Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

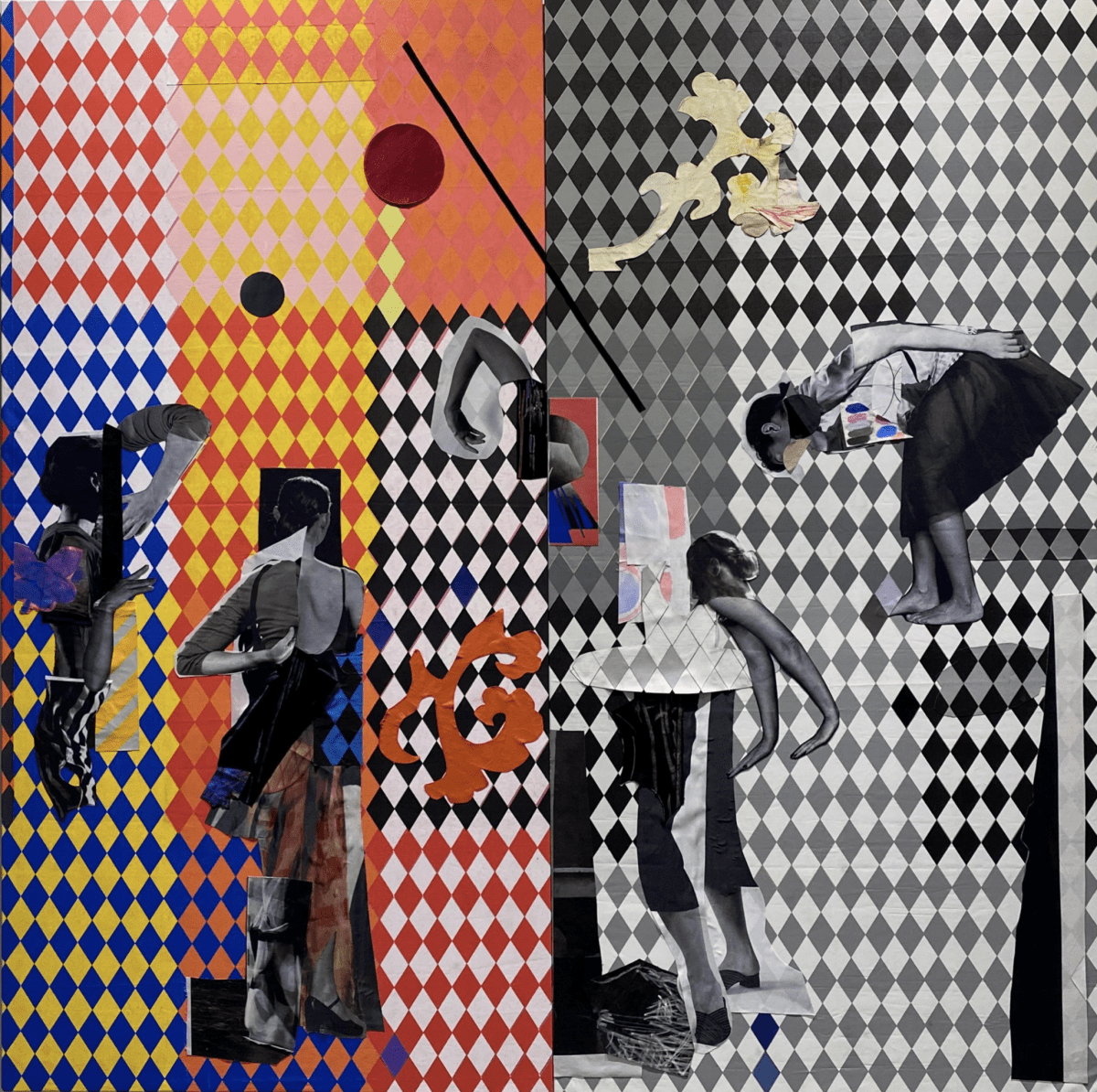

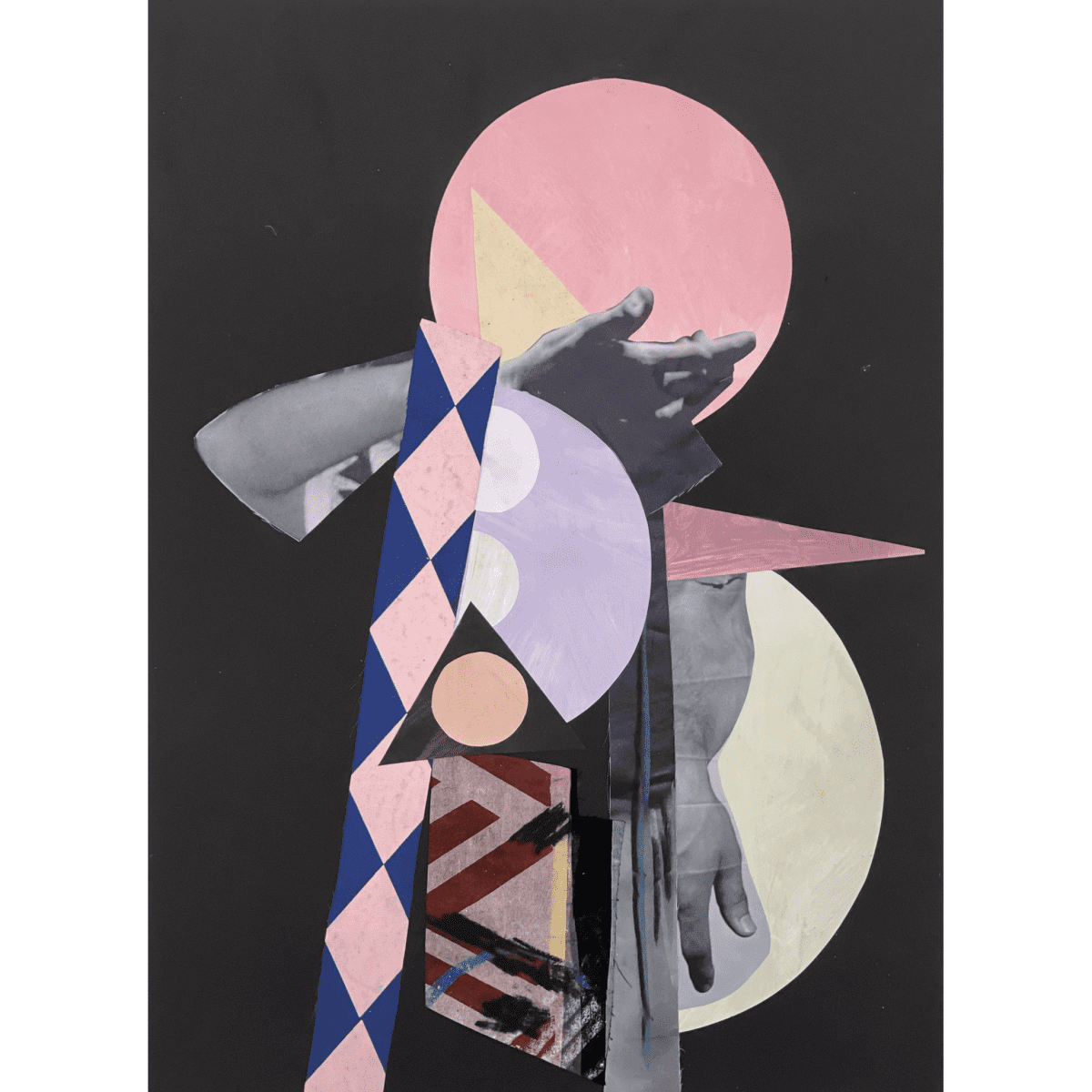

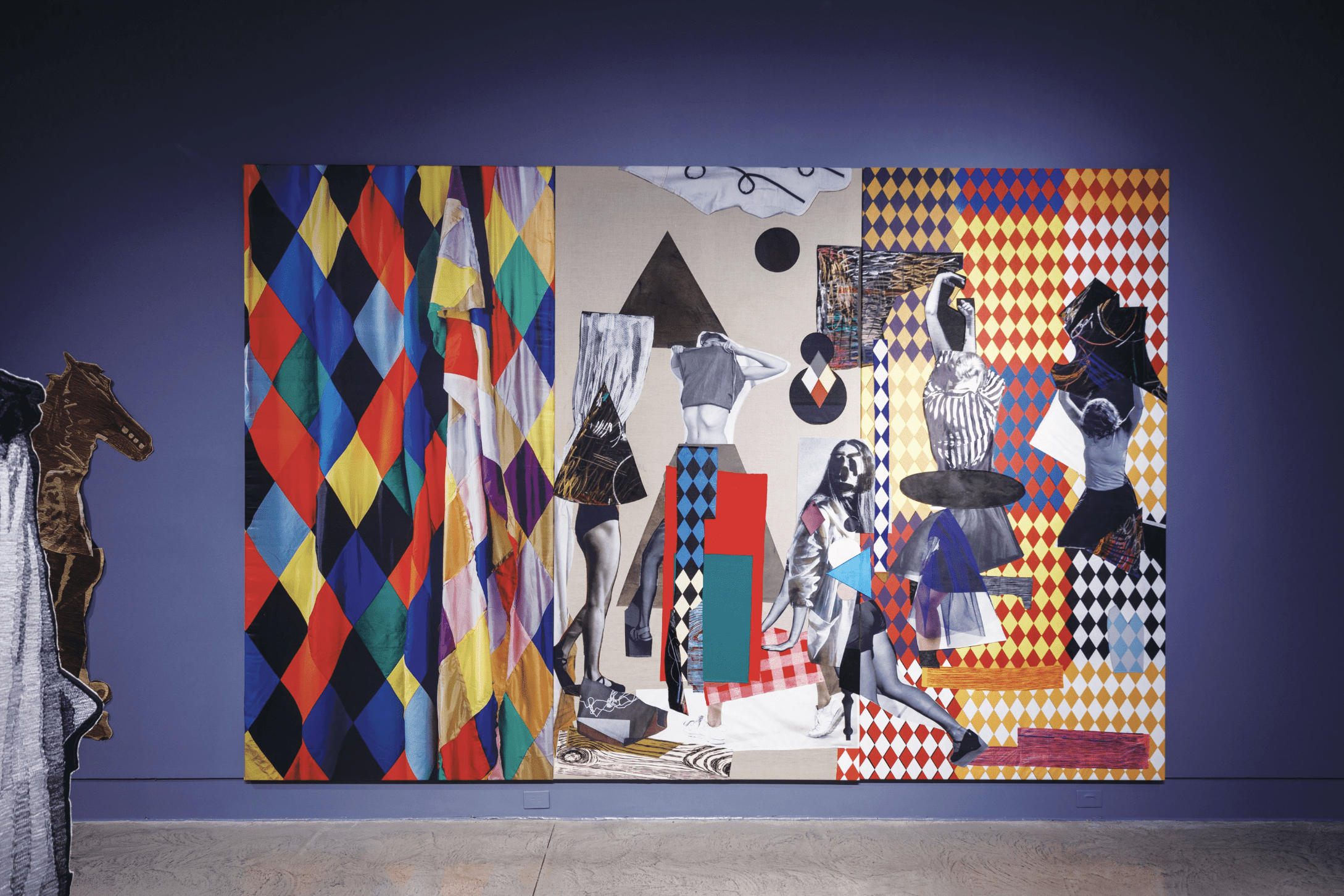

Cutting and reconstructing: for over three decades Sally Smart has gifted us her astounding assemblages, known particularly for her large-scale installations that simultaneously deliver an image that is clear yet fragmented, defying any easy narrative. It’s the visual core of not only image construction, but constructions of identity and gender. Smart talks about the inherent violence and restoration of her work, why structural change is needed for gender equity in the arts, and how her latest solo at Geelong Gallery is inspired by the Ballets Russes.

Tiarney Miekus: You’ve created works questioning gender and identity since the 1990s, a moment when identity politics really entered contemporary art. Does it feel different thinking about those questions today?

Sally Smart: No, not really. I think because I’m different and because the early practice was when I was a student, so it was more theoretical in study. But previous to that was the 70s second generation of feminism and I followed after. Maybe I’d see the difference being greater between the 70s and 90s, than [the 90s] to now. So I’ve lived through [feminist movements] and while the work has changed, I’ve always been very certain that I didn’t need to be making work that had to look like ‘something particular’ to be a feminist. Somebody was reminding me of my early work the other day going, “You were [making overtly feminist works]!” It didn’t seem to me that they were more radical then, than they are now. It seems it’s the same in that the issues are the same: the life lived as a woman are the same demands. Also, I think it was much more theoretical to me then, and now the politics are informed through lived experience— but also in art. There’s more confidence.

TM: I was reading about your great aunt Bessie Davidson, a painter who had small fame in the first half of the 20th century, and how she influenced your choice to be an artist. But that doesn’t seem to answer why you became an artist?

SS: She didn’t encourage me directly because I was a small child when she died, but my mother had been in her studio six years before I was born. I grew up in the far north of South Australia and it was quite isolated. But I was always wanting to be an artist from a really young age. And with Davidson, there was the idea that you could be a woman artist and you could be, in my thinking, a really famous artist. Because I grew up on the Heysen Trail there were a lot of people making landscape paintings, plein air, but I didn’t want to do that. I had a different idea about what art was—I didn’t know what, but it was not looking at a landscape the way they were. It seemed more complex, cerebral.

TM: What were the women around you like growing up?

SS: I was the eldest daughter of four girls and we would do things on our family property. My mother was active in the home but also in the community. There was a lot of work on the property, so we did that: rode horses, motorbikes, drove sheep and cattle. We were young women doing that, until I went to boarding school— and in between I was always wanting to get more paint and brushes, and make more art.

TM: Having now thought and created so much on gender and identity, was there a moment when you realised the construction of these things?

SS: It was at the VCA (Victorian College of the Arts) in my post-graduate year that I looked to literature as a way to progress my thinking, and make works determined to look at constructions of identity—and to make that my project. I created a series of works called X-Ray Vanitas and they were personages of women, with the details of their identity represented through painted, collage like elements. I was working both technically and conceptually to reinforce the cultural constructs. Then I went on to making collage cut-outs and using medical metaphors as ways to view these ideas with representations of the body, like using The Anatomy Lesson [an early 1995 collage work], drawing on art history and women’s participation in science and life drawing too.

TM: When you’re making your assemblages, the acting of cutting is inherently quite violent.

SS: Oh, it’s brutal.

TM: But then there’s the reassembling. The image is complicated because both aspects are there. How conscious is it to have the violence and the restoration?

SS: Totally conscious. I’ve developed this work over a long period of time about cutting and my interest in cutting; how conceptually the metaphors of cutting would show in a psychological sense as well. There’s the investigation of ‘delicate cutting’, the so-called term of cutting the body—self harm—and also the scarification and making marks on the human body. I am interested in cutting in art movements. I often refer to this as ‘the politics of cutting’. That’s really coming out of Dada, but when you cut something, the act of cutting is decisive. And I always wanted to show that I’ve cut—that it’s not seamless because I wanted to show the cut as a sign to alter, to change, to shift. It’s also to reconstruct. I did a series of work that was all about darning, and darning as a sign of repair. You show the marks of repair with darning. You see the wound that was there. You don’t lose it. It is very psychological—as an artist I am aware of making meaning in these cuts. Like an unconscious wish revealing and concealing simultaneously. Sometimes it’s to show a history, sometimes it’s to show an aesthetic decision around the cut. And all of the textiles and photographic elements I use are conceptual: directing, in terms of their individual meaning, an identity that comes together in the overall accumulated assemblage.

TM: When you’re making a new work, do you have an image in mind and you use fragments to construct that image, or it begins with fragments?

SS: It depends. It’s a combination really. Like when I was conceiving The Exquisite Pirate [a series started in 2004 on female pirates], I imagine the ship. And then I take the ship apart, if you like, in my mind, and then study the ship and begin ship building. I make all the elements that would go into the ship. I make drawings, but the building happens on the wall with pinned elements. It’s the elements that are constructed individually of printed textiles of wooden panels; elements of painted felt, printed metallic, skeletal shapes, ropes and so on. The whole ship is assembled with pins and these elements. They evolve over time as multiple works are created, and they’re often site specific. I have an attitude of improvisation in this approach.

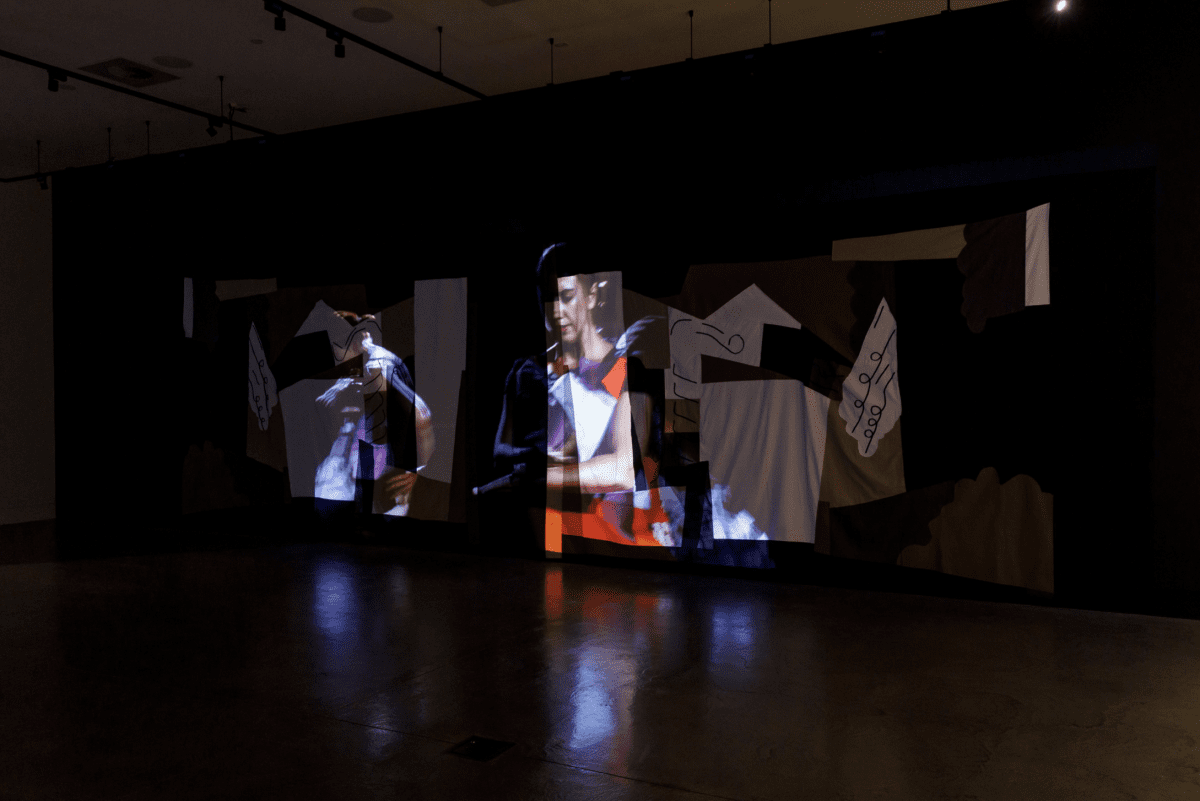

That’s why I’m really interested in dance. There are many connections: the improvised work coming from the process of the work and the place. I move things around with elements. It’s dynamic for me, it’s connected to my own body in the physicality of making: I operate within that liminal space between the element, the space between me and the wall, and the pinning [of the fragments of images], and the movement. There are concerns, aesthetic and conceptual, about movements, gesture and balance, and then there is the psychological: “Why that way, not that way?” And thinking, “What is really being revealed here in this time, in this place?”

TM: Your current show at Geelong Gallery is influenced by the Ballets Russes—a famous, French ballet company active between 1909 and 1929, known also for their brilliant costumes and set designs. What captivated you about that?

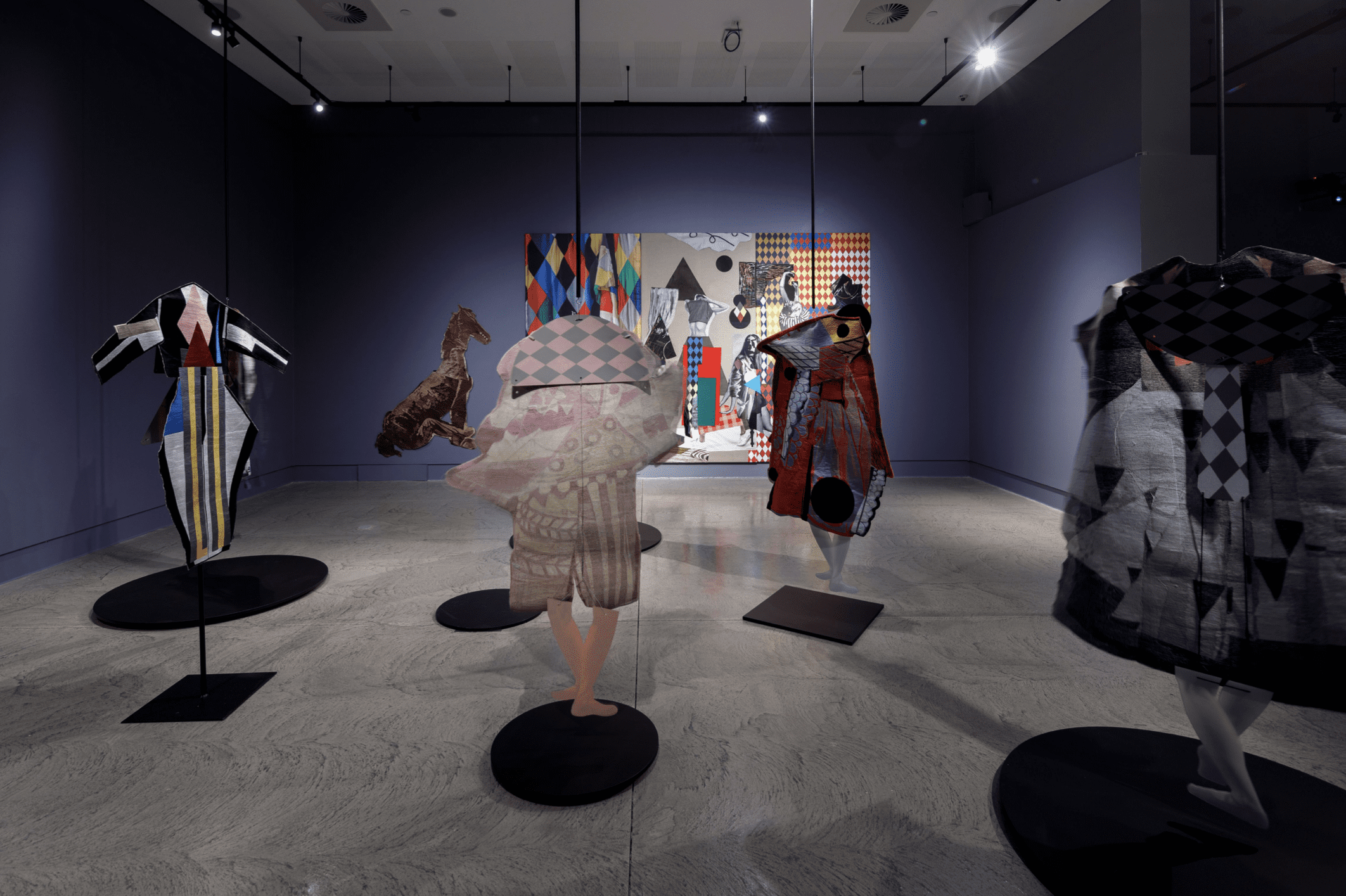

SS: I was aware of the Ballets Russes as a young artist and about the collection of costumes in the National Gallery of Australia. I was interested in them as artefacts of performance. It was the performing objects of the Dada artists that had interested me, especially as there were a lot of women artists involved in early 20th century avant-garde performance. It’s why I was attracted to that period, and their cross-disciplinary practices as well. I began a decade ago to combine performance and dance content in my work, also being influenced by Martha Graham [an American dancer and choreographer]. The intersection of dance and visual artists in the 20th century, and of course the Ballets Russes with their unique combination of art, fashion and staging, have become increasingly influential in my work. I had been thinking about an idea that had started years before with a question I had posed to [NGA director] James Mollison, because he had acquired Ballets Russes costumes for the National Gallery collection. I asked, “Did you ever find in a costume, a fragment of a Picasso costume with an element of a Sonia Delaunay designed costume, like remnants of the two together?” Of course I was thinking of collage like I always do. And he said, “No, they didn’t.” But sometimes they found different elements for sizing, and I’ve since learnt lots more about what layers and labels they found in the costumes.

When I went back to my studio I wrote down our conversation as a small document, on a piece of paper, an idea that I kept with me for a really long time. I thought, “Oh, one day I’m going to work on this somehow.” It took about 12 years.

Through the combination of an introduction to Indonesian artisans and making digital collages I experimented with fragments of original costume documentation—to use as the source to collage disparate elements of Picasso with Delaunay. I also created new combinations based on many of the original costume images through this process. When the finished embroideries were made I was very interested to see if they could be performed. This was the beginning of years of new work.

The Geelong Gallery work is based on reimagining the Ballets Russes Parade [1917] designed by Picasso with music by Erik Satie. It was more a play than a dance work, the hybridised and interdisciplinary approach they began 100 years ago interested me. It was also made during a time of global social and cultural upheaval, through war and pandemic—while anticipating and creating new models of making performance, and [thinking about] relationships between the body, thought and cultural histories. There are parallels with our present moment.

TM: I’ve got one final question: you’re currently on the board of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) and you previously held an artist trustee position at the National Gallery of Victoria, and you’ve commented publicly on increasing the visibility of women artists, but also that there has to be structural change alongside things like NGA’s Know My Name exhibition.

SS: There’s got to be structural change.

TM: Do you see that happening?

SS: Yes I do. Certainly a lot more things are happening; there’s more critical awareness, cultural awareness. We’ve been through many waves of change before, but this feels different. There is increasing alignment with social and economic awareness of gender equity issues. In visual art museums the work of women artists must be there to be seen: they have to be exhibited, to be collected, to have texts and books that research and document their work. They have to have their share of the front banners in a museum; the care, the visibility; there should be as many exhibitions [as their male counterparts]. It’s not just that they’re in a group show; they have to have solo exhibitions that represent them in depth and reveal cultural significance. There has been much discussion at the National Gallery of Australia about the need to do this. We’ve done exhibitions, yes, and other projects, but now there is the consideration of structural change that insists on change into the future. And the humanity of it, you know? Women seem to take—when things get difficult—women take the load a lot. It’s a big concern actually with all the latest catastrophes in the world, how it’ll affect women. So that’s why structurally there has to be change to ensure this commitment to supporting gender equity.

P.A.R.A.D.E.

Sally Smart

Geelong Gallery

Until 3 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.