Fran Lebowitz has always been rather vocal about the fact that she found Robert Mapplethorpe annoying. She famously recalled, for example, how Mapplethorpe would regularly gift her photographs only for her to then throw them away. “In those days the trashcans in New York were made of metal, and they were out in the street. This was in 1979; you had to bring your trash down to the street, and put it in these metal cans. There were so many of these Mapplethorpe photographs that I couldn’t get them into the can,” Lebowitz told art dealer Gracie Mansion in 2018. Of course, Lebowitz laments this frivolous action now.

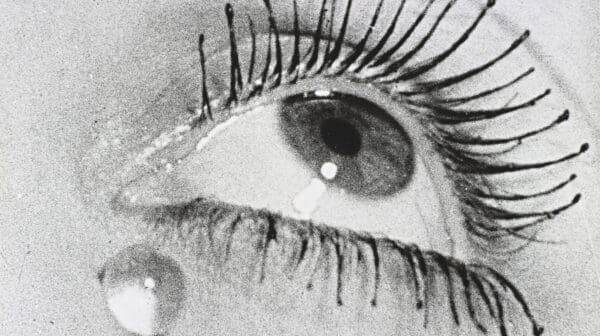

Whether Mapplethorpe was indeed as annoying as Lebowitz claims (see Patti Smith’s Just Kids for the reverse perspective), what cannot be disputed is that Mapplethorpe produced some of the most important and groundbreaking portraiture of the post-war 20th century. In fact, Lebowitz must have seen some form of talent in the photographer. She herself posed for him in 1980. In the photograph, Lebowitz looks over her shoulder towards the camera, a lit cigarette in hand. Clothed in black, her body torso sinks into the background, while her face and hand stand out against the dark. The photograph might be a masterclass in contrast and character portrayal—the sitter’s disdain is even evident in her face.

Gallery goers have the chance to see the Lebowitz portrait along with other Mapplethorpe photographs in Enninful x Mapplethorpe as part of the 2025 Ballarat International Foto Biennale.

While Mapplethorpe is likely a household name for art lovers, Edward Enninful, who has curated this selection of photographs, might not be. Enninful’s background is in fashion. As the Global Creative and Cultural Advisor of Vogue, he has long traded in photography but of the editorial variety. But Enninful is adamant that there is a strong crossover between his work and Mapplethorpe’s. “I am used to images fighting or working together, tension and opposites, or harmony. Things that people don’t expect to go together, finding a sense of serenity within the chaotic,” he stated in the catalogue of a 2024 iteration of the exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris. It is this model of matching images that Enninful has adopted for the presentation at the Foto Biennale. Pairing photographs with different sitters or subject matters, Enninful has sought to create conversations between formal elements of Mapplethorpe’s works.

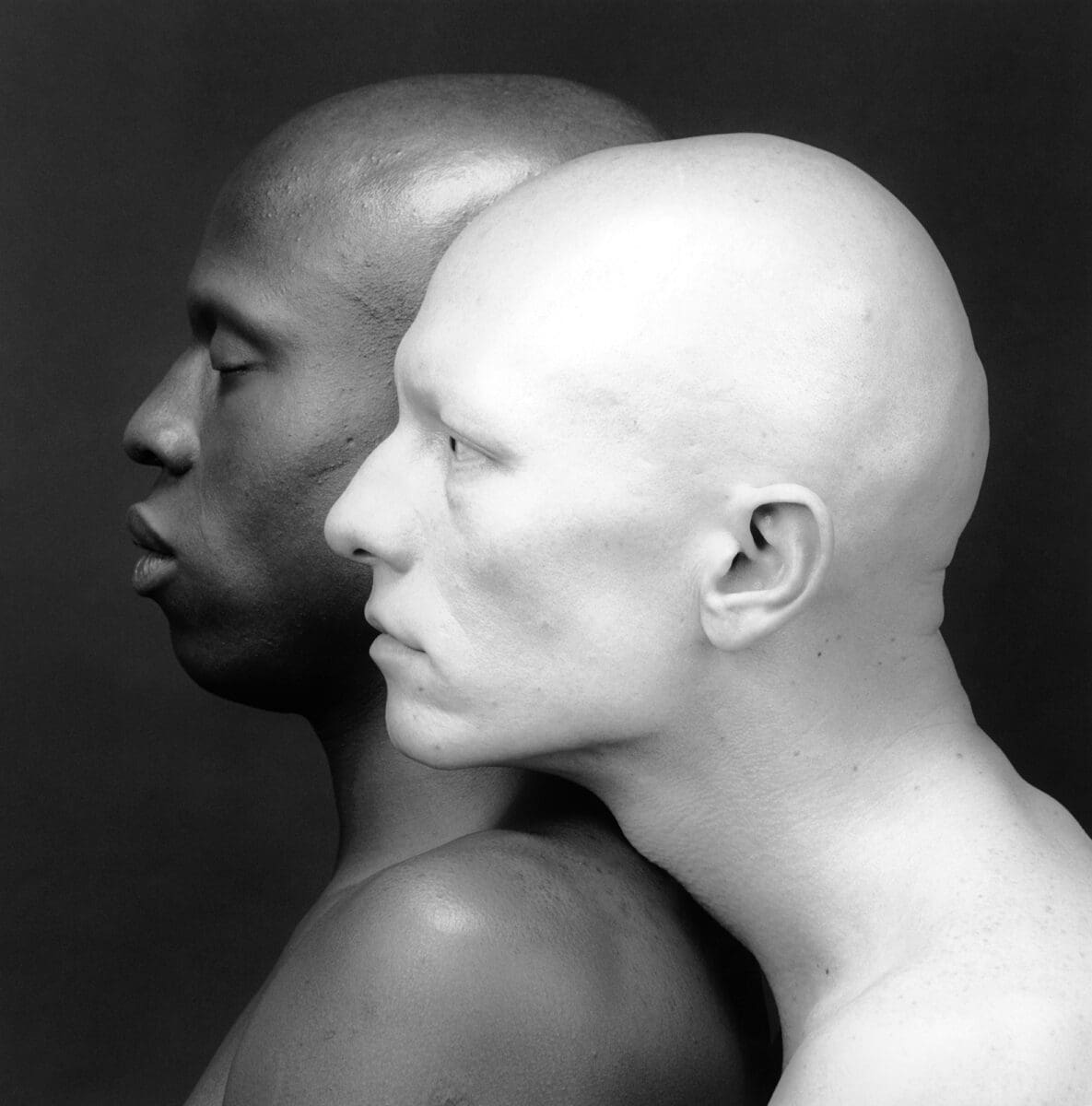

Take, for example, the pairing of two photographs from 1985—Lydia Cheng and Lucinda’s Hands. These two photographs are testament to the way Mapplethorpe expanded upon portraiture—identifying his sitters not by their faces but by their anatomy. The former depicts a woman’s torso, side on. She stretches her arms up into the air and out of frame, making the skin tighten across her ribs. Subtle shadows form at her ribs, darkening towards the arch of her back. Meanwhile, Lucinda’s Hands shows two palms butterflied towards the lens. Contrasted against a black background, the sitter’s fingers appear to mimic the form of Lydia’s Cheng’s ribs.

However, the pairing already reveals an inverse—Lydia Cheng shows a darker figure against a light backdrop, while Lucinda’s Hands offers lightness against the dark. It is this simultaneous eking out of similarities and polar opposites that becomes a common thread in Enninful’s curation.

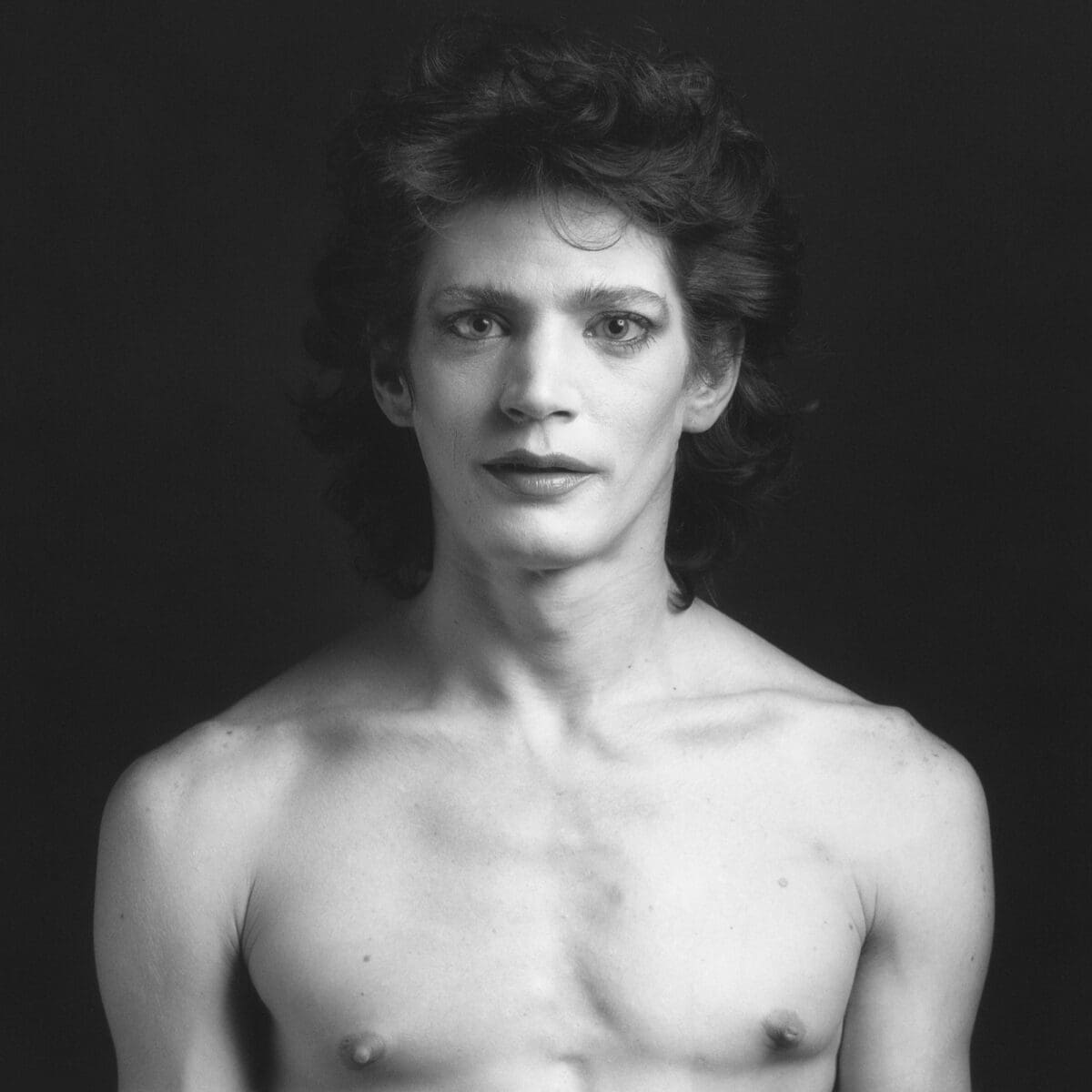

Arguably, it was Mapplethorpe’s representation of androgyny and erotica that were his greatest contributions to the portrait genre. We do see nods to these themes throughout Enninful x Mapplethorpe. Such as Charles Bowman (1980), a homoerotic portrait of a torso that cuts off just above the model’s genitalia. This is paired with Embrace (1982), which shows two topless men entangled in one another. But Enninful has also chosen to focus on representations that sit outside the classic categories of sexy or beautiful. A 1976 portrait of David Hockney, lying on his side, propped up on his elbow and mid-yawn, shows the artist as a sassy and carefree larrikin type.

The picture is said to have been taken on Fire Island, at a gay resort named the Pines that Hockney is known to have visited.

Meanwhile, a 1982 portrait of one of Mapplethorpe’s favourite models, Lisa Lyon, shows Lyon with a sheath of white fabric covering her face and standing in a body builder’s pose to emphasise her muscly physique. This more masculine representation is paired with a portrait of Lyon standing in a wedding gown and clutching a bunch of irises—society’s idea of the height of femininity. Having paired these images together, Enninful emphasises that, in Mapplethorpe’s world, there was no such thing as either, or.

Ballarat International Foto Biennale:

Enninful x Mapplethorpe

Post Office Gallery

(Ballarat/Waddawurrung Country VIC)

Until 19 October

This article was originally published in the September/October 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.