Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

In 2005, John Olsen finally won the Archibald Prize for his muted brown oil work Self portrait Janus faced. His ghostly twin visage appeared to be simultaneously looking back at his disaffected relationship with Australia’s most hyped art honour, and forward at posterity in a nation that had once struggled with narrow notions of portraiture.

Self portrait Janus faced wasn’t initially painted for the Archibald, however, because Olsen was still smarting from the time his painting Dónde Voy? Self-portrait in moments of doubt failed to take the Archibald some 16 years earlier—Dónde Voy? being roughly Spanish for “Where am I going?” He’d been led to believe his portrait may be the winner.

Olsen was only persuaded to enter his Janus work in 2005 after campaigning by former National Gallery director Betty Churcher: “I said to John, this is a serious work, the Archibald needs it.”

When Olsen died on 11 April at the age of 95, obituaries rightfully noted he was celebrated and acclaimed, even a “daring art titan with a stroke of genius”, but curatorial acceptance of Olsen’s innovations in landscape and portraiture took time.

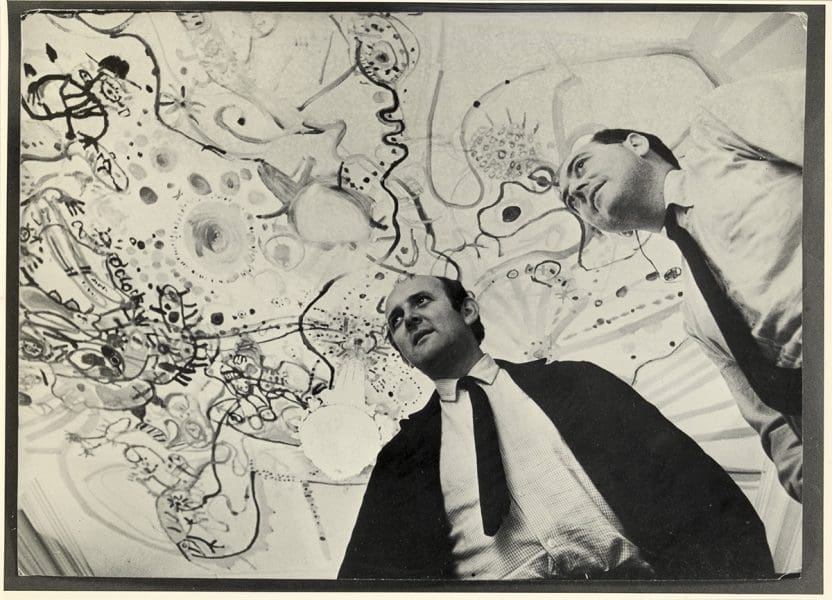

Painting in oils and watercolours, his abstract style departed dramatically from the realism that dominated Australian art into the second half of the 20th century. He also worked in ceramics, tapestry, and printmaking.

At 41, Olsen was awarded the 1969 Wynne Prize for landscape painting for The Chasing Bird Landscape, an honour he won again in 1985, followed by the Sulman Prize for best subject or genre painting or mural project in 1989, awarded for Don Quixote enters the inn.

Steve Alderton, the National Art School director, who curated the artist’s final survey, John Olsen: Goya’s Dog, in 2021, recalled Olsen “spoke of the Spanish influence and of interpreting the peaks and troughs of the human condition”.

Australia has now “lost one of our truly remarkable and emblematic artists. John redefined the way we see ourselves, our landscapes, our country and our shared identity,” Alderton said. “He was a poet of the Australian landscape, a storyteller of our country and a lyricist of humanity.”

And as Pip Wallis, senior curator, Monash University Museum of Art, remembers, “John Olsen lived a life committed to the practice of art making and to the explorations, adventures, joys and complexities of being an artist… Olsen’s contribution to our collective cultural life is hugely significant.”

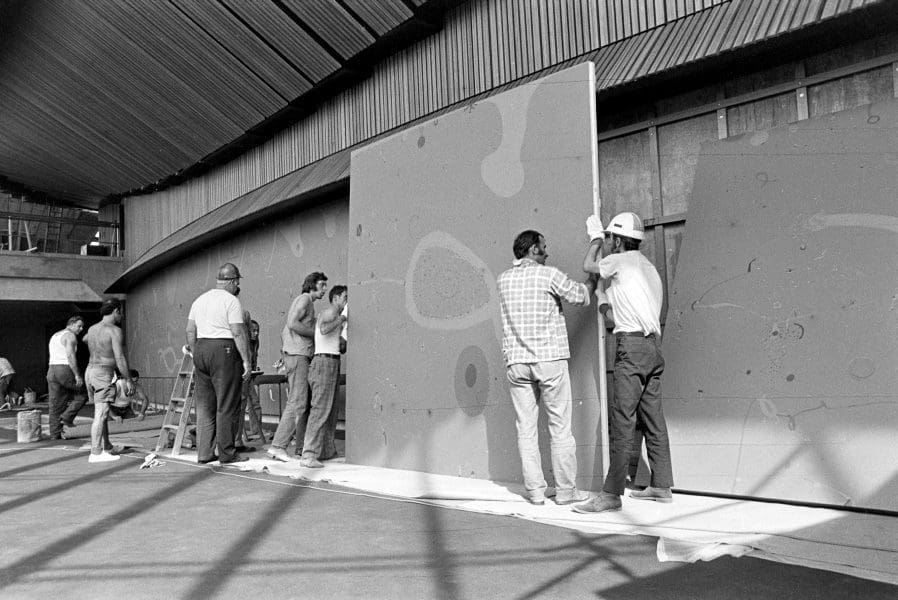

In honour of this, in May one of Olsen’s most iconic artworks, My Salute to Five Bells, will light up the Sydney Opera House.

Born in Newcastle in 1928, Olsen was the first child of clothes buyer Henry Olsen and tailor Esma (nee McCubbin). He described making art, which he began at age four, as an act of compulsion.

The family moved to Bondi shortly after their second child, Pamela, was born in 1934. Olsen studied at the Julian Ashton Art School, Datillo Rubbo Art School and East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School).

In 1952, as a 24-year-old art student, he led a protest march around the Art Gallery of New South Wales against the fervently realist portrait painter William Dargie, who that year won a seventh Archibald prize and would go on to win the honour an eighth time.

In 1955 he took part in the exhibition Contemporary Australian Paintings: Pacific loan exhibition and in 1956 he showed in an exhibition of abstract works Direct 1 alongside Robert Klippel and John Passmore.

Living in Europe from 1957 to 1960, primarily in Spain, he was influenced by artists Antoni Tàpies and Jean Dubuffet and became interested in Eastern philosophy and poetry, painting the triptych oil work Spanish encounter upon his return to Australia.

Olsen’s local sources of inspiration included Lake Eyre (Kati Thanda as the Arabana people call it) in South Australia, which he felt drawn to as a spiritual place, as well as the spark and pulse of Sydney Harbour, leading him to his 1963 painting Five Bells, inspired by the Kenneth Slessor poem, and the 1973 mural Salute to Five Bells, which hangs in the Sydney Opera House.

But Australia’s arts establishment continued to resist the charms of abstraction in portraiture. In 1963, Olsen angrily denounced the awarding of the Archibald to artist Jack Carington Smith, claiming: “They are such stodgy incompetent judges that most major portrait painters will no longer enter the prize.”

By the 1970s, the tide turned: Olsen was a gallery trustee himself for four years, and part of the judging panel that awarded the Archibald in 1976 to Brett Whiteley for the oil, collage and hair canvas Self portrait in the studio.

Olsen had three children: with his first wife, Mary Flower, a daughter, Jane, a teacher and artist who died in 2009; and with his second wife, Valerie Strong, a son, Timothy, who became an art dealer, and another daughter, Louise, who became an artist. Olsen wed twice more, to Noela Hjorth and then Katharine Howard, who died in 2016.

That year, at almost the age of 89, Olsen told the ABC he still painted every day, “as a habit, because it’s me. I mean, what [else] would I do?”.

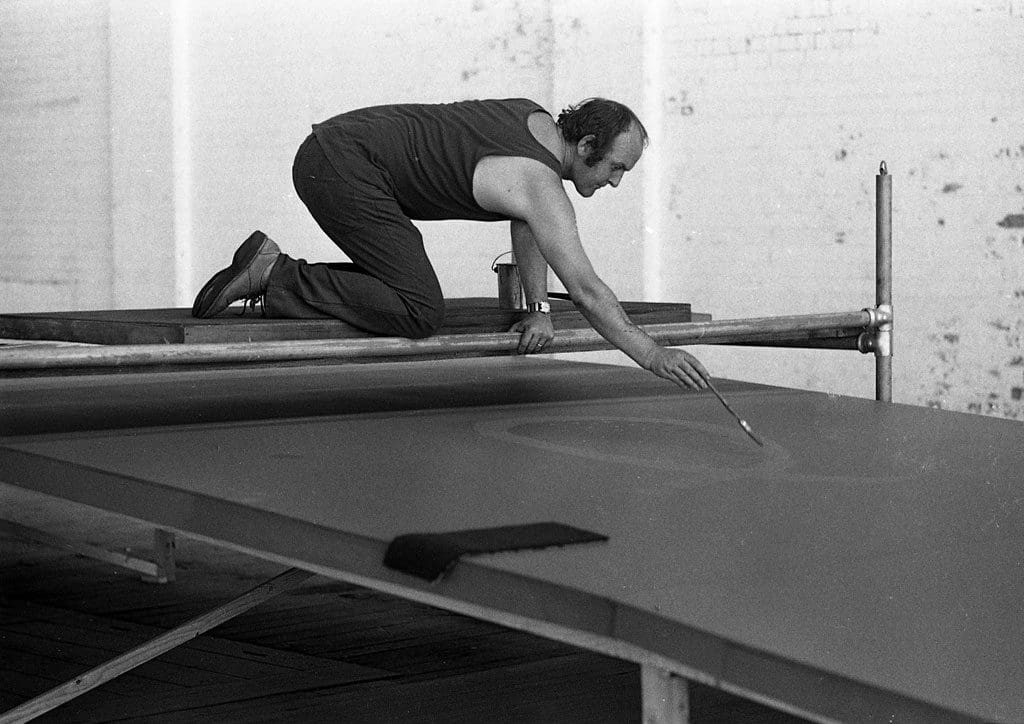

He had no problems with the physicality of working on his large canvases. “When I’m painting, I don’t have any age,” he said genially. “The wonderful thing about a creative life is this: you never know everything. You’re always searching.”

Tim and Louise Olsen said their father was still painting until last Saturday in his Southern Highlands studio, 120 kilometres southwest of Sydney.

And his opinions still burned bright, with Olsen criticising the new guard, specifically Mitch Cairns’s Archibald prize-winning portrait of Cairns’s artist partner Agatha Gothe-Snape in 2017. “I think it’s the worst decision I’ve ever seen,” grumbled Olsen. “It’s entirely surface, the drawing is just not there, and the structure, which is a summation of what makes a thing good, isn’t there.”

Perhaps at the heart of Olsen’s radical abstraction was a belief in essentialism, that talent is innate. “Artists are born, not made,” he said.