Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

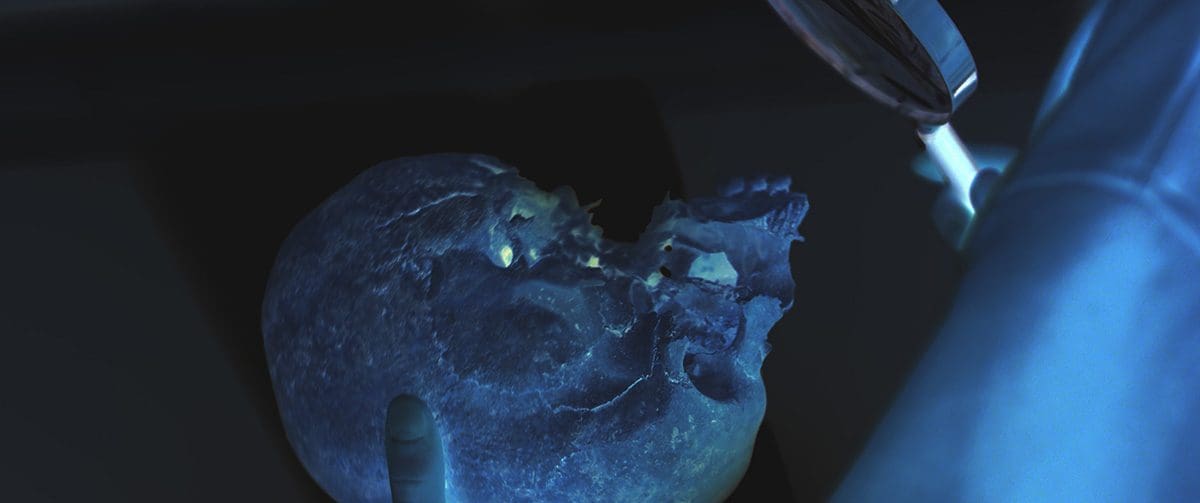

Sam Smith, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, video still.

Sam Smith, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, video still.

Sam Smith, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, video still.

Sam Smith, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, video still.

Sam Smith, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, video still.

Sam Smith, research image of Nyströms cafe

Sam Smith, research image of mineral collection at Brucebo Artist House.

Sam Smith, research image of Viking cairn.

It’s a big jump from Australia to an island in the Baltic Sea. During 2017 and 2018 the London-based Australian artist Sam Smith visited the Swedish island of Gotland as part of an artist exchange organised by Western Australia’s International Art Space. Now showing at the Australian Centre for Photography, the resulting 51 minute video, Lithic Choreographies, 2018, was originally screened as part of a group exhibition which featured 11 artists from Australia and Nordic countries, spaced 3: north by southeast, at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. As Rebecca Shanahan discovered, the exchange shifted Smith’s practice into new and productive fields.

Rebecca Shanahan: Your previous work considered filmic, sculptural and architectural space and time, but Lithic Choreographies is concerned with geological time within a particular landscape, the island of Gotland. How did this come about?

Sam Smith: A central curatorial idea of the residency was to allow the exchange of artists into different landscapes. I didn’t want to bring any preconceived ideas about what kind of work I would make, and understood that engagement with the local community and landscape was important. I made sure to open myself up to what I found when I arrived. There was a residency for research and one for production, with a whole year in between. So the first time I was there, I could spend six weeks exploring and meeting as many people as I could and let the ideas come from the place.

It’s quite a shift. It has some similarities to the work I made before, a video performance work which started to tap into some deep time and geological issues through a kind of architectural filter. So the geological was in my consciousness. The geological landscape of Gotland was very apparent to me when I arrived, because the whole island is made of fossilised coral reefs from around 200 million years ago, and it’s very obvious. You can go to the beaches and look at the rocks and see fossilised activity in the organic matter embedded in the island’s bedrock. And you can see other markers of time, like Viking and medieval history through to the present day. I was struck by how these temporal markers were on the surface of the island, and readable.

RS: You’ve described giving the island of Gotland the agency of a sentient being. How has this been expressed?

SS: It has swung more towards looking at different communities, their relationships with the island and their idea of human and non-human relationships. More specifically, it’s about the relations of humans to stones and minerals – that’s where the title comes from. The material agency of the body of the island is still a prominent feature of the work that manifests through a series of 3D-generated shots. There’s one sequence which is a kind of choreographed dance between a human dancer and a stone. I flew a dancer over to the island and we worked together in an abandoned quarry with a large rock bigger than him that levitates and moves around the space. Dance may be too elaborate a word, but they have movement and an exchange of presences. It’s the idea of how a human and a rock would come together and think through being in the same space.

RS: As an Australian who has been resident in Europe for some time, what did this artist exchange mean to you?

SS: When I think of Australia I think of the vastness, the scale – something you don’t have in most of southern Europe and definitely not in the UK. When you get up to the northern latitudes of Europe, you again start to glimpse the scale, the vastness of landscapes. Obviously on Gotland it wasn’t there, it’s a tiny island, but to me there is an interesting parallel. I’m not sure if it was so specifically about me being an Australian, but I found the landscape very compelling.

I was very open and happy to push my practice into a more community focus of engagement. I had done quite a lot of work with cinematic mediation of landscape in spaces and specific buildings and architecture, but it had never really been about people! With geological time, the interesting part for me was to think about a place’s humans and about how our temporal mode of being is very specific, very finite and small. Hopefully it makes you a bit more empathetic towards the planet.

RS: You brought stylists and a fashion designer on board. What did they bring to the project?

SS: When I was thinking through this idea of time, I wanted to have different visual modes to suggest certain temporalities. So there’s a section shot inside a house from around 1900 and in that section I took out a lot of technology and I didn’t put the lights on. There are sections which are obviously 21st-century mining activities. And then there’s a pseudo-futuristic section where I worked with a group of people from a permaculture eco village. That’s where I brought on the costume designer and stylist. I found two stylists in London and we talked through the idea of a combination of the community’s existing clothing with key pieces outside a normal register of what these people might be wearing. My brief to the stylists was Nordic futuristic activewear: active outerwear that would be practical, things you would wear in the winter working outdoors. We borrowed key pieces from London fashion designer Christopher Raeburn’s collections from the last eight or 10 years. He uses a lot of recycled military fabrics: unisex overcoats and long parkas with an interesting futuristic kind of edge. The dancer is linked into the future mode as well, and wears a kind of flowy cape made from recycled parachute material.

RS: Having made a shift towards community in this work, where to next?

SS: Definitely the environmental focus. It’s something I have been thinking about for longer than this work and finally I have found a creative way to think about our environmental crisis and the way that we are with the planet. I’m thinking about the next work very loosely at the moment, but it might have something to do with marine ecology and coastal landscapes. I grew up in Sydney and New Zealand and now the UK, so I’ve lived constantly in coastal regions or on an island. It has been in my consciousness pretty much my whole life.

Lithic Choreographies

Sam Smith

Australian Centre for Photography—ACP Project Space Gallery

(21 Foley Street, Darlinghurst NSW)

10 May—22 June 2019