Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

This article is written by Darren Jorgensen, The University of Western Australia and Joseph Yugi Williams, Indigenous Knowledge

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

On June 5 1960, the Darwin paper The Sunday Mirror reported:

A tribal painter, said to be more famous than the late Albert Namatjira, has just died at Warrabri welfare settlement, near Tennant Creek. He was Nat Warano, of whose skill few white men had heard.

Locally, Warano is remembered as Tracker Nat.

Born in the 1880s, Nat worked as a drover during the 1930s, before becoming a police tracker. He was also a leader and diplomat of the Warumungu people during a tumultuous period of their history.

During the 1940s and 1950s Nat was a prolific carver of coolamons, spearthrowers, shields and water carriers, painting them with men dancing in ceremonial dress and body paint, as well as men hunting with boomerangs and spears.

This style of painting scenes of Warumungu life onto carvings was unique. The details of animals, vegetation and weapons show both a personal style and a deep knowledge of what he was painting.

As well as selling painted carvings, he gifted artefacts and drawings to missionaries, teachers and government officials so as to draw them into the Warumungu system of a ngijinkirri, a mutual gifting that implicates the giver and receiver into a relationship of obligation.

Yawalya Elder Donald “Crook Hat” Thompson explains:

Ngijinkirri is like paying back, might be tucker, like a kangaroo or an object. Everyone, all tribe from all around practise this. Like when a school teacher gives you knowledge, you owe them. Maybe pay you with a full kangaroo, pay you with an emu, but no money.

During the 1950s, Nat made hundreds of carvings. Today, many of these are likely to be lying unidentified in people’s homes and in museum basements.

A surviving photograph of Nat shows him at the official opening of the Warrabri settlement, now Ali Curung, in 1958.

He stands next to the federal minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, who holds a shield with Nat’s distinctive motifs painted upon it. An unidentified man holds a second shield painted in Western Desert style, with roundels and dots, probably made by Engineer Jack, standing to his left.

Since the 1890s, the Warumungu had been shuffled from one settlement to another, from ration station to reserve to mission. The local Aboriginal population boomed after the Coniston Massacre of 1928 sent people in search of a safe place to live, and the Warumungu people opened up their country to Warlpiri, Kaytetye and other refugees from frontier violence.

Jack and Nat, the senior men for the Warumungu and Warlpiri respectively, worked together to keep the peace and on ceremonial matters, and it was these men who were tasked with talking to the government about moving the community to Warrabri.

Phillip Creek was running out of water, which was the reason for the move, but Nat was also concerned that Phillip Creek was too close to sensitive cultural sites.

The gifting of the shield to Hasluck was Nat’s way of extending his authority into white society.

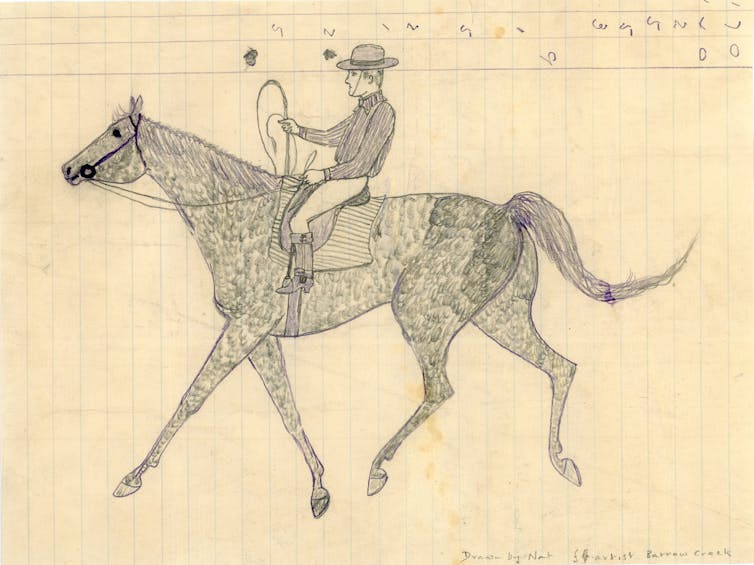

Nat also made drawings, the earliest of which can be dated to 1929. Some are of his time working on cattle stations, with detailed depictions of long horned cattle.

Like so many Aboriginal carvers of this era, Nat’s name was forgotten after his work was collected by people making trips to remote Australia.

This is a tragedy not only for Nat and his family but the greater story of Australia, in which Aboriginal elders played significant roles negotiating on behalf of their communities, using art to forge a middle ground with settler Australia.

We rediscovered Nat’s work after discovering a newspaper essay about his drawings, and seeing a pair of his shields come up for auction. Since then we have been looking for them, and have found several carvings in public and private collections.

One of the authors of this paper, Joseph Yugi Williams, is Nat’s grandson and a contemporary artist. He has been re-enacting Nat’s work with a series of shields inspired by his artefacts.

We hope to find more Tracker Nat works in the future and plan to have an exhibition in the next couple of years that showcases his originality as an artist and his significance for Warumungu people.

Darren Jorgensen, Senior lecturer in art history, The University of Western Australia and Joseph Yugi Williams, Artist and Men’s Art Facilitator, Nyinkka Nyunyu, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.