Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

This article is written by Chari Larsson of Griffith University for The Conversation.

Review: Embodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

Drawing together 19 artists and collectives, Embodied Knowledge: Queensland Contemporary Art is a celebration of women, people of colour and LGBTIQA+ artists. All share a connection to Queensland.

Co-curators Ellie Buttrose and Katina Davidson have presented an energetic and inclusive group show. The conversations are varied and important without collapsing into parochial cliché.

The curators cleverly weave multiple interconnecting themes investigating history, memory and self. Embodied Knowledge gives visual form to the complexity and diversity of contemporary art in Queensland.

At the entrance to this exhibition, you are immediately greeted with Kamilaroi and Bigambul artist Archie Moore’s newly commissioned installation in the gallery’s Watermall. Titled Inert State 2022, it consists of pieces of paper gently floating on the surface of the water.

On closer inspection, each document is a coroner’s report.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, memorials have become increasingly contested terrain, with artists seeking to challenge the very idea of what a memorial might be.

Since the 1991 release of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report, more than 500 Indigenous people have died in police custody in Australia. Moore’s installation is a no-nonsense account of the ongoing racial violence in Australia’s prison systems.

Bitterly, this is a memorial in the present tense: Indigenous deaths in custody have not stopped.

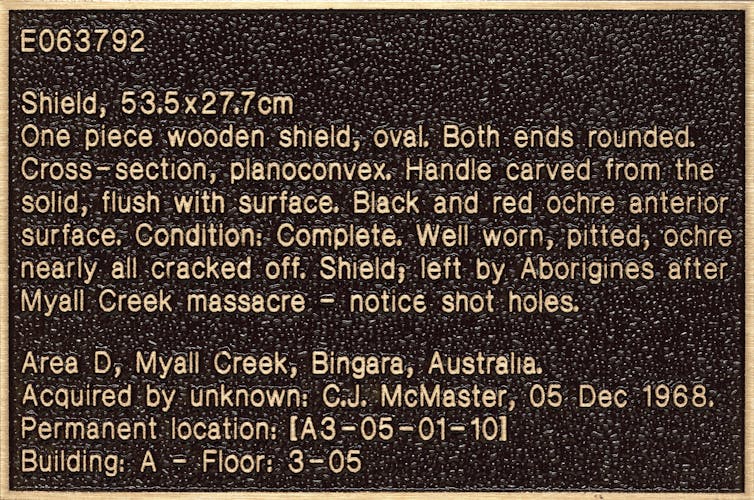

Also working in a counter-memorial mode, Kamilaroi artist Warraba Weatherall critiques museum collections that continue to hold human remains and cultural objects from Weatherall’s Country and its surrounds.

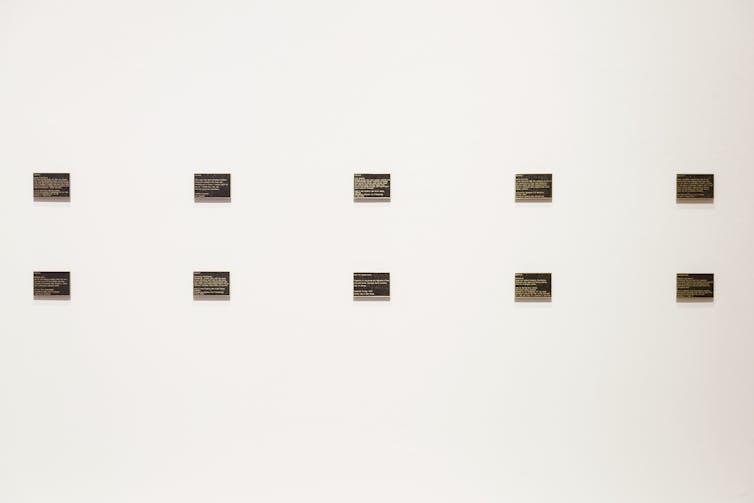

To Know and Possess (2021) is a series of ten memorial plaques cast in bronze. Each plaque is a cast of an original museum record.

The series sits awkwardly, out of scale on the expansive and otherwise empty gallery wall.

This is entirely the point, Weatherall is interrogating the supposed “ideological purity” and neutrality of the gallery space and, by extension, the institutional archive.

He reminds the viewer of the violence collecting practices continue to exert on Indigenous peoples.

It is as if the plaques are deliberately antagonising or waging war with the wall where they are hung.

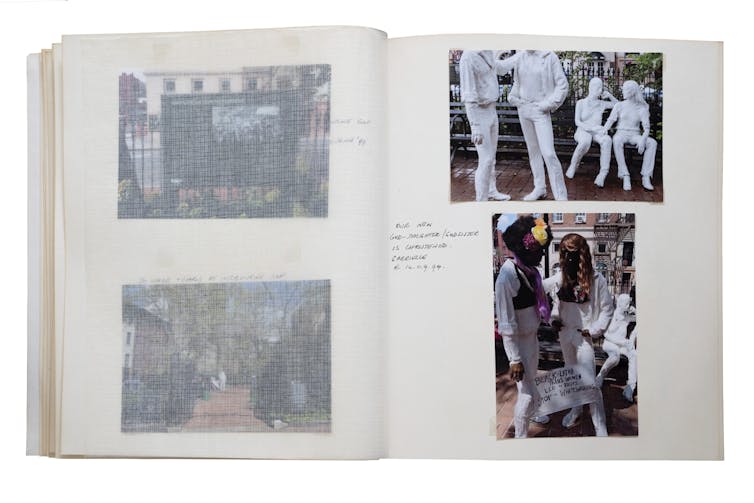

Callum McGrath’s installation emerges from his ongoing research project investigating and documenting public sites that are memorials for the queer community.

Part travel diary, part images selected from the internet, Responsibilities to time (2019) is presented in a series of leather-bound photo albums.

The scale of McGrath’s work is intimate: he invites the spectator to step in and take a closer look. The frosted page dividers frustrate the viewer’s desire to see. Instead, the viewer is left with absences and gaps.

The work is a potent reminder of how queer histories are made invisible by heteronormative history. By working with amateur photography, McGrath is undermining the archive and its claims to authority.

This exhibition cleverly interweaves key moments in the history of native title.

Meriam artist Obery Sambo is from the Torres Strait island of Mer (Murray Island) and a descendent of a long line of master mask and headdress-makers. Here he continues that tradition with his own ornate masks.

In 1898, the University of Cambridge sponsored a team of anthropologists to travel to the Torres Strait, where they filmed Sambo’s ancestors dressed and dancing for ceremony.

Many years later, the footage was used as evidence of cultural continuity in the Mabo ruling in 1992.

Working in an entirely different register, Justene Williams’ installation The Vertigoats (2021) consists of a series of mannequins.

Williams has long been associated with the grunge aesthetic of Sydney in the 1990s. This work is more disco. With their disproportional limbs, Williams’ figures gleefully dance and cavort across the gallery space.

In her sights is the darker side of the online wellness and fashion industries. The idealised fabrication of our online selves is placed under pressure as the mannequins’ elongated limbs stretch to nightmarish proportions.

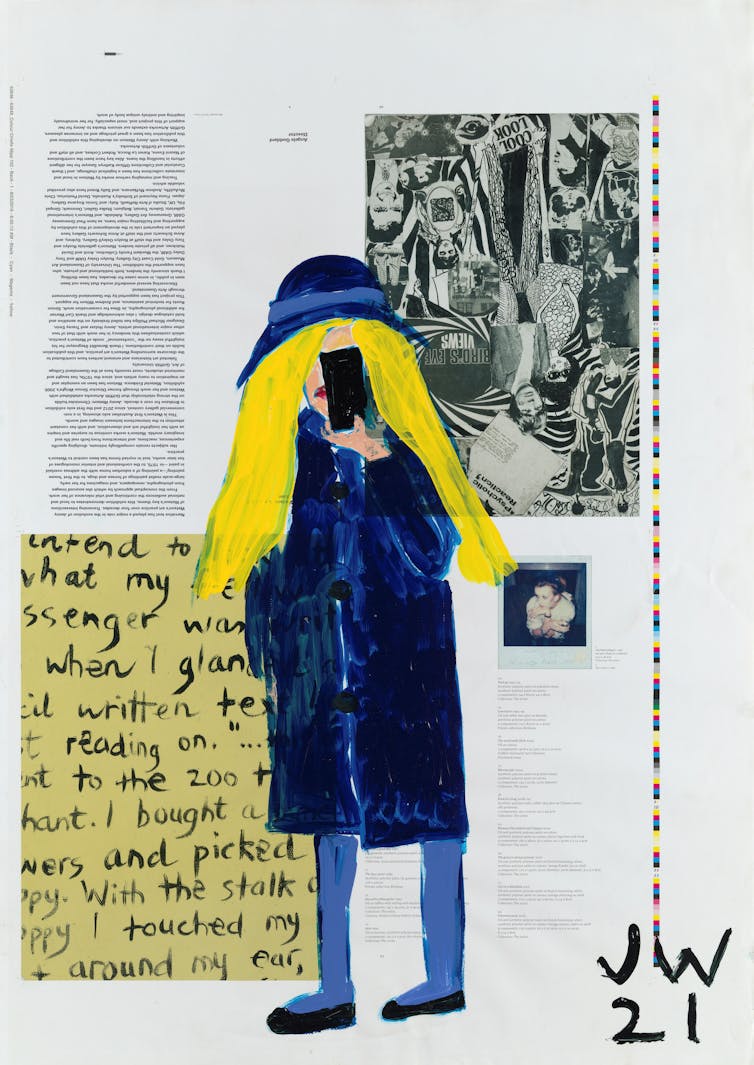

In playful dialogue with Williams’ mannequins is Jenny Watson’s series Private views and rear visions (2021-2022). Comprising of 48 paintings displayed along the length of the gallery wall, the work’s scale is commanding.

Watson has painted over printer’s proofs of the exhibition catalogue for a showing of her work in 2016. This creates a curious fold in time: Jenny on Jenny.

Watson is at her performative best: she places the notion of the authentic self under pressure while working in her distinctly confessional mode of address. Watson draws on recurring motifs that have defined her career, such as the lone woman, horses and the playful incorporation of text.

Embodied Knowledge is on display at QAGOMA until January 22.

This article is written by Chari Larsson, Senior Lecturer of art history, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.