Coinciding with the Victorian College of Arts’ 150 year anniversary, Presence was a sparse selection of landscape paintings by six notable VCA alumni – Eugene von Geurard, Frederick McCubbin, Clarice Beckett, Fred Williams, Rick Amor, Louise Hearman – interrupted by a video work by Micheal Riley, the late contemporary Indigenous photographer and filmmaker. This curatorial act by the gallery’s director David Sequeira, is a subtle institutional critique of VCA, and an effort to contextualise an indigenous voice within the dominant Australian-Western canon. Personal and vivid, the exhibition forged new relationships between the artworks in the show, and intensified the viewer’s experience of them with a dramatic hang.

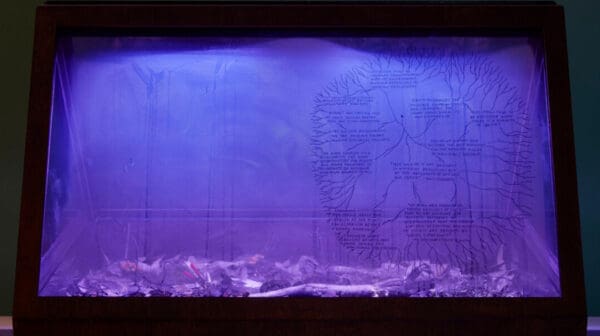

The inclusion of the late Sydney-based Riley highlights the lack of Indigenous graduates from VCA by placing him among the VCA cohorts in the exhibition in a quasi-fictional imagining of an expanded art history. His film Empire, 1997, depicts the parched landscape and sky of Australia that oscillates from the micro to the macro in an epic lyrical montage.The sweeping drama of clouds is paired with the expanse of the desert and close-ups including rain hitting arid land and animal carcasses.These are interspersed with heavy symbolism of missionary Christianity: a burning cross and a Bible floating in water, which are enveloped by the expanse of the environment. An orchestral score by Antony Partos – broken up by bursts of environmental elements – adds to its emotional resonance. The work claims that Western presence in Australia (and in the context of this exhibition, the 150-year history of VCA), is insignificant in comparisons to the Indigenous presence and cosmological view of the landscape that will endure.

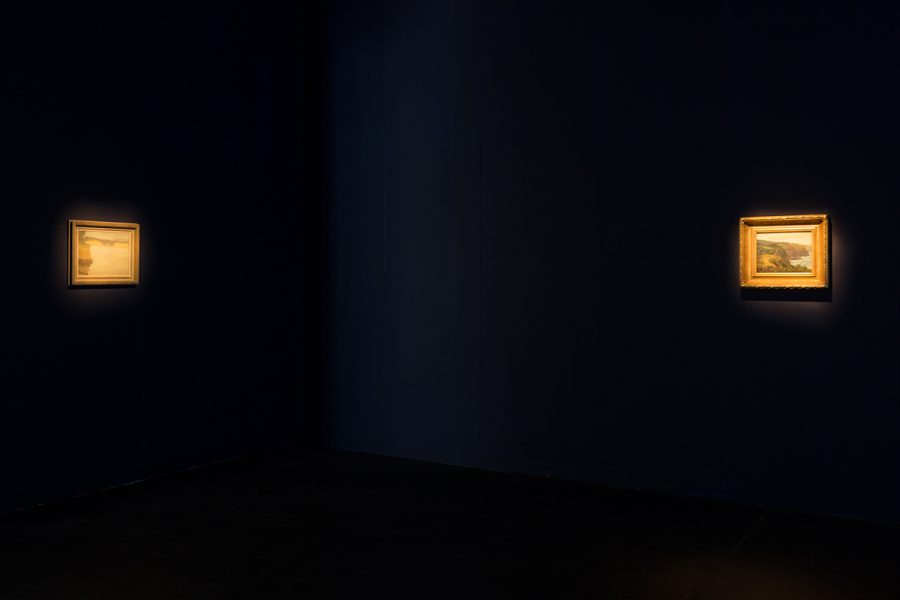

The six paintings – small in comparison to Empire – were punctuated throughout the space and dramatically spot lit. Although Sequiera states that the works selected are not intended to create an overview of “the Australian landscape traditions” they do demonstrate key styles and themes. The dramatic cliffs and sea in Von Guerard’s From below the Lighthouse, Cape Schanck, Victoria,1873, are both a typographic rendering and demonstration of the sublime, Clarice Beckett’s subdued Half Moon Bay (c. 1930) reduces the scene to ethereal pastel tones akin to impressionism, while Fred William’s deft and jagged brushstrokes in Hillside III, 1965, which are indexical to the features of a forest, is an exercise in abstraction. Rick Amor’s scene in his suburb’s street in the ‘magic hour’, Summer Morning Lucerne Crescent Alphington, 2012, is permeated with unease and mystery, emblematic of a suburban melancholic disquiet seen in contemporary Australian artists such as Ian Strange and Bill Henson.

However, the exhibition’s installation opened the possibility of non-linear readings.The dark gallery environment created a sense of suspended time, dampening the idea of conventional art historic progression. Riley’s work subtly dominated with its large scale and central placement at the gallery entrance, and its elegiac soundtrack which bled into the experience of the other works. However, while it critiqued the lack of indigenous voices in VCA’s history, its inclusion did not jar with the other works on show. The overall effect is a forging of new relationships and comparisons. The metamorphosing clouds in Empire wield a power akin to Louise Hearman’s dramatic backlit cloud cluster, which brings to mind both biblical apocalyptic impressions and the cinematic gothic. The filmed details in Empire are photographic abstractions, while the details in the foreground of Fredirick McCubbin’s At Macedon, 1913, show reduction, albeit of a different impressionist kind. Beyond these linkages, the fundamental effect of the works gathered in this exhibition was the creation of cohesive melancholic sensibility: they harmonised with each other through tone and mood, defying easy categorisation.

The effect of the show was made more poignant by its hang, which altered how the viewer perceived the works. In a conversation I had with Sequiera he stated that the way a work is encountered is just as important as the work chosen. In selecting one painting by each artist as opposed to suites, and creating considerable space between them, slow viewing was encouraged. This also created a more empathetic relationship with the works, with close looking akin to the scrutiny with which each artist would have subjected the landscape to. Also, this mode of installation seems further fitting in the social media environment that encourages the quick-fire glancing through the proliferation of timeline images.