Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

Air. Water. Mirror. Glass. Sugar.

Rosslynd Piggott is drawn to substances that are slippery, liminal. They flow between states, take shape when held. My notes from her survey exhibition, I sense you but I cannot see you, read like a list of ingredients for a spell.

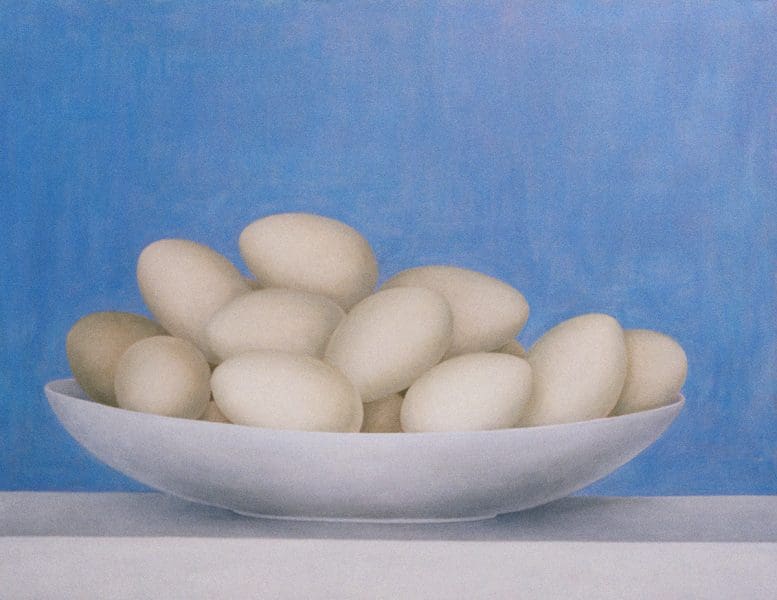

Now open at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Piggott’s survey exhibition spans nearly 40 years of practice. A long-term fascination with dissolving boundaries is established from the very first painting: Glasses of water or A room with four walls of glasses of water, 1986. Moving through the exhibition, glass shifts from painted forms to three dimensional vessels, morphs into abstracted shapes.

Glass is a liquid filled and shaped by breath: it cools and hardens, held in mid-flow, becoming in turn a vessel that gives shape to air and water. Silver-backed, it becomes a mirror, holding everything it faces within its surface.

Wearable (almost). Caught breath. Voids (this I underlined). Pocked and bubbled glass. A depiction of scent.

This is actually Piggott’s second survey at the NGV—the first was in 1998—which is no small feat for any Australian artist. It is gratifying to see a senior female artist receiving well-deserved acclaim, and it feels worth noting given the NGV’s track record of gender disparity and penchant for eye-popping blockbusters. In contrast, I sense you but I cannot see you is a still point, a refreshing drink of water, a series of slow deliberate breaths.

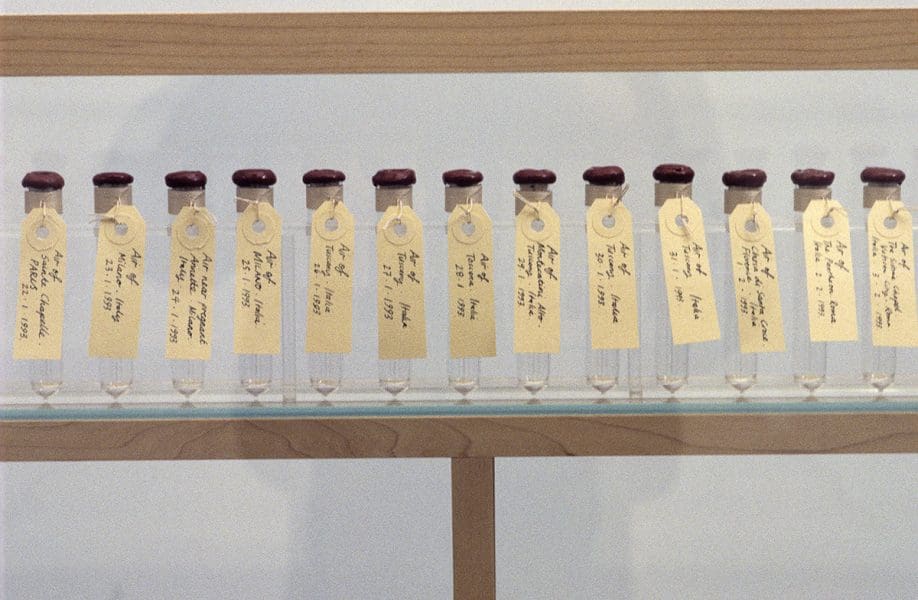

Some of the most captivating works, indeed, are primarily composed of air. Arranged meeting – breath of two men, 1999, consists of two glass vessels blown by different master craftsmen: one in Melbourne, one in Liverpool, UK. Each form holds the trace of its makers, the two men brought together in a single space. Collection of air 2.12.1992-28.2.1993, is a cabinet containing 65 identical glass bottles. Each is meticulously sealed with red wax, dated and labelled with locations all over Europe: this is the air of 65 different moments, caught and held.

In Conversation, 1995, two white nightgowns face each other across a wide expanse, elongated arms trailing towards each other along the floor. A list of words is embroidered down the front of each garment; fine red threads bleed out, connecting the two. Produced during a residency in Paris, each gown bears half a list of opposites: moi/toi,Paris/Melbourne, monsieur/madame.

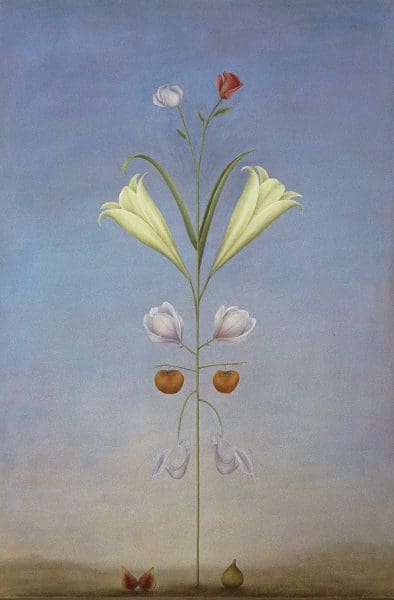

I sense you but I cannot see you unfolds slowly, like the flowers Piggott references over and over. Throughout the exhibition, the lilies of earlier years give way to cherry blossoms and magnolias, reflecting the influence of time spent in Japan. Flowers are captured in video, repeated as pattern, etched in glass.

In Piggott’s most recent suite of paintings, flowers are abstracted into dusty colour fields (we sense but cannot see them). But through titles and dreamy application of paint they hint endlessly towards the hovering scent of magnolias, the essence of a garden.

I sense you but I cannot see you

Rosslynd Piggott

National Gallery of Victoria – The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

12 April – 18 August