Moscow had changed since my last visit 11 years ago. At least, on a surface level.

My itinerary for the Moscow Biennale lists the media preview venue as the State Tretyakov Gallery, no address. After visiting a professor of Byzantinology for breakfast, I instinctively head to the Old Tretyakov gallery by Metro. It’s Monday and it has shut up shop. I confer with a guard but he assures me that there is no function here. How stupid of me. Why would an international biennale be held in this building with its cutesy Russian revival architecture and colourful rooms with icons? I call an Uber, already 40 minutes late for the welcoming speech. The driver gets me as close as possible to the New Tretyakov Gallery which houses 20 and 21st century art.

It’s a hulk of a Soviet-style sugar cube with an eye-wateringly expansive square in front of it.

The topic of the 7th Biennale of Moscow under the curatorship of Yuko Hasegawa, artistic director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and professor of Tokyo University of the Arts, is the age of the Anthropocene titled Clouds = Forests. It promises to look at hot button topics; human impact on the environment, fundamentalism, a world split into tribes where the 52 selected artists have an incomparable role as harbingers of truth. My fellow members of the press pack seem wary. The Biennale, since its last iteration, has come under the ‘support’ of the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation and is headed by an expert council, a dozen names each with impressive job titles.

The official opening of the Biennale is tonight but installation technicians and many of the artists are fervently crawling around darkened rooms, entrances and exits of which are hung with black velvet curtains. Fumbling through black curtains offers just enough time to reset before entering the next room, and the next. Though Matthew Barney, Björk and Olafur Eliasson are the headline acts here, Björk’s works were still being installed.

The first work that first causes me to pause is Marie-Luce Nadal’s The factory of the vaporous, 2014. The fridge-sized machinery creates artificial clouds, using the same process as nature by drawing moisture and air from the room. The harvested clouds are kept in aquariums, some with a monochrome plastic landscape below.

Indian artist Rohini Dasher also impressed with Sphere, 2017, a projection of Japan’s volcanic Mount Aso over her drawings of flat earth and hollow earth maps. The work seemed to bloom as the projection is activated. On a deeper level it criticises Internet lurkers that ignore the world falling to pieces around them, engaging with technology to entertain backwards conspiracies.

Wall-based works dominate the rooms. Video art, much maligned by my husband (“It unfairly demands time of you!”) is a big presence. Ali Kazam’s Safe 2015 to me is the core of the exhibition. The Turkish director has shot the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the most piercing detail. Located on a remote Norwegian island, the Vault storehouses global food crop seeds for posterity (and to preserve agricultural biodiversity). The silent microsurgery performed in removing a stamen is both horrific and beautiful – the vault contains plant life that no longer exists on Earth. The apocalyptic undertones of the seed vault were reflected elsewhere but the title Safe reflects back on the whole of Moscow Biennale. Curator, Yuko Hasegawa, is a safe choice. She diplomatically calls Moscow art audiences “serious” and speaks of Russia in textbook terms, as a bridge between east and west. The works in this Biennale whisper rather than forcefully compel.

As I got to the end of the velvet-curtained rabbit warren, a French journalist approached me. We had become friends quickly over a bottle of Saperavi at a Georgian restaurant the night before.

“The director of Tretyakov Gallery said at the press opening that the Biennale isn’t the stage for politics. I think everybody needs to report that!”

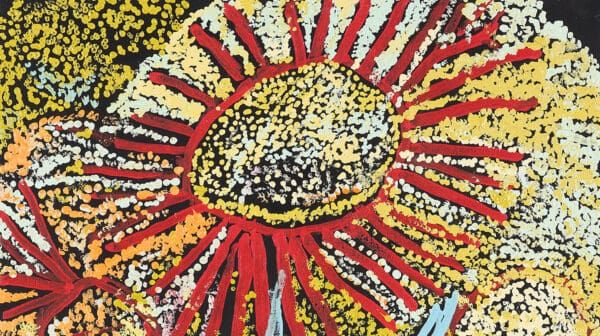

I hadn’t heard it personally but I could see the absence of anything critical of any one government in themes that favoured biology, post-Internet dentity, or in the room full of joyfully naïve paintings by Koji Nakazono.

The loudest works came from the Americans. Young artist and filmmaker, Ryan Trecartin’s hour-long video Mark Trade from 2016 seemed garishly out of place. The title character – covered in makeup, aggressively attention seeking while fluffing about in a desert landscape – is straight out of a cringe-inducing late night Vice documentary.

Towards the end, I came to a room where vacuum cleaners on in reverse were levitating blue balls, the set up wasn’t finished yet and bemused aging Russian gallery invigilators shared a few smirks. Then suddenly without warning, I was thrust into the rooms of the permanent collections, straight into the Soviet Union’s avant-garde. Thankfully, I came to the right landing to see Russian artist, Alexey Martins’ shamanistic animals hewn from Siberian wood, and a babushka invigilator helpfully prompted me not to miss one small sculpture of a kneeling pup on the windowsill.

Back in the sunlight, the flummoxed foreign press sat in the lap of new Moscow at Strelka bar, overlooking the Church of Christ the Saviour.

A German journalist asked his young translator whether that was the church where Pussy Riot put on their infamous show. She shrugged before reaching for her phone to Google it.

Moscow, it is said, doesn’t believe in tears. That show, was clearly put on for the West to admire, the Biennale probably wasn’t.

7th Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary Art

New Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

19 September—18 January 2018