Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

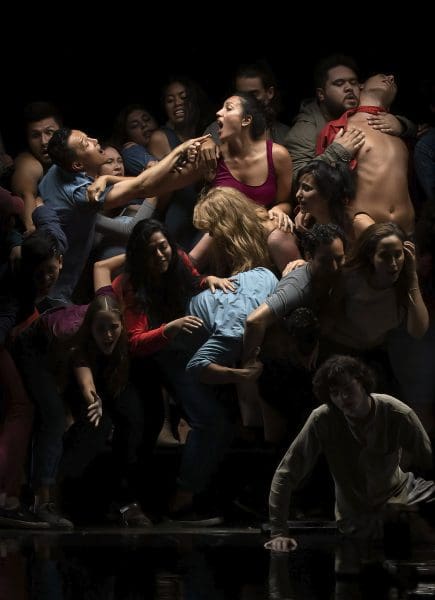

Above a pool of water stands a group of people. Their expressions vary: some throw their hands up in the throes of ecstatic dance; others grasp their chests and mouths, their faces twisted with agony. Some are hidden in shadow, and some sprawl on the floor, crawling as if to a distant salvation. Below, the water ripples; some of the faces are lost in this distorted liquid mirror, blurring into nothingness.

This performative video work, titled Narcissus, is Angela Tiatia’s version of the ancient myth of a man who fell in love with his own image, a story which has endured over 2000 years. The New Zealand-born, Sydney-based artist departed from the singular male figure to introduce a cast of different genders and backgrounds, reflecting the diversity of contemporary Australia and reconfiguring the myth’s message to the increasing precarity of the modern world. While solipsism has always existed, social media has exacerbated the constant centring of one’s own image, so much so that it is unremarkable, even unnoticeable.

“The constant scrolling on Instagram of selfie after selfie made me realise that a single screen can accommodate as many Narcissus figures as I wanted,” says Tiatia. “I wanted to flood the screen or room with more rather than less—to capture a sense of loss of control, or even chaos, many feel within our own global community.

“I also hoped that the cautionary tale of terminal self-obsession would be a reminder to think beyond ourselves in a time where the world needs to think more collectively than ever before, with movements such as Black Lives Matter and the climate emergency.”

The 13-minute work, which will be presented in a floor-to-ceiling display as a part of the National Gallery of Victoria’s 2020 Triennial, is just one example of how Tiatia uses art to show the cyclical and timeless nature of human greed and fallibility. Her 2017 work for the Australian War Memorial, The Fall, recontextualised the Fall of Singapore, which occurred in 1942 when the Japanese military invaded the British stronghold of Singapore. The artist evokes the battle in a modern setting, “to bring the past into the present in a way that reminds us that chaos is always close to us”. Tiatia’s art often explores decolonisation and current forms of colonialism, and she uses bodies—sometimes her own—to challenge the idea that the coloniser is a central figure, and to reject, as she says, the “ridiculous, cruel and destructive” notion that colonisation is a thing of the past.

Raised in a conservative Samoan family, Tiatia was discouraged from being an artist as a child, instead becoming a model in her teens and early twenties. “It was a wonderful and warm environment and value set that is still my touchstone, but there were elements of that world that sought to control women and their bodies,” she says of her upbringing. “When I first worked as a model, in some ways it was clearly so different, but in other ways it had real similarities. They both tended to limit female agency by controlling the image of the woman, and in doing so, dehumanising them.”

The theme of women reclaiming agency over their bodies is also prominent in Tiatia’s work. This can be seen in the 2014 video work Heels, in which the artist uses her own body to confront stereotypes about Pacific female bodies. In heels and a bodysuit, she reveals her malu—a female-specific Samoan tattoo. In 2018’s Study for a self-portrait, which was an Archibald Prize finalist—and extended on the work of an earlier self-portrait, Invisibleness—Tiatia painted herself “in a position of short-term power”. All of these things come from her perspective as a Pacific woman, where the emphasis is on the collective experience rather than the individual.

“I’m not in the habit of making autobiographical work,” she says. “Sometimes I use myself as the protagonist or character within my work, in part as a response to having lost control and agency over how my face and body was projected so publicly into the world. My work talks more about agency and representation when it’s related back to my body.”

These trajectories continue throughout Tiatia’s practice, and the ongoing impacts of the coronavirus pandemic this year have galvanised the urgency of her work: issues such as systemic racism and wealth inequality are becoming more publicly discussed, and the categories of art, body and politics are more intertwined than ever before.

Of the art that will come out of this period of worldwide turbulence, Tiatia predicts that individual artists will have their own creative and personal responses. “Some will find creative energy, using their practice as a platform of protest or a means of picturing a better society, while others may choose to put aside their real or metaphorical paintbrushes and turn to public protest or politics,” she says. “We need to ask ourselves how involved and proactive each of us want to be in order to sustain the changes that we are starting to see.”

NGV Triennial 2020

National Gallery of Victoria

19 December—18 April 2021

Angela Tiatia Solo

Sullivan+Strumpf

Early 2021

This article was originally published in the November/December 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.