At 90, Janet Dawson has spent a life drawn to the light and energy of the natural and celestial worlds as she crosses boundaries of abstraction and figuration.

Her dressmaker mother, Olga, was the first to teach her to examine the everyday, from clouds to chooks to a cauliflower on their kitchen bench. “She could draw but recognised in me something she had not had; the power of pushing it further,” the artist recalls now.

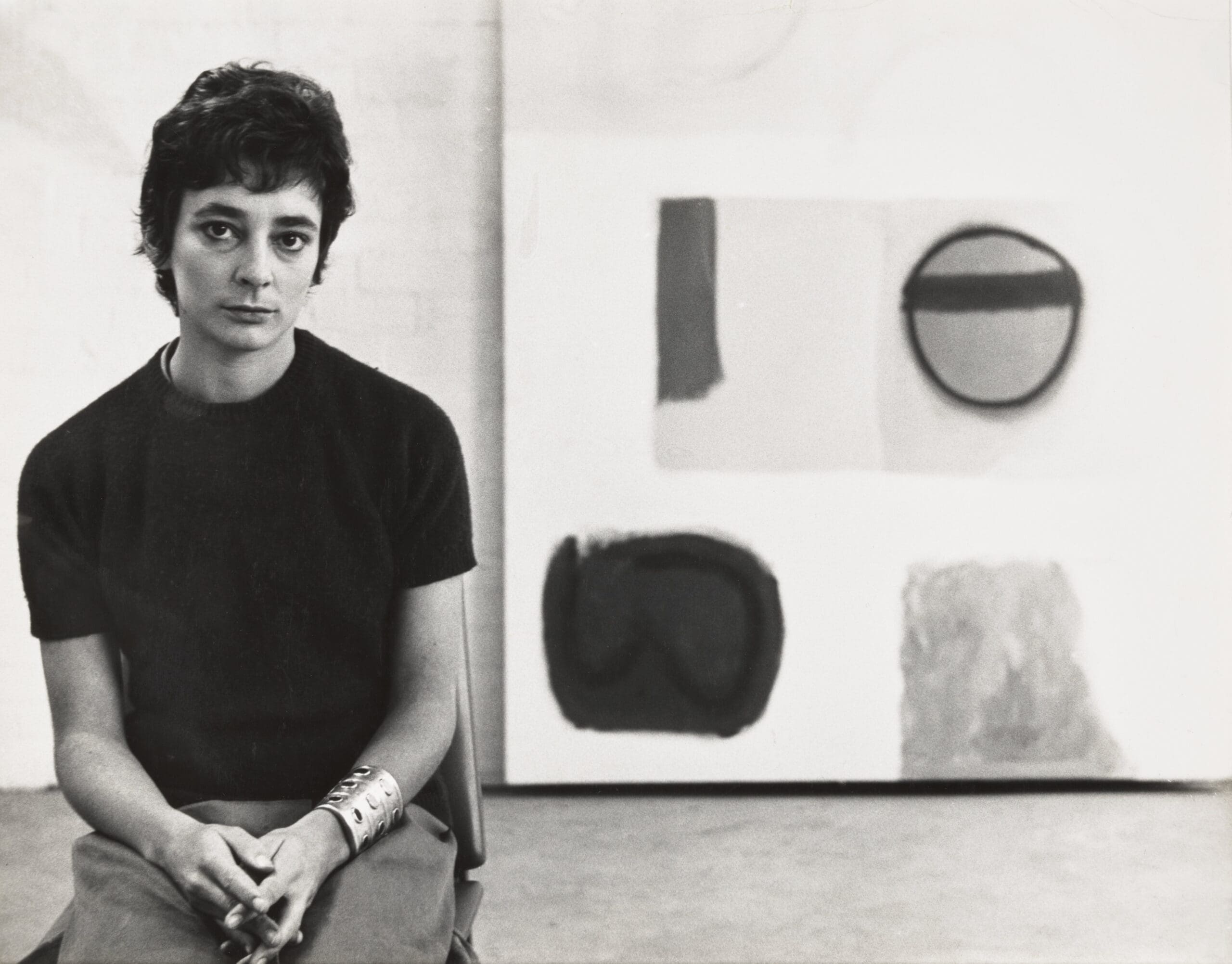

Dawson is in Sydney after two days of being driven from her home of recent years in southern Victoria. Seated in the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) members lounge, she is readying for the opening of her 80-work retrospective Far Away, So Close, her first by a state art museum.

The exhibition chronologically charts her career beginning with her studies in tonal realism at Melbourne’s National Gallery School, through her 1956 travelling scholarship to London’s Slade School of Fine Art and onto her employment at a Paris printing studio.

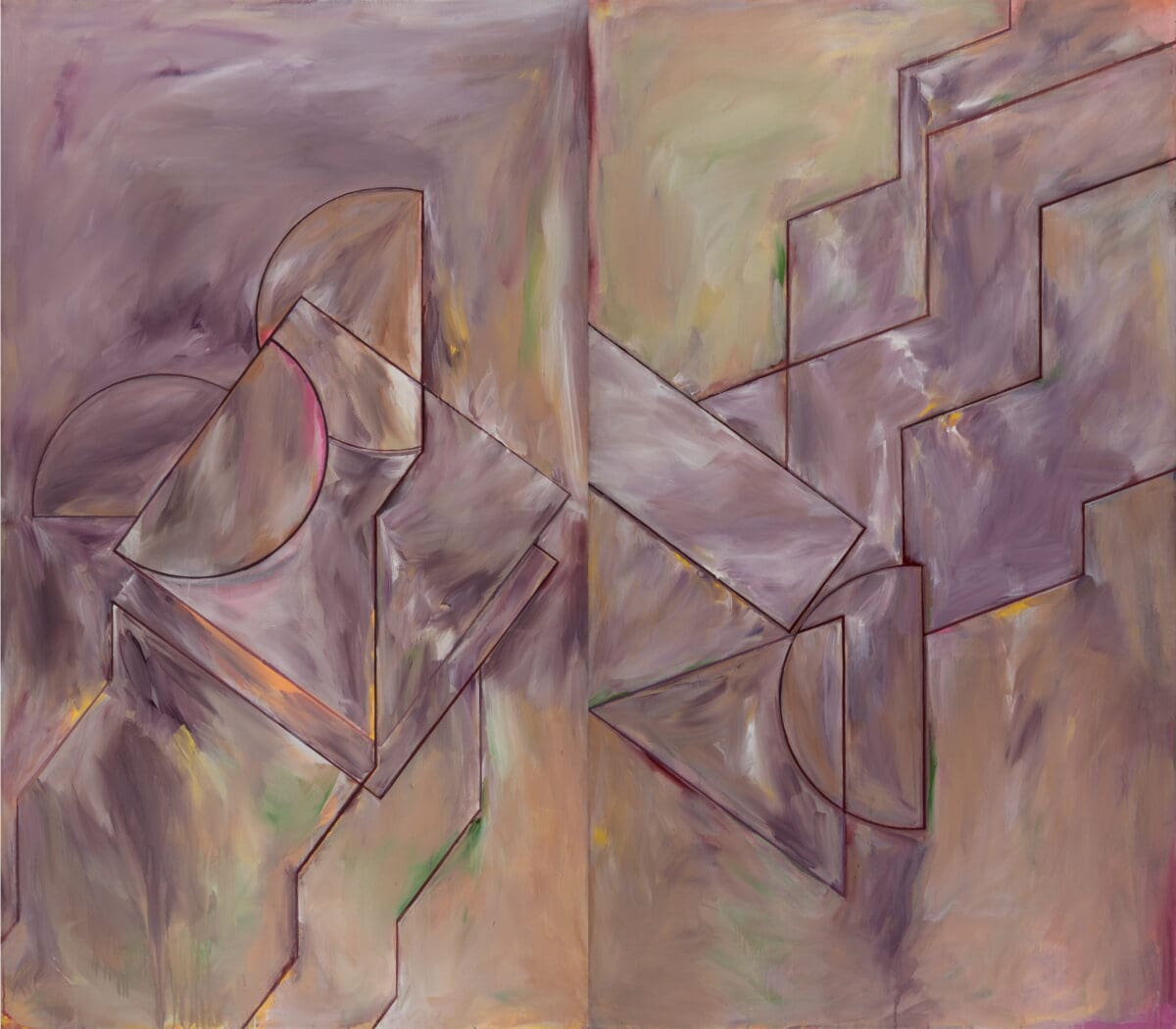

Returning to Melbourne in 1960, having embraced the European abstraction influence, Dawson’s take was more tonally modulated than the severe colour-field works displayed beside hers by the predominantly male artists at the seminal 1968 group exhibition The Field at the National Gallery of Victoria.

She shaded her edges, resisting the hard rules of abstraction. “I felt the purer [abstracted] ones were emotionally somehow dull,” she says now. “I always want a painting or drawing I do to have a little energy and a sense of self. Even dull, abstracted works need to have a reason in them to be what they are.”

Her 1970 polymer on canvas work Ripple 3 greets audiences in the exhibition’s second room: a luminous horizon meeting the kinetic green-blue currents of Sydney Harbour, painted two years after her move to this city.

She smiles now at the memory of the light here: “Riotously gorgeous,” she recalls.

Her lifestyle and career would soon converge as one: in 1968, Dawson had married the Yorkshire-born playwright Michael Boddy, and between 1969 and 1971, she worked as a production assistant at the Australian Museum, putting together cabinet displays and making scientific drawings of fossils and specimens for its publications.

This embrace of the natural world felt like a calling. “I feel a deep connection to the human world [as well], rattling on in here,” she says, pointing to her head, making clear her artistic expression became a means of overriding mind chatter. “So, I go to the natural world to relieve myself of the silly human world … I feel a complete connection to the natural world.”

In 1973, Dawson broke from what she once termed the “adulterated abstraction” she had become known for to paint a realist portrait of Boddy, seated and wearing a straw hat and flanked by gardening tools, all motifs for their organic, earthy future. Her first and only entry into the Archibald, she became the third woman to win the coveted portraiture prize.

Denise Mimmocchi, acting head of Australian art at the AGNSW, says she is one of many who believe a Dawson retrospective is well overdue: “Her story as an artist is this painter who increasingly immerses herself in the details of the natural world,” she says.

“Her work should be understood as important in the development of landscape painting in the 1970s, but her [physical] distance has seen her written out, to some degree, of the histories … her work became removed from the urban art world.”

By 1974, Dawson and Boddy had left the Sydney scene, moving close to the rural village of Binalong on the New South Wales Southern Tablelands. They established an organic fruit and vegetable farm at their property, Scribble Rock, by Balgalal Creek, writing and producing some 50 issues of a regular farming and kitchen bulletin detailing Boddy’s deeply researched organic methods and featuring Dawson’s drawings of produce.

“They were symbiotic, like the earth itself, those two,” says Storry Walton, a writer and television producer and long-time friend of the couple, who is seated beside Dawson now. “They lived as though they were creatures of the earth.”

Once quizzed by a journalist why the couple had left the city where artistic ambitions might be fulfilled, Boddy replied: “Our marriage is one long conversation. We moved to the bush so we could talk to each other without so many interruptions.”

Those four decades were fruitful for Dawson’s artistic output, however—vivid, unsentimental still lifes of dead animals such as a kookaburra, a rabbit, a tawny frogmouth are all on show in the retrospective, as well as many efforts to capture the subtleties of clouds and light. She produced rounded, telescopic oil paintings of the moon and pastels of Binalong’s landscapes by night.

Boddy would critique Dawson’s work “all the time”, she says now with a laugh, particularly the practical pictorial details.

“He’d come in and say, ‘What are you doing? That’s ridiculous! You haven’t noticed the edge of that thing. That wouldn’t be able to stand up’. I’d say, ‘I was busy over here … all right, I’m getting to it’.”

The couple would remain together at Binalong until Boddy’s death in 2014.

Despite a lifetime of the artist gleefully crossing boundaries, the retrospective draws parallels across time in Dawson’s use of structure, colour and light, such as between her 1964 painting The origin of the Milky Way in the first room and her late-career masterpiece Scribble Rock cauliflower, painted between 1993 and 1997, in the final room.

The comparison neatly ties together Dawson’s fascination with all forms of life, finding the cosmos in the quotidian of a cruciferous vegetable.

In 2016, Dawson left Binalong to live with family at Ocean Grove on Victoria’s Bellarine Peninsula, where her niece Penny is her carer.

But, she says, “Binalong sits in my head as where I actually live”. She still draws, but if the image does not make it to paper, she draws in her mind. She leans over now and points to this writer’s arm, describing how she might paint it, muting the line between the purple pullover and forearm flesh.

“It’s just that awareness of being alive every minute and noticing the colours together,” she says.

Janet Dawson: Far Away, So Close

Art Gallery of New South Wales

(Sydney/Eora NSW)

Until 18 January 2026