Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888, oil on canvas. Tate collection, © Tate.

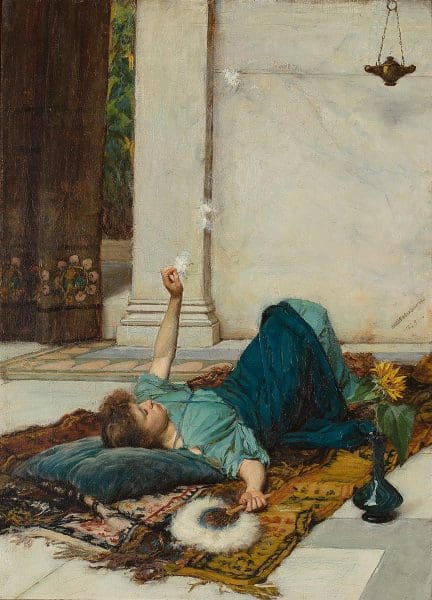

John W. Waterhouse, Dolce far niente, 1879, oil on canvas. Private collection, Melbourne.

William Morris, La belle Iseult, 1858, oil on canvas. Bequeathed by Miss May Morris 1939, Tate N04999. © Tate, London 2018.

Whether seen in their native environment at the Tate Britain or on one of their rare tours abroad, the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood are attended not only by the lore of their makers’ consuming passions, but also their weighty cultural aura. John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851-1852) is staggeringly well known. A besotted public buys this postcard more than any other at the Tate Britain. Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott (1888) breathed brightness into the characters of Arthurian legend and informs the imagery of medieval romance even today. Love and Desire at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) will bring 100 Pre-Raphaelite paintings, drawings and decorative objects to Canberra from the seminal holdings of the Tate and collections across Australia and New Zealand.

Founded in London in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, the self-titled Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was fast burning and close-knit. After five intense years, their ranks enveloped a succession of artists including William Morris, Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones and John William Waterhouse. They drew on literature and theory spanning Keats, Ruskin, Tennyson, Shakespeare and the Bible, and used newly developed pigments like cobalt blue and the absinthe-green of chromium oxide to paint luminous and beguilingly detailed works. Unorthodox and earnest, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood positioned painting and the pursuit of integrity as central tenets of their lives.

“We must remember that they’re one of the first avant-garde movements,” says NGA curator of international painting Lucina Ward. “The Pre-Raphaelites parallel and pre-date the French impressionists in this sense.” That their pictures of striking, rounded women and sumptuous settings are so well loved can somewhat mask their initial disruptiveness. These paintings were repugnant to the establishment, who believed that realism was antithetical to good composition and skilful manipulation of form. In Byron-esque riposte, the Brotherhood flung itself toward a form of realism that honoured nature, sought the profound and gave itself over to beauty and abundance.

The Pre-Raphaelites fiercely aligned themselves with English critic John Ruskin’s “trumpet-call to painters to go humbly to Nature, rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, scorning nothing.” Working on Ophelia, Millais spent five months “studying seemingly every petal en plein air,” explains Ward. Hunt painted his working-class models as is, big noses and dirty fingernails. “We see in his paintings the inhabitants of 19th-century London. It shocked people,” says Ward. In Household Words, Dickens called Millais’ depiction of Mary a “monster in the lowest gin-shop,” and his Christ “hideous” and “blubbering.” In fact, the Brotherhood was in the business of proclaiming the power of Christian stories by that very worldliness. They travelled to the Middle East to study the landscapes of Jesus’s life and painted holy figures with human foibles.

Love and Desire examines the Pre-Raphaelite story in chapters dedicated to modern life, faith, nature, love, literature, and portraiture. The exhibition concludes with “a room of femme fatales”: Waterhouse’s cursed Lady of Shalott (1888) is flanked by his bewitching yet murderous Circe Invidiosa, wielding a basin of incriminatingly green poison (1892) and Rossetti’s Venus Astarte (1876-1877), in which “model Jane Morris steps forward, strong and determined in sheer emerald robes,” describes Ward.

Love and Desire arriving in Canberra reminds us of the indefatigable capacity of Pre-Raphaelite art to pervade outside traditions. Ophelia’s limp body wreathed in wildflowers is echoed throughout Australian lyricism, in Paul Kelly’s Everything’s Turning to White (1992), about a woman’s floating body discovered by fisherman; the soft-focus riverside murder in Kylie Minogue and Nick Cave’s 1995 duet Where The Wild Roses Grow; the body among the flowers in Lantana (2001); even a tuxedoed Noah Taylor submerged by love in He Died with a Falafel in his Hand (2001). “The influence of Pre-Raphaelite subjects on popular culture, particularly music, are really important,” says Ward. A recital by Sarah Blasko and a night of song and feasting are two events in a wider program, which Ward says characterise the on-going uptake of Pre-Raphaelite tradition by contemporary culture.

A room centred on “second-wave” Pre-Raphaelite William Morris, measures the reverberation of Brotherhood principles through domestic design. The layered patterns and fabrics in Morris’s only completed painting La Belle Iseult (1858) “prefigure the next phase of the aesthetic movement, where artists designed entire living spaces, down to matching clothes for the lady of the house.” Though such bespoke decoration is prohibitively expensive, Ward marks the importance of holding that ideal against our contemporary backdrop of cheap, seasonal decoration. “His work reveals how extraordinary objects can feed quality of life,” she explains. “Low-quality décor and its part in landfill would have been abhorrent to Morris. Maybe what we need is one exquisitely crafted handmade object in our lives, instead of multiple mass-produced objects.”

Love & Desire: Pre-Raphaelite Masterpieces from the Tate

National Gallery of Australia

14 December – 28 April