Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In a display case in the middle of an exhibition space downstairs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, there is a rich array of extraordinary works created by artists in 1968 for a little-known magazine whose lifespan was brief, yet brilliant. The magazine was called S.M.S., which, in those days, was certainly not an acronym in common usage. For William Copley, the artist who coined the title, the letters stood for ‘Shit Must Stop’.

For the six issues of S.M.S. that Copley managed to produce before the money ran out, he invited an often high-calibre type of artist to produce works that were then painstakingly copied for the magazine and bundled up for distribution. S.M.S. sought to find its own route past commercial art models and magazines, so these fine art reproductions were sent to subscribers in beautiful cardboard envelopes. These days we’d describe all this as ‘boutique’ or ‘niche’, but in those days it was wonderfully experimental.

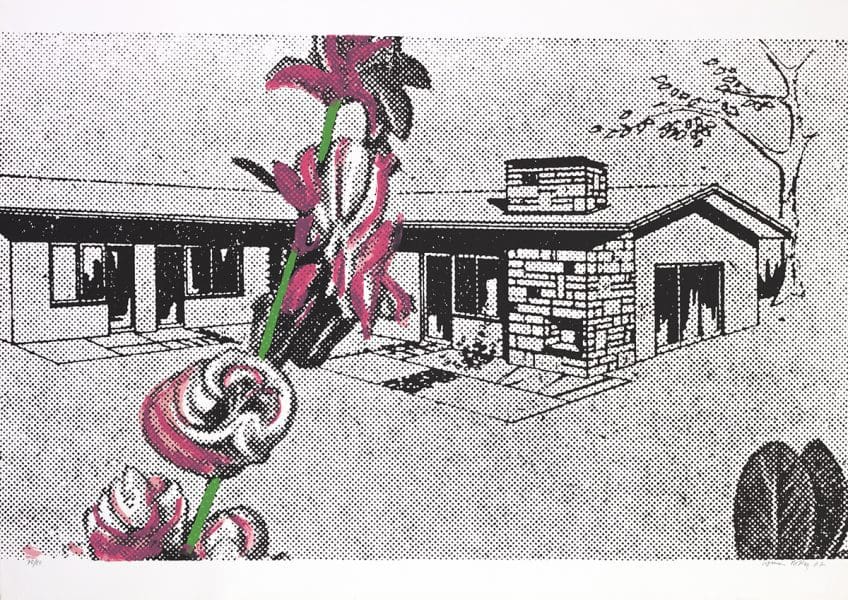

AGNSW curator Judy Peacock adores the S.M.S. works by artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, Meret Oppenheim, Yoko Ono, Claes Oldenburg, Joseph Kosuth and Bruce Nauman, as well as “nobodies and publishers and dealers”. Along with a broad range of other printmakers’ portfolios from the 1960s and 1970s, Peacock chose Copley’s S.M.S. for the new exhibition Yes yes yes yes simply because she liked them. “And I wanted this show to be a lot of fun.”

Connected by era rather than any thematic resonance, the other works in the show include groupings by such luminaries as Corita Kent, Eduardo Paolozzi, Lichtenstein and John Cage. Peacock says this era was rich in interest about the art of reproductions and in the development of printmaking techniques. It was also a fascinating time for the increasing reach and methods of the mass media.

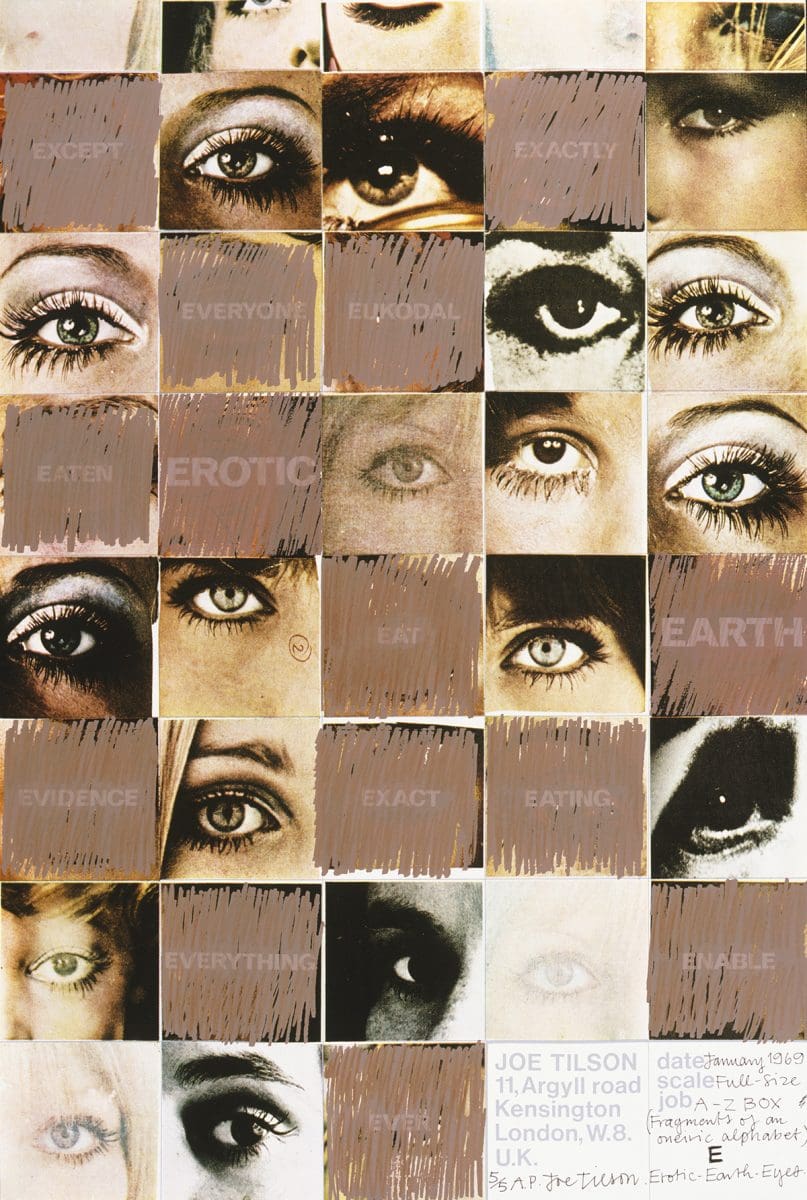

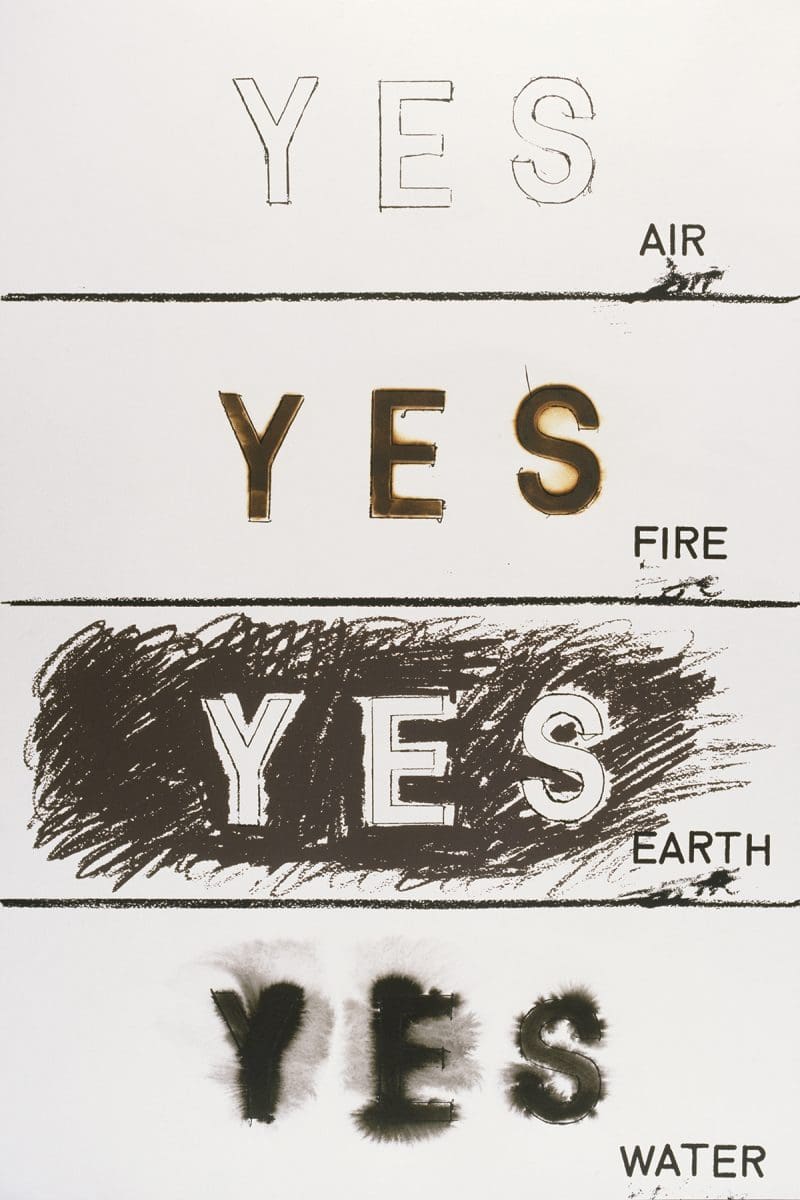

The title of the show comes from a work by Joe Tilson and illustrates the democratic spirit of the era, when these artists hoped to disperse their imagery more broadly through the benefits of printmaking reproduction.

“I have a printmaking background and I have always liked work on paper,” Peacock says. “I like the different mediums in the exhibition. A lot of them are collaged, which you don’t often see these days. It must have been a fun time to be working in printmaking in the 1960s.”

Facing the S.M.S. vitrine in the middle of the room, the four walls have been densely hung with other works from the international collection, which, Peacock says, has an excellent selection from the chosen era. These include the Tilsons, which she describes as more political than the advertising-themed Paolozzis. In a recent interview with The Guardian, Tilson said he now thinks it is a mistake for painters or poets to get too involved in politics “any more than it makes sense for them to get swept up in being fashionable”.

“But we were all trying out new things all the time,” he said. “I remember a serious discussion at the Royal Academy once in the late ‘50s, about whether fine art and pop art could ever get along. A lot of people felt that it couldn’t.”

With that in mind, Yes yes yes yes cleverly gives us the impressively pop-styled Lichtensteins on another wall. They are on display at the gallery for the first time: six different works featuring a bull, which is gradually deconstructed from a real image down to an almost abstract line drawing. In many ways, Bull I–VI 1973, captures much of the spirit and dominant aesthetics of the era, with the grainy photo in I giving way to a new and colourful vision of other possibilities in VI.

Another highlight in Yes yes yes yes is the set of new acquisitions by Kent, a Roman Catholic nun from Los Angeles whose work borrowed from a variety of sources such as billboards, slogans, songs, packaging and magazines, and whose subject matter ranged from civil rights to the Vietnam war and political assassinations.

Like her contemporary Andy Warhol, Kent adored silk-screening and helped raise it to an acceptable fine art form. Even though she returned to civilian life in 1968, 18 years before her death, Kent has only been reappraised as a significant part of the pop art movement in more recent years.

“Her works are wonderful and powerful,” Peacock says.

Yes yes yes yes: graphics from the 1960s and 1970s

Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery

28 July – 23 September

This article first appeared in the January/February 2017 print edition of Art Guide Australia.