At Isadora Vaughan’s warehouse studio in the industrial area of Coburg North, Melbourne, with her dog Merri in tow, Vaughan creates sculptural installations that sustain a visceral tension between incongruent materials and forms.

In past works she’s used everything from fungal mycelium to beeswax, rethinking how we value certain materials, and how this suggests various political, environmental, and feminist associations—while also being beguiling works in themselves. In our studio visit, Vaughan talks about the economics of art making, her shows at STATION Gallery and Cement Fondu, and using (recycled) plinths for the first time.

Place

Isadora Vaughan: My time at Gertrude studios ended in 2020, and my partner Aaron [artist Aaron Carter] had another studio in Preston that was being bulldozed—so we had to move just before the pandemic. We found here, and this place just works spatially: I need to fit all my stuff, but also work around them [the sculptures]. There are also very few affordable studios. I mean, sometimes I can’t even really afford this, but you make it work.

We have a few studios here; we built the walls ourselves just by salvaging materials. It made sense for us to find a place we could share with friends; I believe in that sense of community. And there’s a real need for longevity. We have 10 years here, but that’s going to go so quickly. Sometimes it’s busy here and sometimes it feels like you’re screaming into a cupboard by yourself [laughs].

Process

Isadora Vaughan: I’ve always tried to have a consistent presence. Even during my pregnancy, I liked to work. This is my job, it’s like nine to five; I’m not a night person. At the moment I’ve sometimes been starting at six o’clock in the morning, before the baby wakes up. Sometimes I’ll work longer if I need to, but with looking after a baby, and enjoying cooking way too much, I like the ritual of the end of the day.

“I often have this process where I’m repurposing old work, like literally melting down something to make something else, which is also a political decision.”

I always make from what’s at hand or financially doable—although I do believe in spending money when you need to. Mostly I work by doing things myself: I weld, make things out of clay, cast things. In my relationship with trades, there’s some friction in that I really love asking people how to do things, but I often get to a point where I’m like, “I can’t do it the way you’re telling me to do it.” I end up doing my version, which can be generative: you can come to an outcome that you wouldn’t otherwise. When I went to art school, my teachers Simone Slee and Bianca Hester were very encouraging to do things materially, to figure out what materials were and how they worked.

I often have this process where I’m repurposing old work, like literally melting down something to make something else, which is also a political decision. And I have horticultural knowledge and I’m really interested in how different plant systems work; how things evolve in certain environments. While it’s a cliché, I really do work through the process of making. I also make things because it’s my sense of freedom. You have to believe in what you’re doing enough to even do it.

Projects

Isadora Vaughan: I’m trying to bring disparate forces, textures and feelings into one show. I want it to have a certain speed and materiality, while also problematising any essential idea or monument. It’s like a healthy ecosystem. For STATION, the impetus, or the point of tension, was when Aaron brought home thrown out plinths from the recent Barbara Hepworth show at Heide [Museum of Modern of Art]. I’ve never used plinths, so it feels a little hilarious, but it’s also allowed me to make small works, and spend time understanding Hepworth’s process and shifts in scale.

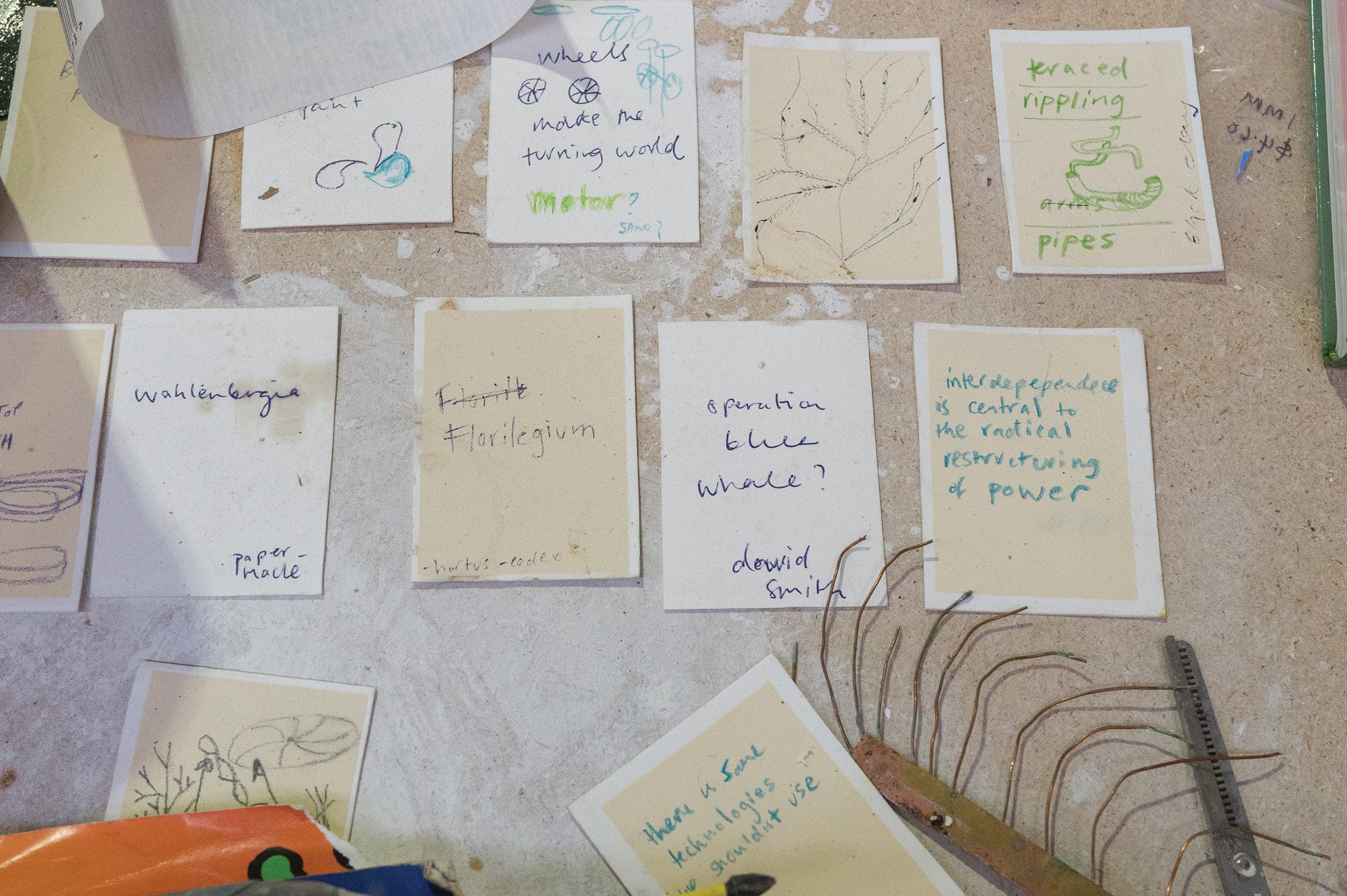

I started making small wheels, which is a symbol that I’ve used in my work before; a link between nature and machines. It’s this idea of domination and gathering harvest, and there’s something about the analogue nature of it. I also spent time at the herbarium, researching different modes of classification and value. Walking along Merri Creek to the studio this time of year, the wahlenbergia [flower] is so beautiful, especially before the wattle erupts. I knew that I wanted to have the wahlenbergia [in the sculpture] after learning about its colonial distribution. Different specimens were taken from throughout Australia and New Zealand, some ending up as novelties in rich Parisian palace gardens, after months on ships!

With the materials I work with there’s a kind of ready-to-hand element, as well as a deep process of finding connections and meaning from the place I am working within. So I’ve got these copper wheels and different local grasses—and then I’ve bound them with the intention to preserve their erect form, which would otherwise wilt as it dries out.

This shifts into the diorama made of hollyhock wood that grew in my garden a few years ago. It’s been dried and then I’ve carved the surfaces: it’s very orchestrated. And I’ve placed it with kangaroo grass, one of the oldest food sources of First Nations Australia. And there’s themeda triandra, also from my garden. I’ve intentionally coupled introduced and Indigenous species.

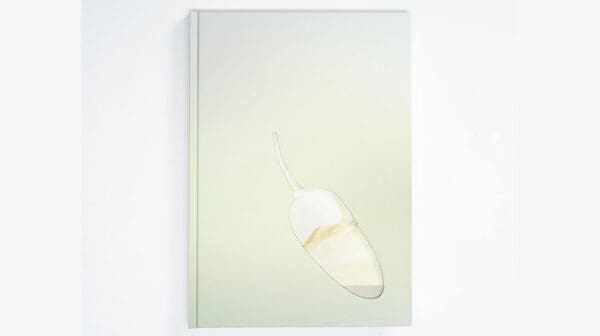

That shifts to these ceramics, which are the enlarged internal anatomy of the wahlenbergia, a giant version of what’s inside the small flower. Then there’s the plastic [sculptures] which have an essence to them, especially in contrast to other parts of the show, which are much slower and more porous. It’s this shift between the miniature and magnified. All these parts speak to each other. You can’t ever really contain things; it’s like my politics and interests are always overflowing. For Cement Fondu—it’s a 2016 work for which I’ll have to regather the parts, and then also make new parts. But I like this kind of problem solving while also using what’s directly around me. Your politics as an artist are always important, but there’s also something wonderful when the work has a language and life of its own.

Rumours of True Things

Isadora Vaughan

STATION Gallery

(Melbourne VIC)

7 October—4 November

Better Nature — Earthen

Group exhibition

Cement Fondu

(Sydney NSW)

14 October—3 December

This article was originally published in the September/October 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.