Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

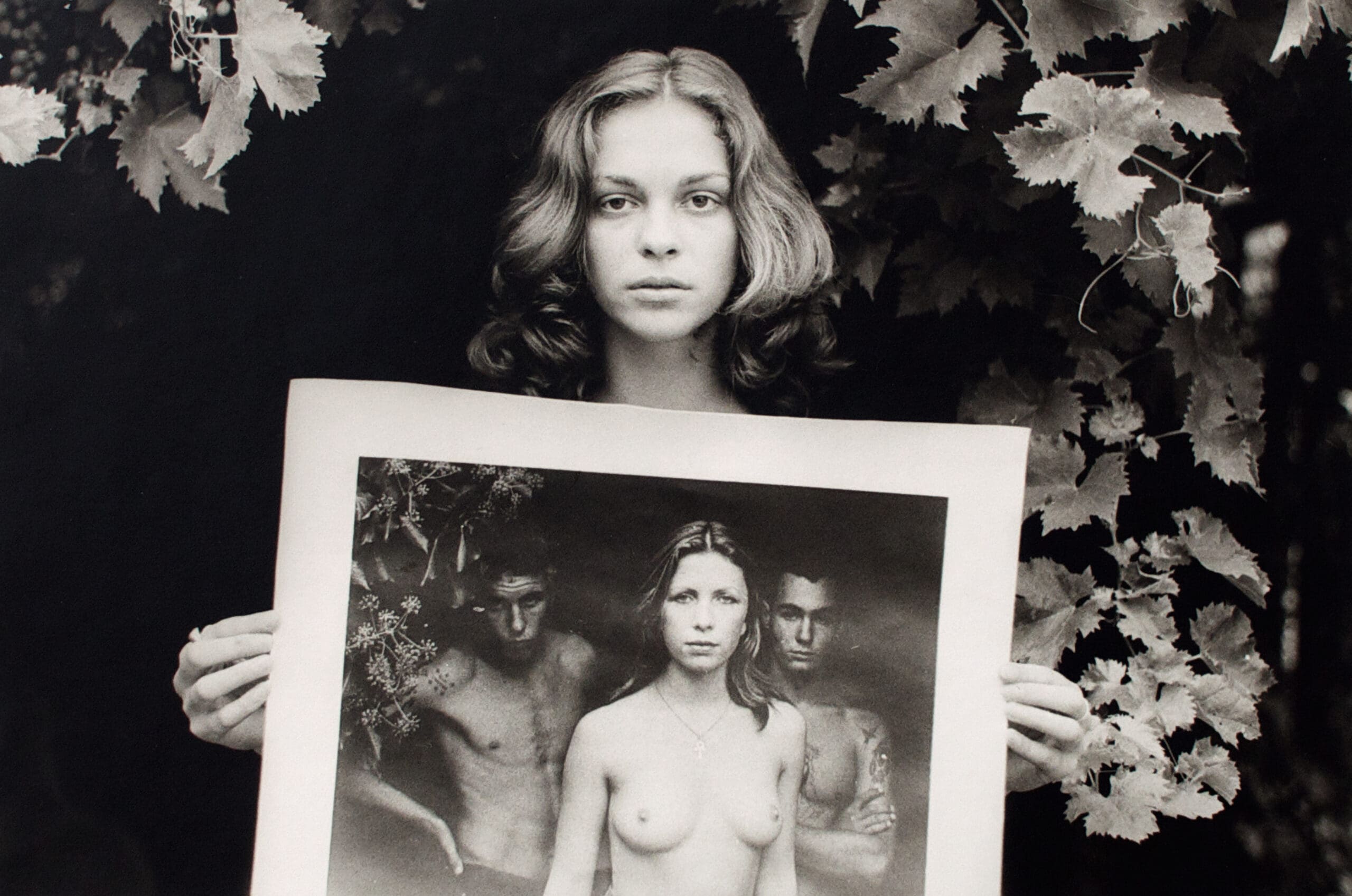

The middle decades of the 20th century were a golden age of documentary image-making. One of the most influential photographers of the era was Carol Jerrems, who has just been celebrated in a major exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Others included Max Dupain, David Moore and Wolfgang Sievers. They were a mix of commercial photographers, artists, photojournalists and war photographers, but were connected by an interest in recording contemporary life.

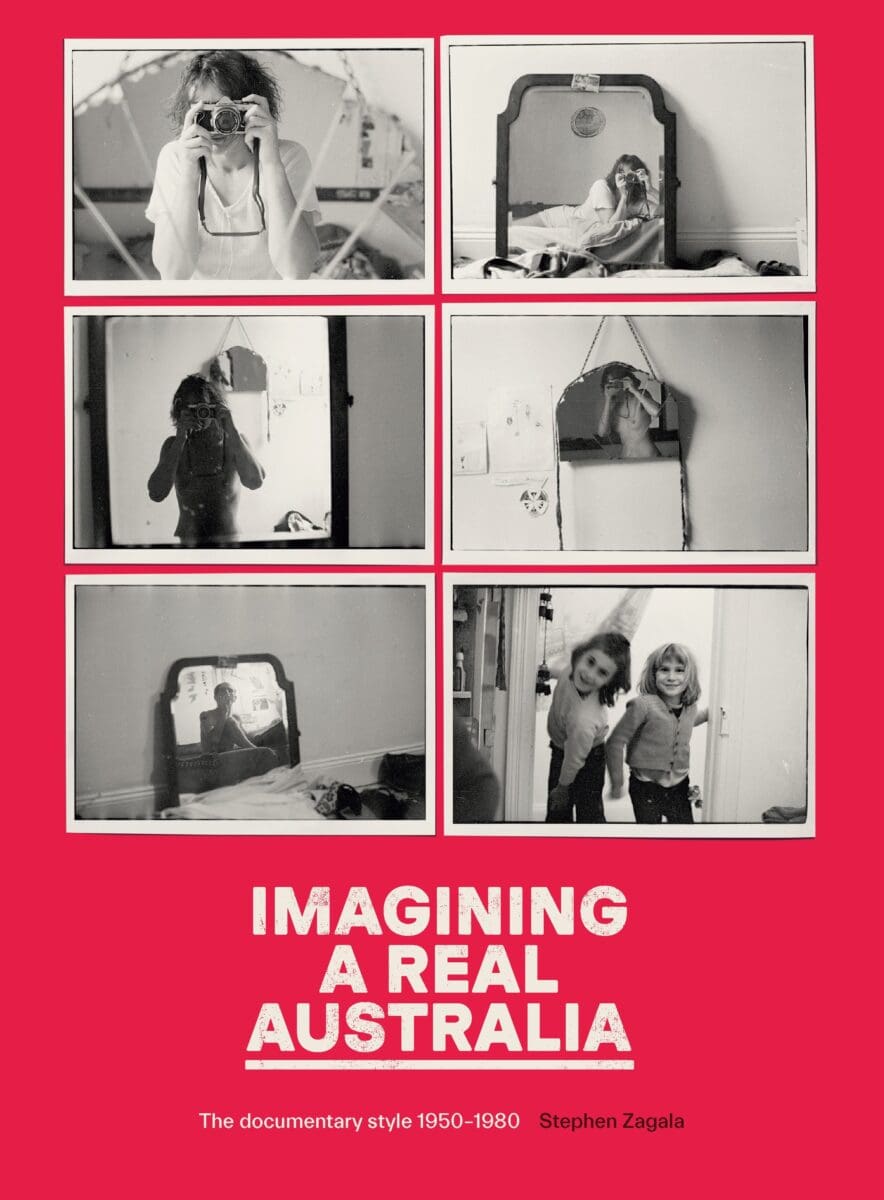

In his new book on the era, Imagining a Real Australia, Stephen Zagala writes that photographs have never been straight records of reality. “The camera composes ways of looking; it constructs perspectives on things,” he argues. Even so, the documentary style that was popular from the 1950s to 1980s was marked by the desire to educate. As Dupain put it, “Factual photography possesses the power to show Australia to Australians.” For Jerrems, it was more about giving and sharing. “This society is sick and I must help change it,” she once said.

Zagala traces the ideological optimism of this style of photography back to the Scottish filmmaker John Grierson, who believed documentary practice could join people in a shared social reality and inspire civic participation. That deep belief in the power of the photographic image to create empathy and social change is hard to square these days. Imagining a Real Australia stops in the 1980s before the arrival of the digital age. It only hints at what happened to our relationship with the photographic image, but the question is a big part of why the book is so resonant today. It’s also because the photographs are so arresting. They engage with Indigenous land rights and sovereignty, labour relations, class divides, poverty, war, feminism, and environmental protest. However wary we might be about national identities in art, these subjects still cut to the marrow of us.

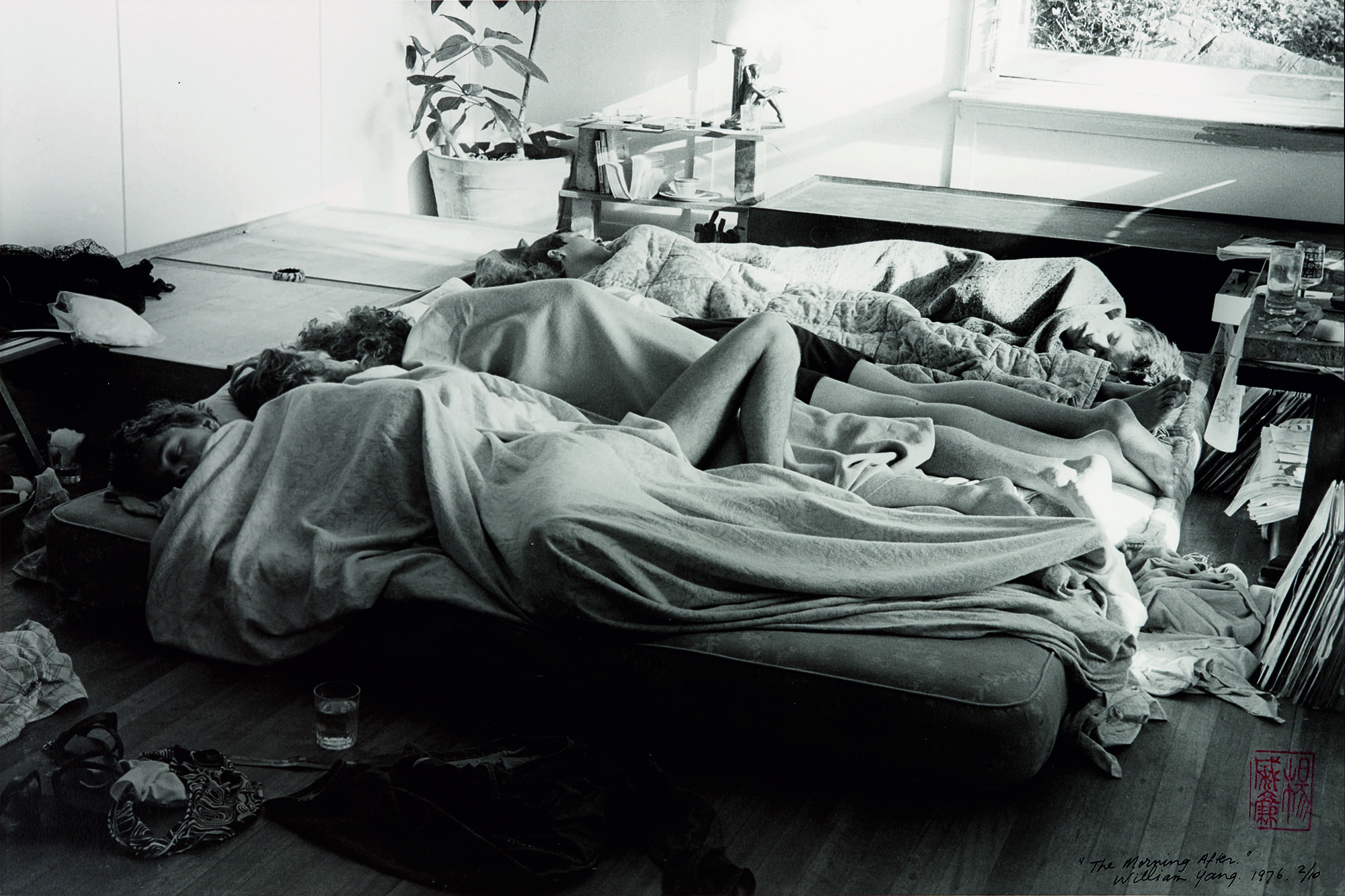

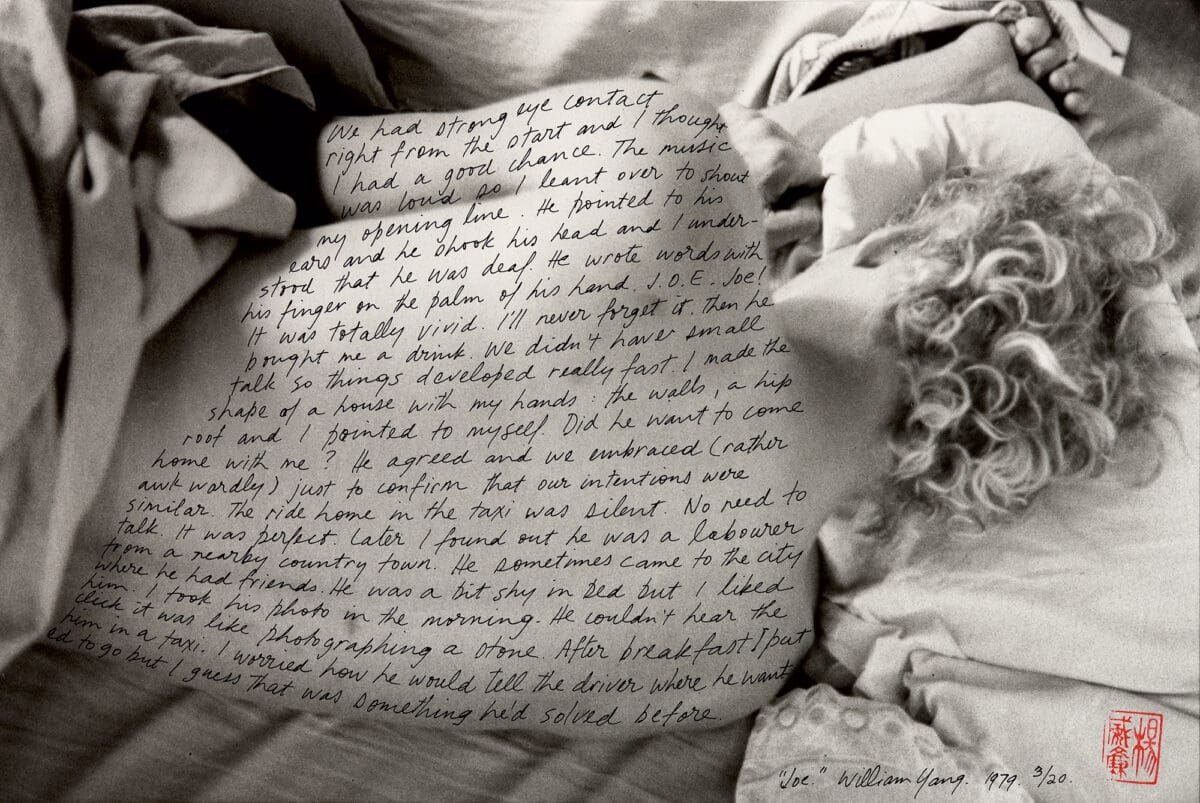

At its best, Imagining a Real Australia is a compelling blend of cultural history, biography and craft. Zagala tells the story behind Robert McFarlane’s introspective portrait of civil rights activist Charles Perkins. He also explores how William Yang captured Sydney’s LGBTQIA+ community over decades, and how Mervyn Bishop, regarded the first Aboriginal press photographer, orchestrated his iconic 1975 shot of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and Gurindji stockman and land rights leader Vincent Lingiari. These moments of storytelling are highlights, though they’re often brief.

Imagining a Real Australia covers a lot of ground, but some longer discussions also thread through the book. One considers the representation of First Nations people as photographers, subjects, and custodians of images. Another looks at feminist practice, including works by Ponch Hawkes, Sue Ford, Christine Godden and Fiona Hall. Hall’s Leura (1974) is a domestic interior, a tightly-composed study of floral furnishing patterns showing an early interest in decoration.

The unfussy layout is a relief. The works are given plenty of room to breathe, and the connections aren’t forced. Together, the images and text set down a concise account of the era. (Many photographers have huge catalogues that are definitely worth exploring further.) Zagala’s interest stays fixed on how images were made, and how they work. He has a knack for explaining technical choices and how different strategies were used to convey particular points of view. He writes about the careful way Carol Jerrems staged the intimacy with her subjects, and how Wolfgang Sievers built his grand visions of halls of industry. He also looks at Rennie Ellis, known for his dynamic and immediate approach, always in the thick of the action.

Zagala’s curatorial and research background shines through here. Photography has always been a bit of a hydra, and he condenses many different strands of practice with ease. That makes it all the more perplexing why one well-known photographer of the era, Roger Scott, doesn’t appear at all. Scott photographed anti-Vietnam war protests at Sydney Town Hall and boisterous teenagers at Luna Park, and also printed Carol Jerrems’s work when she was in Sydney working on the film In Search of Anna. His work was recognised in a 2008 retrospective in Sydney as well as an earlier monograph. In Imagining a Real Australia, Zagala’s attention is clearly on the era’s major moments of change, rather than on listing every active photographer, but the omission is still curious. In the end, it’s a reminder that just like photographers, writers are also making their own careful selections.

Imagining a Real Australia is published by NewSouth Publishing/UNSW Press. You can purchase a copy through the Art Guide Bookstore.