Making Space at the Table

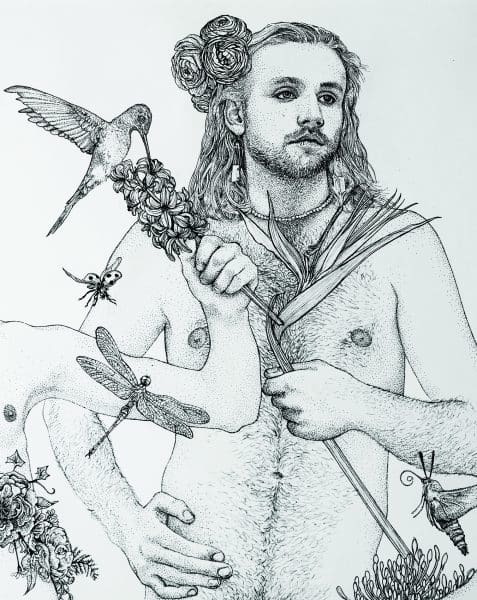

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In Perth-based artist Colin Smith’s installation Bloodletting, a Catholic-style confessional booth is fitted with medical furniture and a green curtain. There is also a water cooler and a palm tree to signify a doctor’s waiting room. A pair of clay leeches and a series of red monochromatic paintings reference the act of blood extraction, according to Smith, who is trans and uses the pronouns he and him.

The work reflects in part the “bureaucracy of medical transition”, he says, but the aim here is a more intimate quest for meaning. “I was looking into the alignment of the soul and the body, conflating the two into a ritual space that explores those ideas.”

Bloodletting is part of the group exhibition Here&Now20: Perfectly Queer at the Lawrence Wilson Gallery at the University of Western Australia (UWA), for which nine artists draw on queer histories and personal experiences.

Smith grew up in a Catholic family. His uncle was a priest and he went to Mass, but Smith says he wasn’t exposed to any anti-queer teachings. His later experience with medical institutions was “overall, definitely positive, but it’s emotionally taxing in the bureaucratic and legal aspects of it, as well as the scientific monitoring, which I’m not fluent in,” he explains.

“I felt I didn’t have control over certain aspects of my situation. My doctor will know more about my identity than I do in certain situations, because she has a scientific knowledge I don’t have.

“A lot of my transition was emotional and feelings- based that I just kept acting on.”

Exhibition curator Brent Harrison says that in bringing Here&Now20: Perfectly Queer together, he’s been grappling with what it means to call yourself a “queer artist”.

“‘Queer’ is partly about being able to not be defined, so there’s a slipperiness,” he says. “All of the artists in the show take such a different approach, and none of the works are similar in their methodology or how they motivate and use queerness within their work.”

While celebrating an expansive contemporary understanding of queer identities, with a number of exhibiting artists identifying as non-binary, Here&Now 20: Perfectly Queer affords its audience the opportunity to draw parallels with 20th century Australian artists who also ill-fit binary identifications— and whose sexualities were problematised or even criminalised by the social mores of the time.

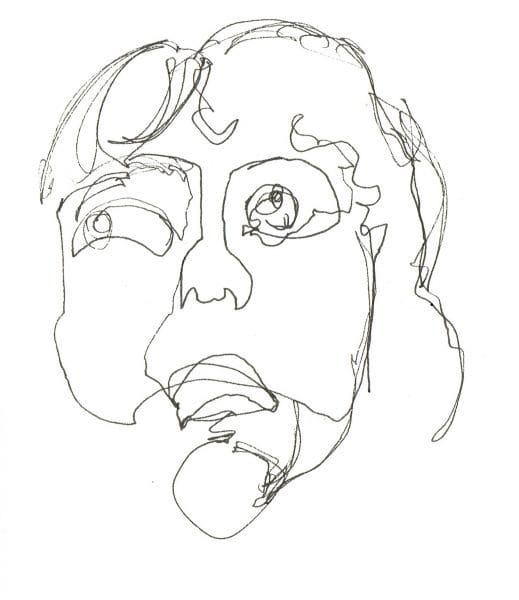

With the goal of re-examining art history in a contemporary queer context, artist Jo Darbyshire has borrowed 13 paintings from the UWA art collection and the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art. Produced between 1900 and 1960 by now-deceased Australian artists, these works form the basis of Darbyshire’s installation in Here&Now20: Perfectly Queer.

The artists whose work Darbyshire has borrowed— including Grace Crowley, Janet Cumbrae- Stewart, Jeffrey Smart and Sidney Nolan—didn’t necessarily have an openly gay or bisexual identity; indeed, their same-sex relationships were often away from public view.

Alongside the borrowed pieces, Darbyshire has placed texts by academics and curators that— sometimes obliquely—reference these sexualities. For Darbyshire, it’s important for queer artists today to know about bodies of work that have emerged in previous generations.

“Institutions have spent so long protecting the reputation of these artists and the reputation of their own institutions, that a lot of people knew behind the scenes that these artists were bisexual or gay, but it was never spoken about,” she says. “So there’s a generation of young, queer artists coming through who don’t even know that these people were gay or bisexual or queer.”

Due to Australia’s conservatism at the time, all 13 artists left for Europe, seeking freedom both for their art and for their relationships. Staying in Australia and identifying their sexuality would have cost them their careers—as well as possible jail time—because male homosexuality was illegal, as Darbyshire points out.

“With the women, even though [lesbianism] wasn’t a criminal offence, they would have been ostracised from society,” she says. “Also, it’s the same as it is now: people didn’t want to be completely labelled [as gay].

“Part of this silence that goes on in the art world about sexuality in general means that these lives, it’s almost too late for us to even known anything about their sexuality.

“It’s so well protected that it’s almost invisible. A lot of these artists, especially the women, were [passed off as] asexual. Like they had no sexuality at all, which of course is very untrue.”

For her part, Darbyshire, a painter herself, identifies as bisexual. She identifies as queer, too, given the moniker encompasses gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual and other identifications.

“But also, after I turned 50, I decided I didn’t have to identify as anything,” she laughs.

Here&Now20: Perfectly Queer

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

29 August—5 December