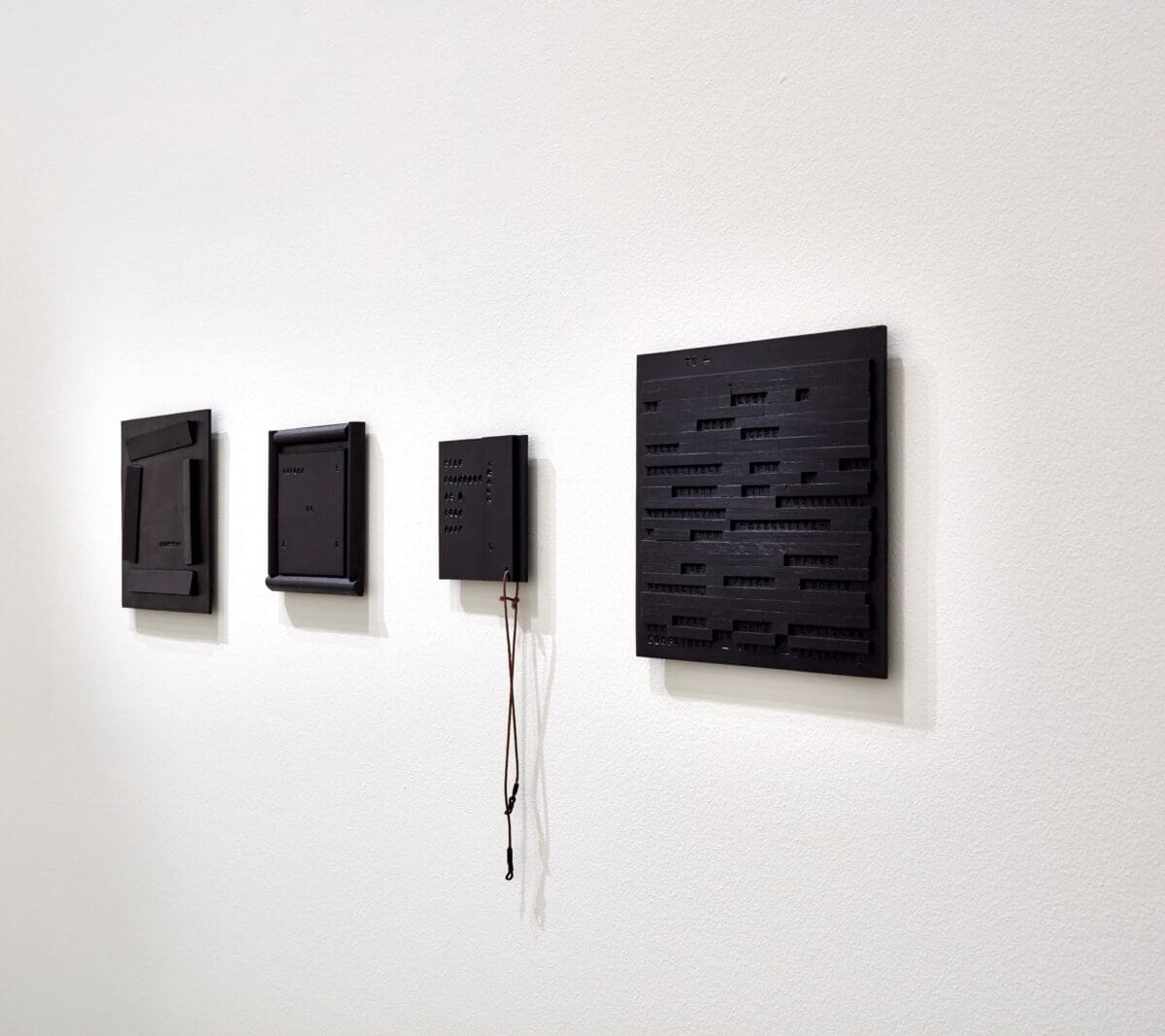

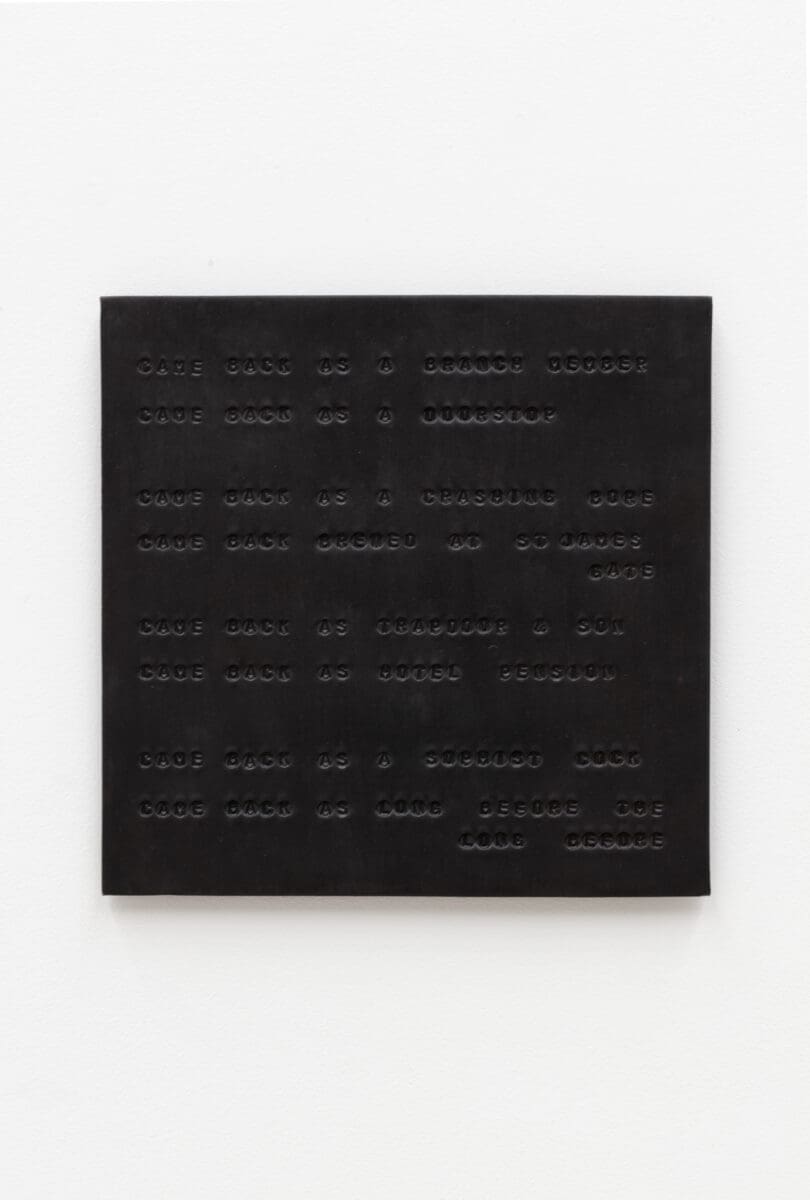

Meanwhile one of several bronze plates in the show, titled Place marker plate (for Roland) (2024) is dedicated to his son Roland and is stamped with the sentence “self-portrait as a bookmark”, a pen strap hanging from the plate. Viewers can contemplate the paintings and plates while seated on a disused telegraph pole, which Cairns included in the show because he admired its beauty as an object.

Is Cairns playing with the question of what constitutes a self-portrait as a result of winning the 2017 Archibald prize for portraiture with a painting of his partner, the artist Agatha Gothe-Snape? “It did come after that moment, not because I thought, ‘Now I’m going to explore self-portraiture’. I think it was just being available to image ideas,” he says.

“I’m looking for lateral ways to approach a painting, and that’s why I often use language. You can look at all the standard bearers and genres of painting, and they can look very much like two-way traffic, but they don’t necessarily have to be that way. It’s just about finding as many sideways into an image as you can.”

On the walls are several paintings Cairns made in the first weeks of 2025, to be unveiled by his gallery The Commercial in Marrickville in July. One big canvas shows five individual shoed feet, inspired by the artist recently getting his sandals repaired; another is an aerial view of spilled fruit, inspired by his unpacking of a fruit box.

Of late, Cairns has dubbed his works “perfume paintings”, in the sense of “something entering the air, a sensory acknowledgement”. Perhaps, he says, the term was also inspired by his late grandmother, who founded a skin care salon for men, her labour reflected in his painting 9-5 (2024), on show at the AGNSW, with a candle in the foreground that morphed into a cigarette while he was painting.

Cairns momentarily reflects on his “rubbish Lone Ranger facial hair”, the fact he cannot grow his beard full, yet his grandmother, as proprietor of the Face of Man in Sydney’s Strand Arcade, was mindful he put his best features forward.

“She would send me shaving kits and lotions and potions, and they looked beautiful,” recalls Cairns, always more concerned with the arrangement of an image on canvas than enhancing his own visage. “But there was no need to use them. I just wouldn’t have known how to, I suppose.”

Mitch Cairns: Restless Legs

Wollongong Art Gallery

6 September—30 November