What can artists do for business? The question has been smouldering at the edges of my attention for some time.

On the first of March, I wrapped up the pilot run of the Feral MBA in Hobart. The Feral MBA is a radically different training course in business for artists, one that plays with the notion that artists might get hands-on with business as a site for wild experiments and meaningful work.

In these seismic times, the idea of business as a staging ground might seem counterintuitive. On the one hand, the arts are considered subject to an incoming tide of business vocabulary and values, encapsulated in the bonanza of the ‘Creative Industries’, which elevates creativity as a driver of productivity and economic growth. On the other hand, the capacity of ‘business as usual’ to maintain a habitable planet has unarguably failed.

While the business world has traditionally flirted with the arts as a means to signal its commitment to culture—or at least decorate its foyers—these attentions are often not reciprocated. Some artists I know do face up boldly to the entrepreneurial ethos of the marketplace. But most place themselves firmly outside of an engagement or facility with business, its processes and paraphernalia.

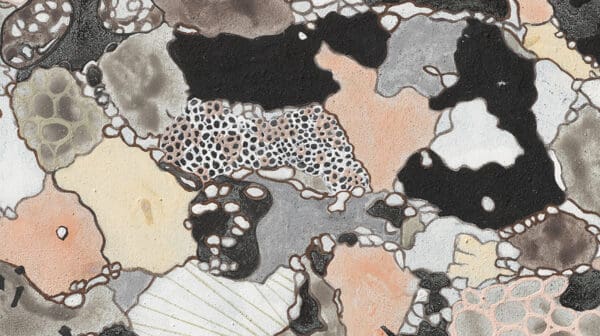

However, the fractures and frictions between art and business might also indicate an uncommon potential for artists to contribute to this space. Artists are skilled at playing with form, but rarely extend that superpower to the fabric of their own livelihoods. What if instead of avoiding the topic or railing against it, we turned our attention to business as a medium and material?

My fascination here is not with the many artists taking business as the subject of their artworks—art about business. Nor is it in producing the foyer decorations for the cooperatives and social enterprises— art for business. The opportunity I’m glimpsing at this deadly juncture for human and planetary survival is art’s signature capacity to render the world as it could be, working in and with business for real.

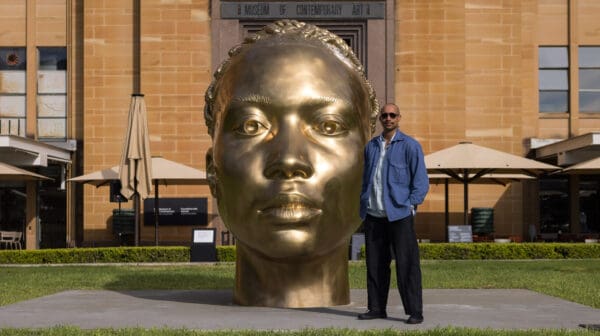

For inspiration, we can turn to a constellation of precedents and peers. In the UK, the 1960s collective Artist Placement Group (APG) pioneered artist placements in industry and public institutions, landing artists inside government departments, universities, British Steel and Esso oil tankers. The placements were established with an ‘open brief’— the then (and still) revolutionary concept of engaging artists in new contexts with no specified outputs or outcomes, as a public value in itself.

There are other examples from my contemporaries. Minipogon, a collective of artists, scientists and activists, have started an experimental plastics recycling unit in Belgrade, Serbia, dedicated to processing and transforming the residues of the capitalist system into useful and beautiful objects, and radically re-conceived working relationships. In East London, England, Company Drinks—an art project in the form of a drinks enterprise—run an annual production cycle of growing, picking, processing, branding, bottling, trading and reinvesting; here the commercial supports the communal and the cultural. And then there is my own work with Feral Trade, a sole trader grocery business dealing coffee, olive oil, bamboo shoots and other vital provisions internationally since 2003. Goods travel in the spare baggage space of friends, colleagues and passing acquaintances: an underground freight network forging convivial and resurgent supply chains.

Such direct interactions between art and business function, as art critic Stephen Wright points out, at a 1:1 scale. Not confined to the timeline of the project, commission, exhibition or funding round, they are not speculations or prototypes. Instead, the artists and artworks operate at the same scale as the issues they are dealing with.

Other endeavours on my radar don’t fit the category of art at all, and don’t need to. In Europe, the New Dawn Traders are brokering radical collaborations amongst food producers, ships’ captains and port allies to reinvent the art of hauling cargo on wind-propelled ships. In South Central Los Angeles, Community Services Unlimited is transforming the justice- driven political heritage of the Black Panthers into a neighbourhood produce market, kitchen and farm.

These examples all point to some of the qualities that business, as a medium, has going for it. It is malleable, collaborative and designed for longevity. It’s widely understood and accessible. It can also act as a Trojan horse, able to enter into otherwise inclement environments. Now, under the drastic intervention of COVID-19, this thinking is particularly salient. What the pandemic has unfurled is a world-scale experiment in which the short-term plans and future imaginings of business have been shaken to the core. While the pandemic’s impact on the arts has been drastic, it also offers a potential opening—to take up Arundhati Roy’s invocation of the rupture as a portal into possible liveable worlds, but with business as the vehicle of investigation.

Business is something that is not quite ‘us’, yet also not quite ‘other’. We can consider it as an avatar or exoskeleton in which we might navigate and engage with this hostile, yet contestable, terrain we hazily describe as ‘the economy’. This is also a highly practical endeavour, with the potential to cultivate diverse forms of livelihood, trade, encounter and sustenance—well beyond the depleted monocultures of arts funding.

What’s holding us back? Acumen, tools and a sense of material agency to engage with this space. This is where a fundamentally different kind of training course in business is called for. In the aforementioned Feral MBA pilot in Hobart, artists and others were practising deep listening to understand each others’ livelihoods. They were cultivating uncommon business capacities of inconsistency, contradiction and counter-efficiency. They were tackling business as something to experiment with, in the same way that artists would normally experiment with materials.

The challenge is not to revive a failing economy but to imagine it anew—with business as a vital site to put our thinking into action.