Life Cycles with Betty Kuntiwa Pumani

The paintings of Betty Kuntiwa Pumani form a part of a larger, living archive on Antaṟa, her mother’s Country. More than maps, they speak to ancestral songlines, place and ceremony.

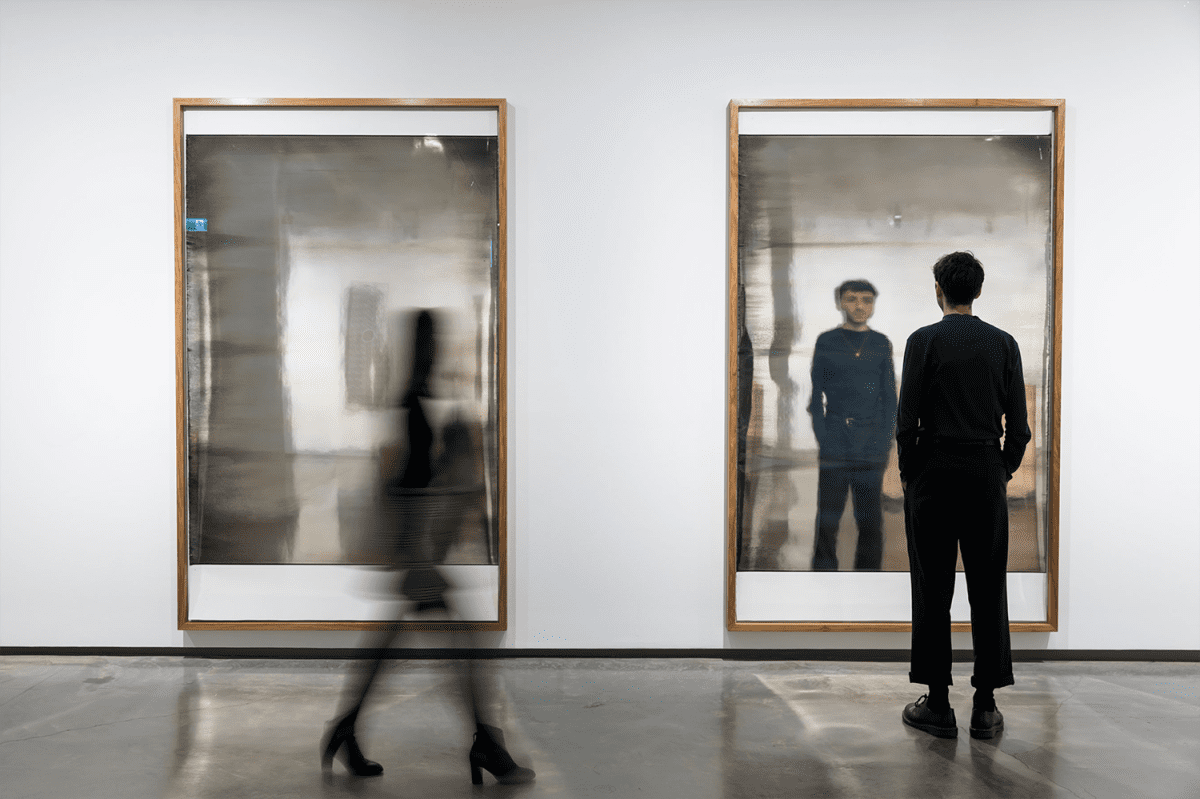

Coen Young, left to right: mirror painting (1); mirror painting (2), 2019. Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019. Acrylic, urethane, silver nitrate on paper. Image courtesy the artist and Kronenberg Mais Wright, Sydney © the artist. Photograph: Anna Kučera.

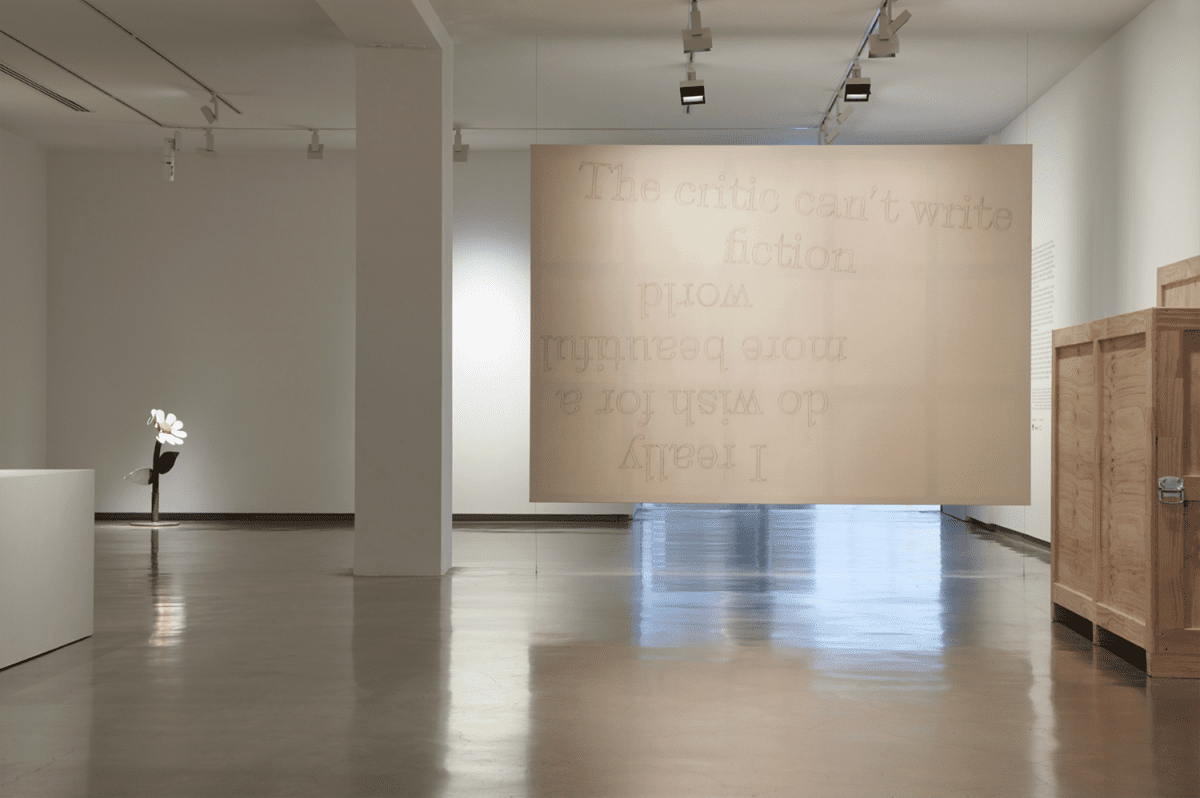

Mitchel Cumming, Companion Planter (host), 2019. Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019. PVC, MDF, heat-shaped foam, hot glue, scenic paint, cable ties, KNULP gallery key, MCA hosts. Image courtesy and © the artist. Photograph: Anna Kučera.

Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019. Image courtesy and © the artists. Photograph: Anna Kučera.

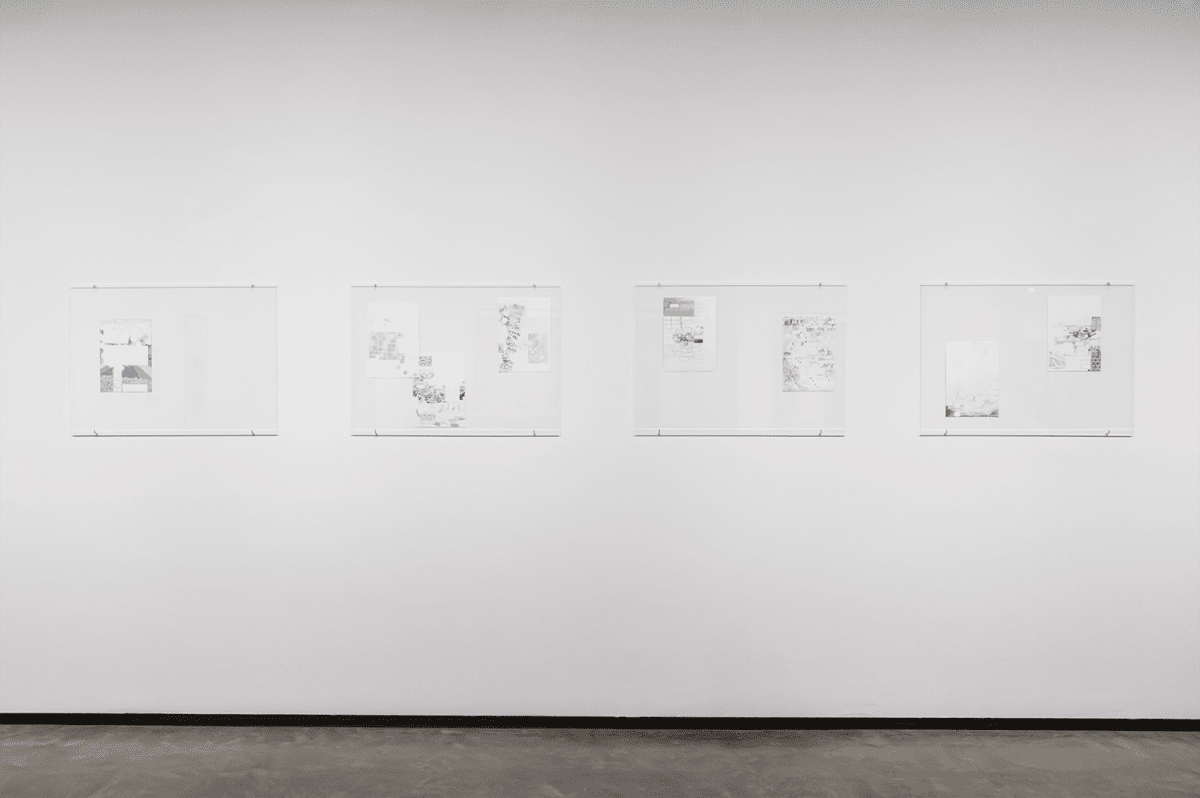

Aodhan Madden, Soluble Rectangles series, 2019. Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019. Gouache and pencil on paper. Image courtesy and © the artist. Photograph: Anna Kucera.

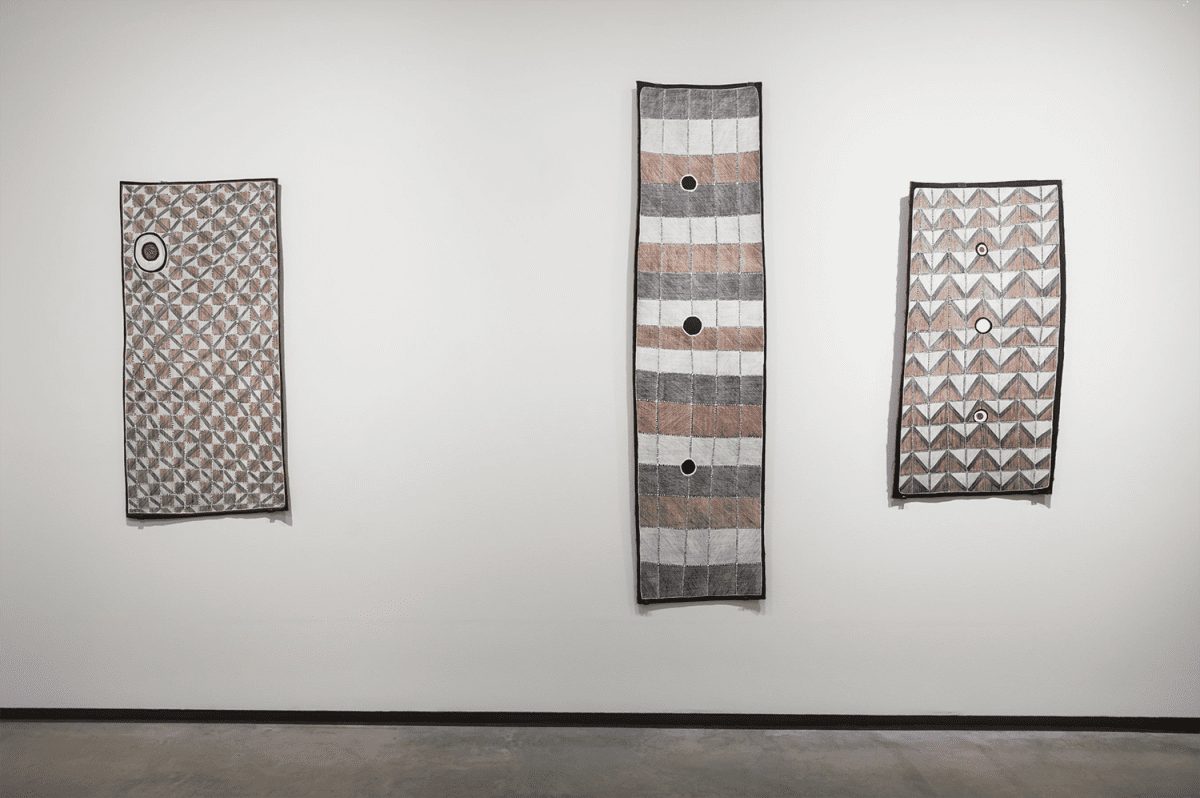

Rosina Gunjarrwanga, left to right: Wak, 2016; Wak, 2019; Wak, 2019. Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2019. Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta). Image courtesy the artist © Rosina Gunjarrwanga/Copyright Agency, 2019. Photograph: Anna Kučera.

Installation view, Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, image courtesy and © the artists, photograph: Zan Wimberley.

I’ve always approached Primavera, the MCA’s annual showcase for artists aged 35 years or younger, less like a novel and more like a box of chocolates. In other words, rather that looking for a clear narrative I enjoy dipping into a mixed bag of treats. And this year’s iteration – curated by artist Mitch Cairns and featuring works by Mitchel Cumming, Rosina Gunjarrwanga, Lucina Lane, Aodhan Madden, Kenan Namunjdja, Zoe Marni Robertson, and Coen Young – offers a diverse range of artworks to whet the appetite.

For me, the highlights include Coen Young’s 2019 mirror painting series. While all artworks are in the broadest sense a self-portrait of sorts, the shiny surfaces of Young’s works on paper reflect the behaviour of contemporary society as well. As I sit on the gallery floor, scrawling in my notebook, I watch visitor after visitor become drawn in by these seductive rectangular pools of silver. And like Narcissus in the ancient Greek fable they are mesmerised by their own reflections. They gaze at themselves in the Sydney-based artist’s mirrored works and shoot selfie after selfie after selfie.

Resolutely analogue and painstakingly handcrafted, Young’s works can be seen as the antitheses of digital culture, yet, like Charlie Brooker’s critically acclaimed TV series Black Mirror, they also critique the mediated nature of our screen-based obsessions.

In Man Who Knows Themselves (?), 2016, Zoe Marni Robertson seems to put a feminist spin on Leonardo da Vinci’s well known c.1490 drawing Vitruvian Man and she asks us to question that old mind/body binary and its entrenched hierarchies.

While the figures drawn by the Sydney-based artist are still male (judging by their exposed and often erect penises), da Vinci’s solitary heroic figure has been transformed into 7 headless bodies who together form a kind of daisy pattern on an equally floral table cloth. And in addition to the standard classification “Homo Sapien (man who thinks),” the artist offers 6 other more deeply embodied categories including: “Homo Economieus (man who manages the home” and “Homo Nullificare (Despicable Man – man who makes nothing);” a reminder perhaps that, statistically, the bulk of domestic work in the home is still done by women.

Lucina Lane’s sculptural work Host, 2019, is a neat manifestation of the fact that artworks can conceal as much as they reveal, and sometimes they demand a leap of faith. In Host, the Melbourne-based artist presents several large plywood shipping crates. These crates, we are assured, contain her artworks. But do they really? With no real evidence to go on we can choose to believe that Lane’s artworks are actually inside or not. Either way this works raises interesting questions.

American artist Richard Artschwager made a number of sculptures out of artwork shipping crates in the 1990s, but Lane’s work brings to my mind the iconoclastic 1961 sculptures by Piero Manzoni in which the Italian artist purported to present 90 tins of his own excrement. Would this famous artwork be more or less subversive if the labels failed to accurately describe their contents? In this piece, as in Lane’s, what matters is the act of faith or the feeling of doubt that the artwork elicits, and the chains of associations that take place as a result in our own minds. Like all good artworks, and all of the works in Primavera 2019, these pieces invite us to interpret them ourselves.

Primavera 2019: Young Australian Artists

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

11 October – 9 February