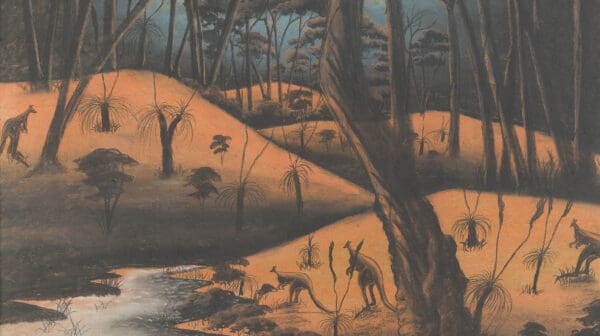

Renee So’s playful and irreverent work engages with art history, museum collections and societal structures in an idiosyncratic way. Born in Hong Kong, raised in Melbourne and now based in London, the artist works across ceramic, print and textile forms, interrogating gender, race and social mores through her own interpretations of recurring figures such as Bellarmine jugs. Provenance is her first survey exhibition in Australia, spanning over a decade of interdisciplinary artistic practice.

In our interview she talks about her multidisciplinary practice, art history and museum collections—and how her work looks at “being a female, being Asian, being a mum, being an artist and living in the world”.

“The work in the exhibition spans about 14 years. I can look back on it and I can see that it mirrors my biography a little bit—it’s in parallel to my personal development.”

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen: How have your interests and practice developed or evolved over your career?

Renee So: The work in the exhibition spans about 14 years. I can look back on it and I can see that it mirrors my biography a little bit—it’s in parallel to my personal development. It starts at the time when I moved to England, so I can see that observation of going to a new country and when I first encountered artifacts as I was traveling and going to major public museums and seeing their work for the first time, and getting to know British culture a bit more. I think that’s why there’s that interest in social drinking, because when I first moved to London, I was going to a lot of art openings, so that would be a real thing that brought people together.

I became more interested in clay as an art material, so I also started looking at museum collections and following the history of clay through artifacts of different cultures. Then I had a baby when I was around 40, and then that shifted my interest from looking at representations of the male body to the female body. That’s when my interest in the Venus figures and the fertility symbols began.

GAN: You have recurring visual motifs in your work, many of which are based on traditional forms. How do you engage with art history?

SO: I think we just remember stuff. I saw the Babylon gate the first time I went to Berlin, those glazed bricks used as a building facade—that didn’t start to appear in my work for another eight years. You just remember things and it’s somehow embedded in your brain so that when you start making work, you think it’s your own idea, but it’s actually something that you’ve seen, and it’s not until you have an exhibition like this, and you look at things in depth that you can see where all those influences come from. Everything that you thought of has already been brought up by someone else before, and if you look deeply enough, you can pinpoint where you saw it.

“There’s lots of talk about repatriation, but I don’t feel like anyone’s really talking about Chinese loot—no one is demanding for it to be returned.”

GAN: What are the points you want to make about museum collecting practices?

SO: Everyone has different responses when they go to a museum and see stuff. They present themselves as global and everyone’s supposed to get fed the same label and the same information, but everyone responds differently, depending on your identity. For some people, it’s really painful. For some people it’s offensive. Some people are just full of admiration for the object. It’s a personal experience, and I guess I’m just presenting mine.

There’s lots of talk about repatriation, but I don’t feel like anyone’s really talking about Chinese loot—no one is demanding for it to be returned. Things get sold at Sotheby’s all the time and it just doesn’t seem to have the same focus that the Elgin Marbles have in terms of public consciousness.

GAN: Is that something you want to change with your work?

SO: I don’t know what I can do personally, but I guess highlighting it could get people thinking about it. It’s going to happen with public pressure, I think. The museum directors or the people in charge don’t really want anything to change—they like it as it is, being able to sell stuff and not worry about where it came from, and having beautiful things in their museums.

GAN: You play with gender in your work through the bodies of your characters. How is this informed?

SO: With the men, I haven’t really addressed the male body—I look at the constructs, the adornment that they use to project something, like the beard, which is a choice. With the females, I have addressed the physical body, but I’ve kind of looked at the internal body as well by the form of the clitoris. I also try not to make them look too human because I don’t think of them as people—they’re an idea of a human, of a body.

GAN: What role does humour play in your work?

SO: If you’re serious all the time, it’s harder to get people to engage if it’s too heavy, so I guess it’s a choice to make the work a bit more approachable or appealing, so people don’t get turned off or turn away from it. It’s just me making it accessible so everyone can engage with it at whatever level they want.

“I think it’s instinctive and personal—it’s really just to do with just being a female, being Asian, being a mum, being an artist and living in the world.”

GAN: You work across many different mediums. How do the arms of your practice intersect and how do you choose the form for each work?

SO: I see them working together really well, I guess because they’re tactile materials—they’re considered craft, so they’re kind of on the margins of contemporary art anyway. It’s materials you don’t see a lot of in a contemporary art context, but it’s definitely changing—when I was doing the knitting 10 years ago, I wasn’t seeing that much textile around. It’s different now.

I think it’s instinctive and personal—it’s really just to do with just being a female, being Asian, being a mum, being an artist and living in the world. I get a lot of ideas from the news and current affairs.

GAN: How does your feminist worldview impact your work?

SO: It’s not something that I set out to do—it’s just part of who I am. There’s a lot of imbalance in the world. It’s not a political thing, it’s just observations and things you see and how you live in the world. I think it just comes out.

Renne So: Provenance

UNSW GalleriesOn now—19 November