Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Please note: due to NSW COVID-19 restrictions galleries in Sydney are currently closed.

Grounded in social justice, Richard Bell’s art is a call to action. It scrutinises settler-nationhood to reveal the corrosive damage made by the colonial state. Through painting, video, text and installation, the Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman and Gurang Gurang artist illuminates systemic racism, land injustice and Blak politics—all with humorous attention to the hypocrisies of the art industry itself, and its manipulation of First Nations artists. Through his iconic body of work Bell asserts Indigenous sovereignty, while reminding Anglo Australia that it lives and prospers on stolen land.

Reflecting on his practice, Bell shares the stories behind five artworks including recent paintings created for Occurrent Affair at UQ Art Museum, which continue to examine racial inequality.

RICHARD BELL: In 2009 to 2011, young Aboriginal people started re-erecting Tent Embassies around Australia in response to government policies towards Aboriginal people. This inspired my response to present an artwork out of the Embassy model. At the time of the original Tent Embassy in 1972, I was beginning my last year in high school and was wondering how we could be so impoverished yet be the original owners of this country. The first rendition of Embassy I did was in Melbourne in 2013 and was meant as a tribute, not only to the people who first established the original Tent Embassy, but also to the young people who had revived the process.

My Embassy projects comprise discussions and papers presented by distinguished guests connected to black and Indigenous internationalism—usually, my friends—most often under a tent, but sometimes under a beach umbrella.

The first Embassy was a success, and invitations to present Embassies around the world started rolling in: Perth, Moscow, Cairns, Amsterdam, Brisbane, Jerusalem, Sydney, New York, Jakarta, Arnhem. They all hosted Embassies. I also successfully staged a Tent Embassy program during the opening and closing of the 2019 Venice Biennale.

RICHARD BELL: After I put a show together in September last year, I just went looking for images that I found interesting. I was very surprised to find an image of Joh Bjelke-Petersen [Queensland Premier from 1968 to 1987] with a shotgun. I don’t remember the name of the photographer, but it was such a powerful image—I wanted to use it straight away. He [Bjelke-Petersen] was such a divisive figure in this state; he oversaw some pretty dark parts of its history. And I remember Joh’s tenure as Premier; I remember as a kid his coup and how he manoeuvred the former leader of the Country Party out of the way. And I remember his demise as well, where he reportedly accepted bribes in the form of cash stashed in brown paper bags.

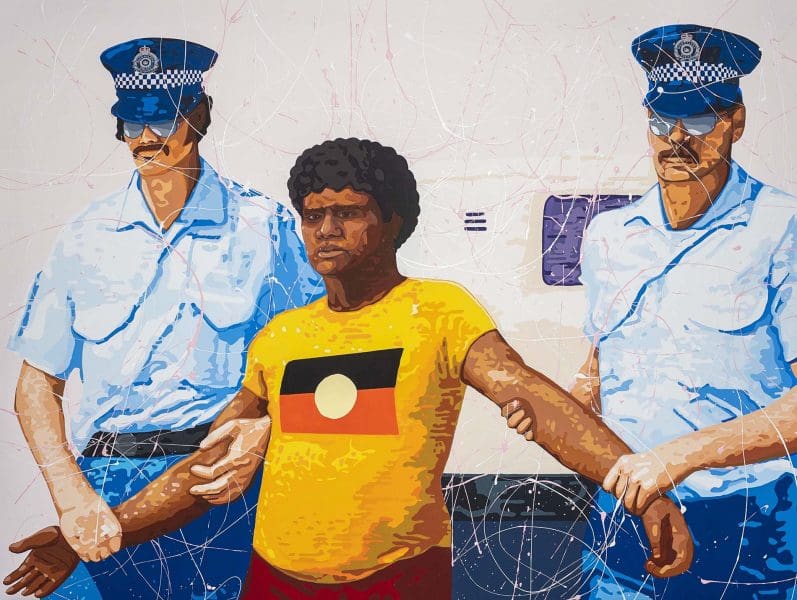

RICHARD BELL: Once again this is from a great photograph, and I’m just trying to do it justice. The reason I love the photograph is because of the defiant look that the protestor has. It was an image from the Commonwealth Games in 1982, and prior to the 80s all police in Australia had to be over 6 foot 2 inches. These two guys were definitely over that, and we’ve painted it larger than life so it’s really imposing. The coppers are looking down so there’s a certain dignity exuded by the young guy.

RICHARD BELL: [This work comes from] three separate, past interactions with Chinese nationals relating to international trade between Aboriginal people and Chinese people. Each event happened 10 years apart, and began in 1972 and ended in 1992.

1972 saw an Aboriginal delegation sent to China shortly after Prime Minister Gough Whitlam had visited. Then in 1982, I happened to be working for the Aboriginal Legal service in Redfern and there was a delegation from China visiting Australia looking at trade. They invited us—a delegation of Aboriginal people—to the South Sydney council meeting. Finally, in 1992 I met a Chinese woman at a trade fair in Brisbane who was interested in trade, also. I was making tourist art back then, as well as contemporary art, and she asked me whether I was interested in selling arts and crafts into China. She said there were more millionaires living in China right now than there were people living in Australia.

I tried to imagine how we could trade.

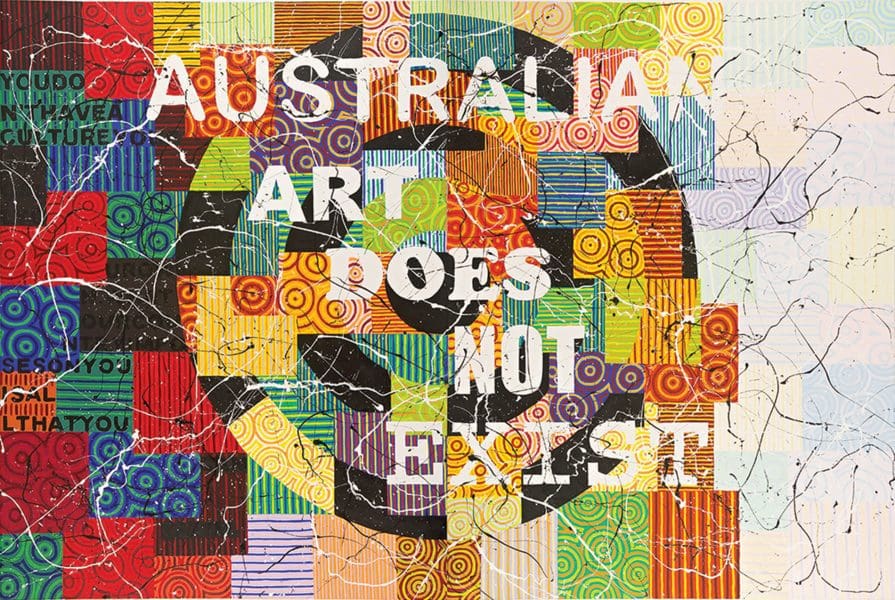

RICHARD BELL: I had a breakthrough from making contemporary art on a regular basis. I did a bit of research and as far as I could see, Aboriginal art outsold Australian art by between five and ten to one. It was five to 10 times bigger than Australian art in measurable terms, and in cultural terms there’s no comparison.

The first thing visiting tourists want to see in art museums in Australia is Aboriginal art, because they’ve seen examples of everything else in other European countries or colonies. Basically, Australian art does not exist outside of the minds of Australians and I thought, “Fuck it, I’ll put that statement out there.”

I’d won the National Aboriginal Art Award with a painting with the text ‘Aboriginal Art is a white thing’ and the next one was ‘Australian Art is a black thing’ and both statements are true. It is indisputable: Aboriginal art is a white thing. It’s presented in institutions that call themselves art galleries but are really just trophy rooms. And Judgement Day was the third one. I came to the conclusion of ‘Australian Art Does Not Exist’ as a statement of Aboriginal ownership of art and culture in this country. It’s an assertion of Aboriginal sovereignty over art and culture in Australia. That’s the reality.

OCCURRENT AFFAIR: proppaNOW

UQ Art Museum

13 February – 19 June 2021

You can go now

Richard Bell

Museum of Contemporary Art

4 June – 29 August

This article was originally published in the March/April 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.