Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

Rebecca Belmore, Fountain, 2005 single-channel video with sound projected onto falling water, 2m25s 274 x 488 cm (overall dimension variable) Collection: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Image courtesy the artist.

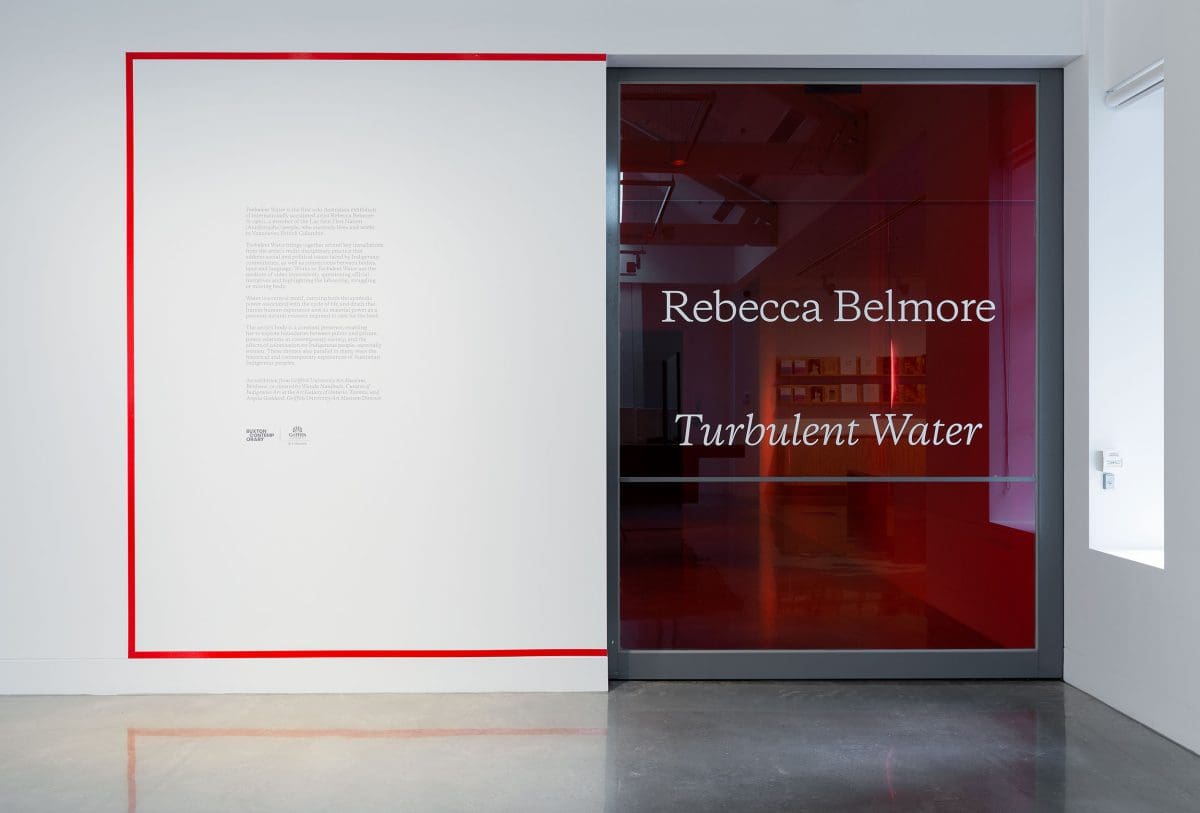

Rebecca Belmore, Turbulent Water, Installation view, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne 2021–22. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Christian Capurro.

Fountain (detail) 2005, Installation view: Rebecca Belmore Turbulent Water, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne 2021–22. Collection: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Courtesy the artist. Photograph: Christian Capurro.

The Named and the Unnamed 2002, Installation view: Rebecca Belmore Turbulent Water, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne 2021–22. Collection: Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Courtesy the artist. Photography: Christian Capurro.

Language is a source of power, a way to describe the world you want to live in. But for the renowned artist Rebecca Belmore, it can also be a means by which to silence, destroy and erase. Belmore is an Anishinaabe woman from the Lac Seul First Nation, part of north-western Ontario in Canada. Growing up, she spent summers on the land with her maternal grandmother, who refused to speak English. It was an act of resistance that stayed with her all her life.

“My grandmother spoke Anishinaabemowin,” she says. “Even as a child, that was a very inspirational moment about my thinking about what happened here. When you grow up in Canada, it’s all about singing ‘O Canada’ and looking at the Queen. When I was 10, 12, I realised that there was something not true about who we were.”

When Belmore’s thoughts arrive, they seem to animate her body before pouring out as words.

“In ’87, when the Royal Family were coming to the city of Thunder Bay, Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson were put in a birchbark canoe,” she says. “I made this gown and had braids that went straight up in the air to signify my anger.” Her cadence turns poetic. “The absurdity of the monarchy. The rape of the land and the destruction of the culture. The romanticism and the reality.”

Belmore performed that work, Rising to the Occasion, the year she quit art school in 1986. “I was only there for two years and ran away,” she laughs. “Whether I had the wherewithal to make contemporary art was being questioned. I was young, and I intended to be an in-your-face artist.”

She started making photographs. First: a 1995 series called Five Sisters. She decoupaged portraits of herself on pieces of wood, skewering the wooden ‘Indian’ heads, a fixture of Canada’s highways, that render Indigenous people passive objects in the landscape. Then, in 2002, came Vigil. “I had just come back from a residency in Trinidad, which has major violence against women and the mass murderer Robert Pickton had been arrested,” she tells me. Pickton, she adds, targeted vulnerable women from Vancouver’s disenfranchised Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, many of whom were Indigenous.

In response, Belmore shouts the names of each woman. She bites the head off a rose, spitting the petals on the pavement. Then, she puts on a red dress. She nails it to a telephone pole. She wrenches it off in bitter struggle. The performance, documented on video as The Named and the Unnamed, is electrifying, a call for the viewer to witness bodies that had been neglected, forgotten. Struck out of the national conversation. But like Untitled—a 2003 series in which her sister, Florene, appears as inverted, bound in a cocoon of fabric—the work also delivers moments of astounding physical grace.

“I think as Indigenous people, we’ve suffered so many humiliations and atrocities, but we still have humour, we still have a sense of beauty,” says Belmore, whose retrospective, Facing the Monumental, showed at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2018. “I don’t like the word ‘survivalist’. But it’s more like we’ve always endured.”

This tension propels Turbulent Water, Belmore’s first Australian solo exhibition, which premiered in March 2021 at Griffith University Art Museum in Brisbane. Now showing at Buxton Contemporary in Melbourne, Belmore will present The Named and the Unnamed alongside works like Fountain. This latter piece, a performance-based video installation, was first shown at the Venice Biennale in 2005, where Belmore became the first Indigenous woman to represent Canada at the event. In the work, the artist gathers icy water from Iona Beach, a polluted industrial site in Vancouver. Then, she hurls the contents of the bucket at the camera. The liquid turns into blood.

“In this community of Canada, the water is contaminated by industry, by resource extraction,” she says. “How many human beings on this planet have potable water? I was trying to speak about how water was going to become a war. We are already saying how water is [being] destroyed. We know it is precious. Why do we deny it?”

For Belmore, it matters who gets to speak and who doesn’t. In 2013’s Apparition, the artist kneels on her haunches, her mouth sealed with duct tape. This year, Belmore reminds me, the Canadian authorities discovered the unmarked graves of over 1300 Indigenous children, part of the residential school system that aimed to destroy their language, stories and culture. A while back, Belmore says, she watched Rabbit-Proof Fence, a film that tells the story of three girls from the Stolen Generations. She hopes to explore the parallels between the two colonies, on opposite sides of the world, in Turbulent Water. And this extends to language: unlike her grandmother, she doesn’t speak Anishinaabemowin. “I know that I’m [part] of the lineage of this system and what it did to us,” explains Belmore. “I’ve absorbed all this history and I can speak through the use of my body.”

Bodies can have power that is more than language. They can witness the tides of history. “I’m still trying to create something that is relevant that gives me some kind of pleasure as the maker,” she says. “Time keeps circling, keeps going forward. I think maybe now I’m more cynical. And I’m more worried than I ever was.”

Turbulent Water

Rebecca Belmore

Buxton Contemporary

10 December 2021—May 2022

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.