In 2018, when Sebastian Di Mauro and his spouse moved from Brisbane to Wilmington in Delaware, the artist and sculptor was faced with the disorienting process of adapting to an unfamiliar culture and community without the support of family and friends.

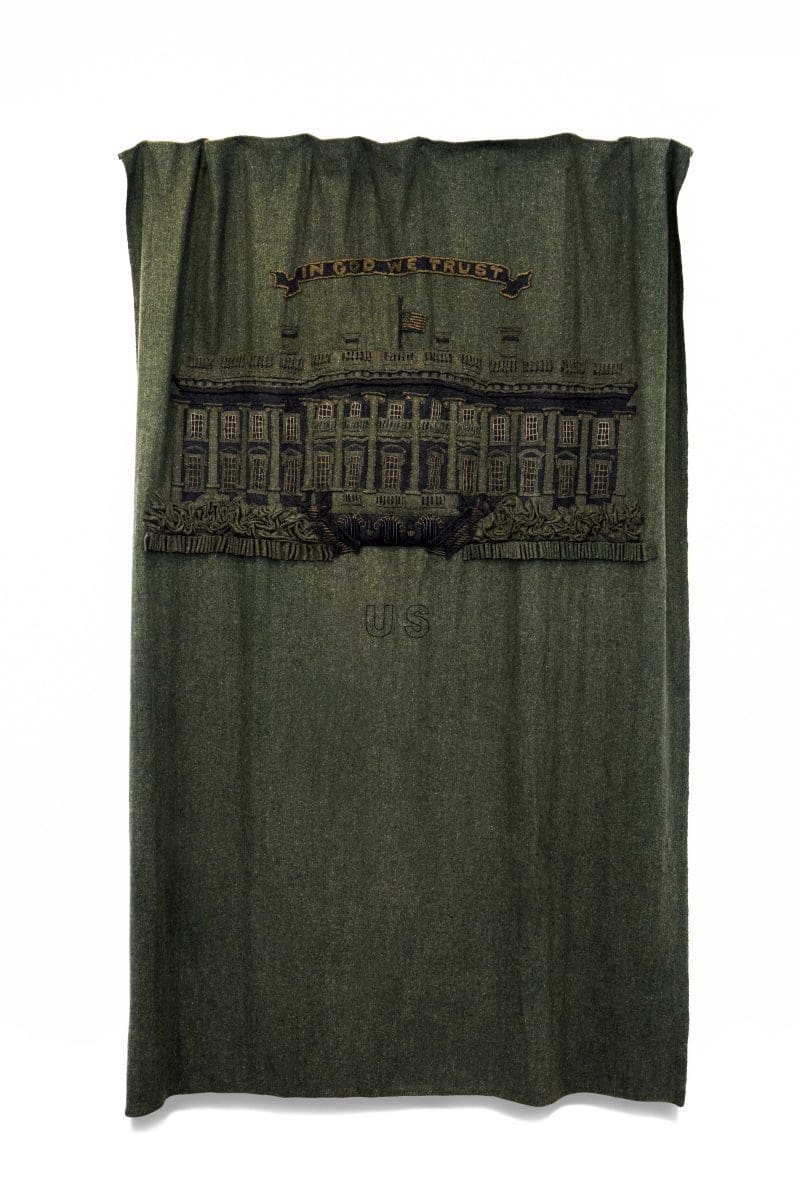

To capture this experience of displacement for his exhibition Greenback at Onespace Gallery in Brisbane, Di Mauro has turned to motifs and materials that have served him well throughout a varied career. Chief among these are blankets, which have been integral to Di Mauro’s work since 1996 when he splayed electric blankets across the walls of Ipswich Art Gallery as part of Skin.

“Metaphorically, blankets reference nurturing, protection, comfort and security,” says Di Mauro. “Everyone can relate to a blanket – as soon as we are born we are wrapped in one.”

Di Mauro’s appropriation of blankets is, however, more complex than solely a representation of warmth and comfort. For Greenback he has repurposed US military blankets and appliqued and embroidered them, ingeniously, with images of the iconic buildings that adorn US dollar notes (hence the exhibition’s title) including the White House, the Lincoln Memorial, the Treasury Building and the Capitol Building.

Often in contemporary art, money is depicted as a negative or destructive force, highlighting inequality, greed and domination (a particularly devastating recent example being Ryan Presley’s Blood Money Currency Exchange Terminal, 2018, at Sydney’s MCA). Greenbackis different. While Di Mauro doesn’t exactly celebrate the dollar, his exhibition is a poetic acknowledgment of how these innocuous pieces of paper have allowed him to transform his life through immigration.

“Money is the binding agent that enables me to survive in the US,” he says, “and it appears to be revered differently here than in Australia. Greenbacks can buy almost anything. They illustrate historical elements that have helped solidify this globally influential nation. These notes are the most used in international transactions and are the world’s primary reserve currency.”

The juxtaposition of cash and the military in Greenback is also intended to examine the complex and overlapping relationship between grand buildings (which represent strength, stability, democracy and nationhood) and America’s historic military might.

“These buildings and monuments are embedded with the history, power and governance of the United States. By working with images of these exceptional buildings I have endeavoured to highlight these characteristics which have been overlaid onto the character of the military.”

Of course, Di Mauro is not unaware of the different shade cast on these themes in light of Donald Trump’s presidency – he emphasises the fact that Trump has increased military funding and intends to continue to do so. Greenback might be said to be questioning whether or not Trump is living up to the supposed integrity that these noble buildings represent.

As well as dealing with politics and history in this way, the exhibition expands in several other directions that reflect Di Mauro’s personal history. For example, he says that the process of creating Greenback has allowed him insight into what his own father and grandparents endured when they immigrated to Australia from Sicily in the early 20th century and were forced to adapt to a wildly different way of life.

Greenback also reveals Di Mauro as a devoted student of quilt-making. The exhibition is in part a tribute to how the earliest American quilts were “intimately connected to the everyday life of the early colonists.” He also quotes American folk art scholar and quilt expert Robert Shaw from his 1995 book Quilts: A Living Tradition.

According to Shaw, “Quilts represent American possibilities and opportunities of freedom, democracy, equality, home, community, and individual expression.”

Greenback is, therefore, a fairly positive, forward-looking show that strongly taps into the artist’s own sense of anticipation about a new life in Wilmington. It also builds on Di Mauro’s previous sculptural works that utilised green artificial turf on a large scale, such as Snuffle, 2002-2003, and Reel, 2010, to name just two. The colour is carefully chosen, both in those works and in Greenback– an exhibition that is, ultimately, about adaptation and belonging.

“I use green in my work often as a metaphor for greener fields,” he says. “My grandparents immigrated to Australia for this very reason. To create a better life for themselves and their children.”

Greenback

Sebastian Di Mauro

Onespace Gallery

3-27 April