Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Léuli Eshrāghi’s work is about rewriting the script. An artist, writer, researcher and curator, Eshrāghi rejects colonial structures and norms to shift the focus onto the rich cultural histories of communities of colour. “My work is always about projecting into futures of wellness away from the colonial present,” they say.

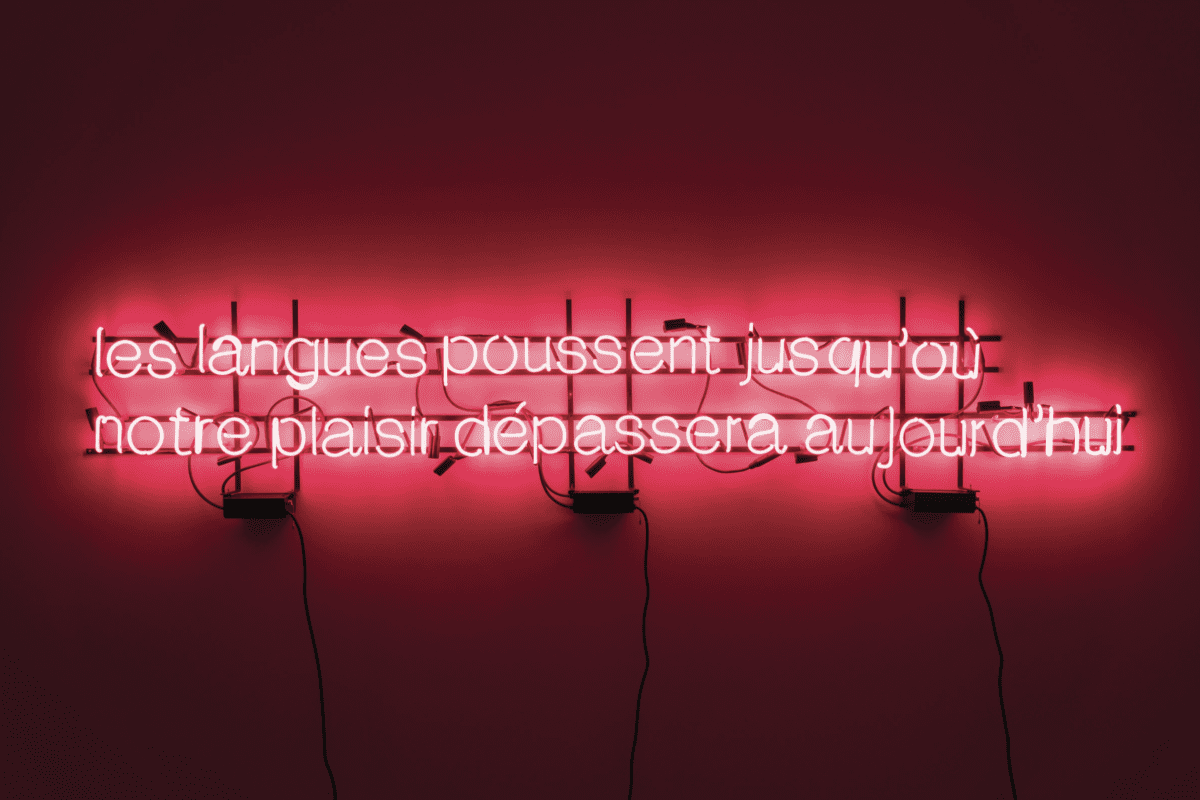

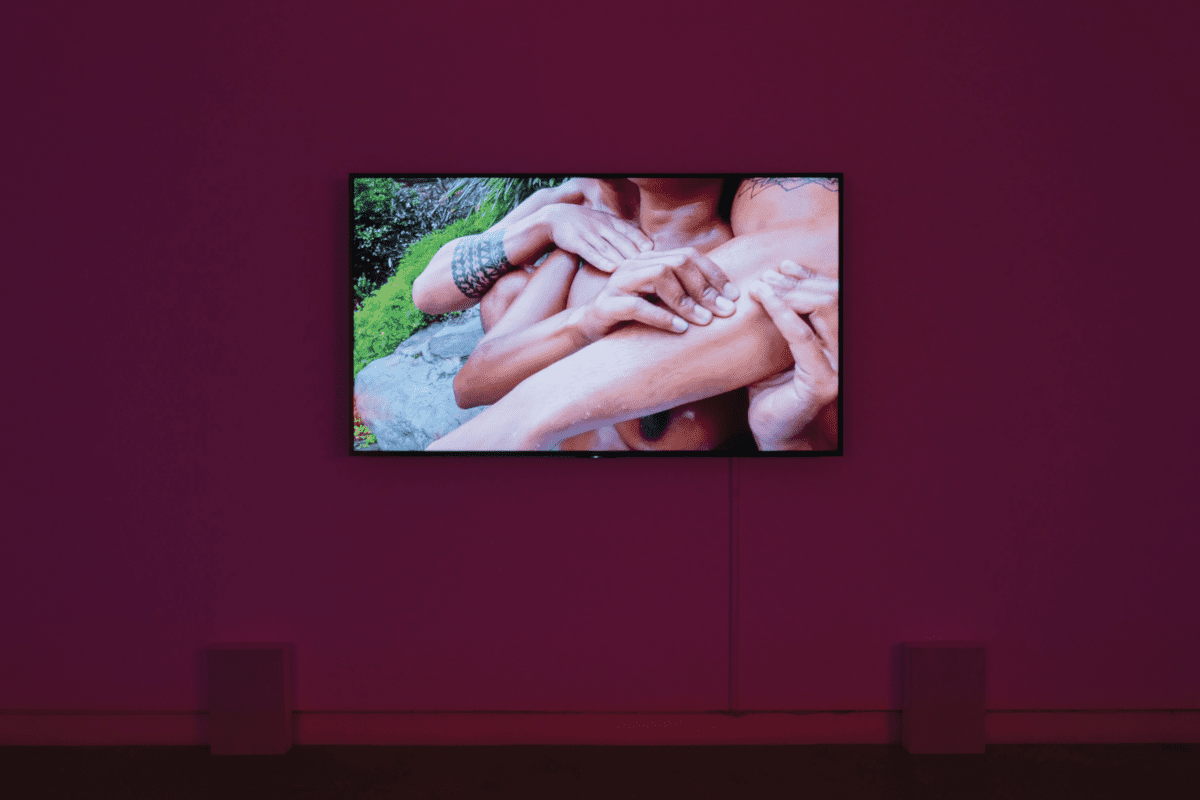

Eshrāghi, who is of Sāmoan, Persian, German and Chinese heritage, and uses the gender-neutral Sāmoan pronoun ‘ia’, creates in various mediums, including performance, installation and video. One of the most unique aspects of Eshrāghi’s work is the use of barkcloth: a customary practice across Oceania in which paper mulberry bark or hibiscus bark is beaten, stretched and dried. In what they describe as “a continuum of cultural practice”, Eshrāghi takes an inventive approach, as seen in their 2020 video work TAFA ( ( ( O ) ) ) ATA, which combines barkcloth with animation.

Eshrāghi’s work also reflects on the pressing issue of climate change from a diasporic perspective, explored in works such as Expanses, 2021 and the 2017 collaborative performance work Lukautim Solwara (look out for the ocean). And it’s this topic that will be explored in Oceanic Thinking, the first of multiple years of exhibitions in UQ Art Museum’s Blue Assembly project. As curatorial researcher in residence, Eshrāghi will work on an online publication to accompany the artworks, furthering the idea of not only decolonising the issue of climate change, but also the activism surrounding it.

“Part of the problem is seeing it in black and white, when really there are so many different ecologies around the ocean, different understandings—a lot of oral histories here and elsewhere in the world,” Eshrāghi says. “I really reject the term Anthropocene, and rather think about it in cycles of time.”

Eshrāghi mentions Samia Khatun’s 2018 book Australianama as an inspiration for their approach to their own work, particularly with the UQ Art Museum’s Oceanic Thinking and their upcoming curation of TarraWarra Biennial in 2023. “It’s a Bangladeshi-Australian historian’s accounts of Australian colonial history entirely from diverse Aboriginal oral histories and South Asian language texts—she didn’t use any English language original texts,” they explain of the book.

“I want to de-centre English as much as possible by commissioning texts in different Indigenous languages and POC languages from around the world. I just really think, using English everywhere all the time, we’re flattening the real beauty and the differences in everyone’s experiences.”

We discuss the Eurocentric nature of much of the Australian art world—even when art from around the world is included and exhibited, it is, frustratingly, often in a way that is introductory and misses the depth and complex cultural context of the work. “A lot of my work is about pushing that Australia is not a white place, and that there are black and brown people of many different shades and that we belong here,” Eshrāghi says.

“I’m very aware and critical of how race is weaponised in this country. Australia is in Asia, it is in the Pacific, and yet Australian visual arts behave like we’re Atlantis, somewhere between the US and the UK in the North Atlantic. It’s a disembodied, de-territorialised outlook and it needs to shift, because this is not the future.”

So, what is the future? “I want to see far more incredible black and brown artists taking up space, but also for their work to be interpreted in a sophisticated way,” the artist says. “It’s so lazy to not look at the work for itself as work, and see it as identity art.”

Eshrāghi prefers the term ‘belonging’ when talking about what others might call identity: “who I belong to, who claims me and in a larger sense, which histories I am responsible for.” The many arms of their practice are all interlinked—as they say, “Everything that I’m interested in as an artist, I’m also interested in as a curator”—and is united by a desire to promote and enrich their communities. It’s something the artist sees as intrinsic to their cultural background, and distinct from the self-centred modes in which whiteness often operates.

“In Islander cultures it doesn’t really matter who you sleep with, or how you identify—it’s how much you contribute to the community that is important,” they say. “That’s really how I see my artistic work, my curatorial work—it has to be helping out in a way that I think is different to European ways of being, where the individual is king.”

As a curator, Eshrāghi is in the position where they can actively challenge and change some of these old ways of thinking: “It’s interesting to feel like you’re on the outside for a very long time, and then suddenly I’m working in two roles where I get to push some of these conversations a bit and expand people’s understanding of what Australia is and what it isn’t.”

Blue Assembly: Oceanic Thinking

Group exhibition

UQ Art Museum

19 February—25 June

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.