Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

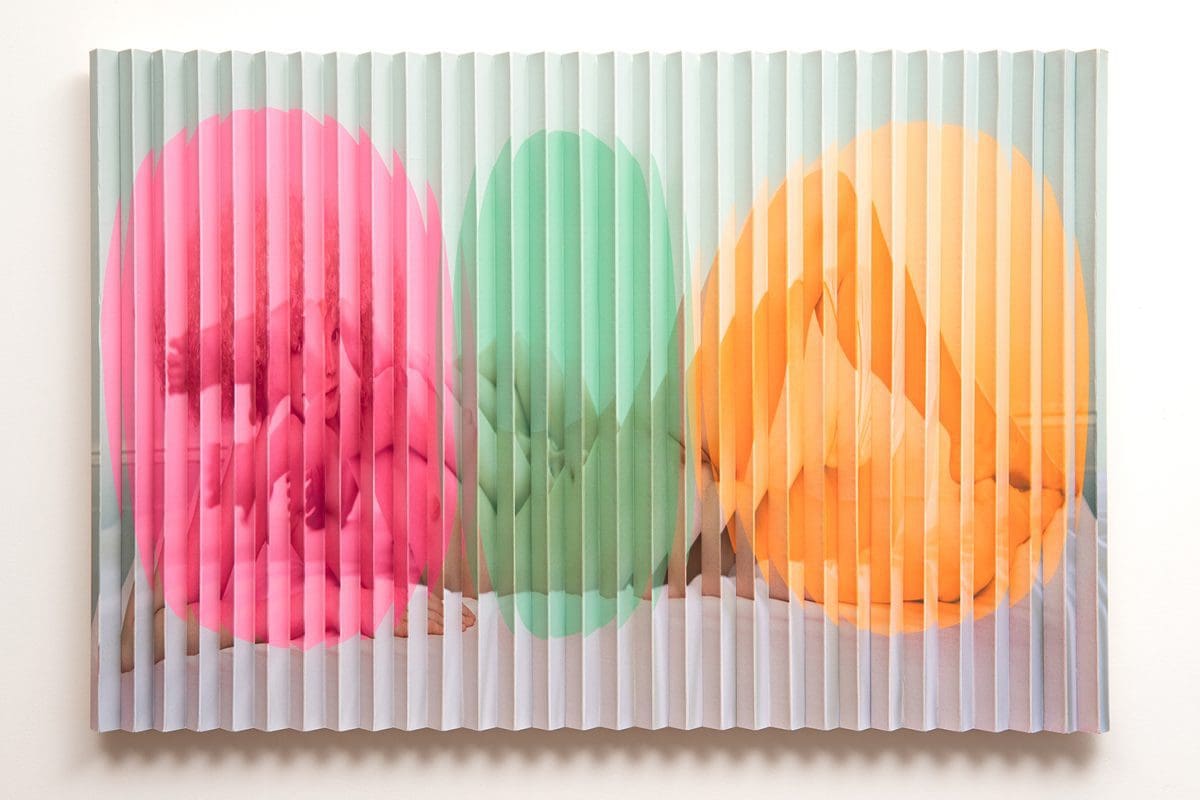

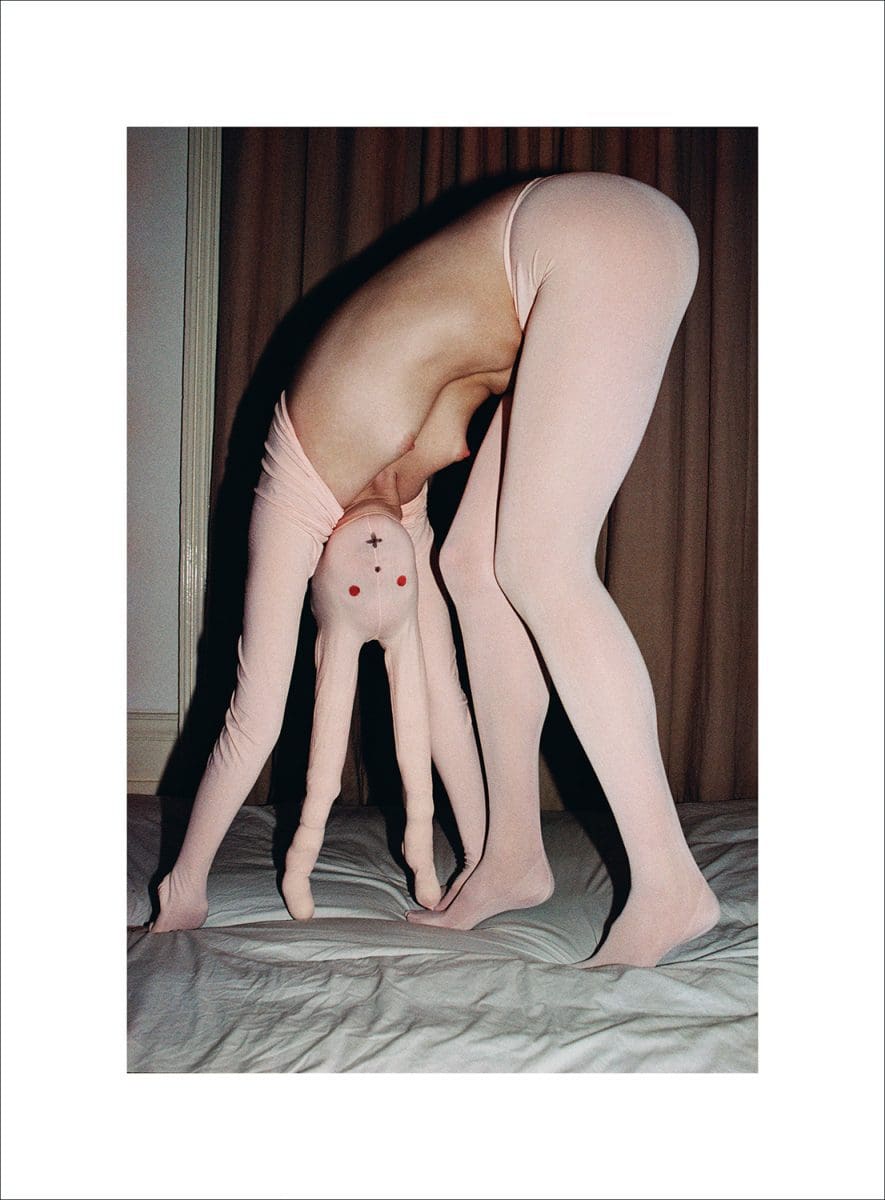

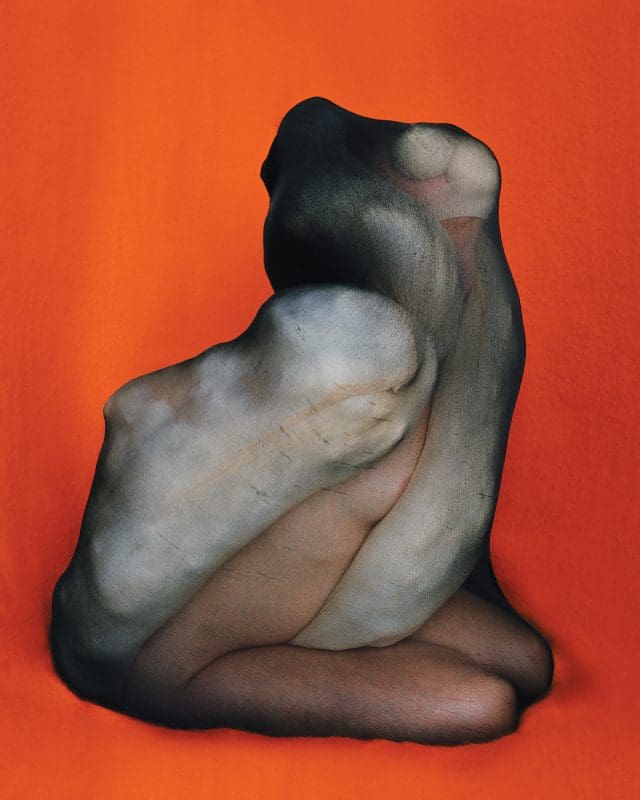

Intimate, sexualised, playful, primordial—these competing adjectives describe the abstract, almost sculptural, photographs of Polly Borland. For three decades Borland has used photography as her medium, creating images that are compelling in their abject nature. Born in Melbourne, Borland spent two decades in London photographing for publications like Vogue and The New Yorker, and famously capturing Queen Elizabeth for her Golden Jubilee in 2002. Eventually the artist shifted more fully into her artistic output and she talks about this move, as well as photographing people in power and the influences on her work.

Tiarney Miekus: Do you remember the first time that you intentionally took a photograph?

Polly Borland: I don’t know if my memory is correct, but the first sessions I remember doing was when I was in high school in year 12. I was taking photos of two of my sisters in my bedroom, and that was an intentional photoshoot. Whether it’s the first intentional photograph—I don’t remember taking photos as a child, although I’m sure I did.

TM: Was your family interested in art?

PB: My father was an architect, and he was an extremely creative modernist architect. We were brought up in an arty family. My mother loved art and we were introduced to furniture designers and artists, and we were aware from a very early age about aesthetics—my father had specific furniture, designed furniture, in the house. We also went to a progressive, creative school, Preshil.

TM: A few people I know who went into fashion photography often had fashion or domestic aesthetics as a core relationship with their mother. I wondered if that was the case for you?

PB: Well, my mother was really into her own clothing. She definitely followed fashion and had a lot of Australian Vogue magazines in the house. I remember being quite interested in the Vogue magazines, but she was very into French fashion, Italian fashion. She was very particular in what she wore. So, I was definitely aware of fashion, but that’s not really why…Well, it’s partly why I tried fashion photography, but it was more a suggestion of a tutor at Prahran College where I did art photography school. But in a way I regret that because it took me away from what I’m interested in: which is my own work. I always wanted to exhibit my work and that’s ultimately what I’ve ended up doing, but it took some years to get back to the original intention of my photography.

TM: You moved to England in the late 1980s, and it was a small struggle to get a break with your photography. How did you see it through?

PB: It was very hard because I had my own business already in Australia. And I wasn’t that young, I left when I was 28 [years old]. But I knew that ultimately it wasn’t going to be satisfying for me in Australia. So, I left, and it was three years of struggle. I think what happens to a lot of people that leave, they don’t get that it’s going to be difficult, and they don’t have the staying power. There were so many times I wanted to give up and my husband kept saying, “No, you’ve got to keep going. Everything’s about perseverance.” Which it is. And so that’s what I did. I worked as a waitress, as a kitchen hand, which I’d done when I was at college in my early twenties, but to be doing it again at the age of 28 was not fun. I hated it actually. It really took me three years before I got a proper break, and then I became a resident portrait reportage photographer for The Independent Sunday magazine, which was considered extremely photographic. They were employing the best photographers in England, and I got a really good reputation from that. And that led to the exhibition Australians [celebrating Australian ex-pats] at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

But in the end, I left portraiture and commissioned work because ultimately portraits are quite restrictive creatively. Even though I loved getting a window into somebody else’s life, it was quite high stress because normally I was not the one that I was pleasing. Now I’m starting to photograph myself anyway, so I don’t have to worry about anyone any more. I can just be me. A camera and me.

TM: That reminds me of when you once said that photography “allowed you to see the world, but also to control it and make it feel safer.” What makes it feel safe?

PB: For me, it’s better to be in control than out of control. What I meant was that I can point my camera anywhere and reorder my life by framing stuff out. Photography can be used as an editing tool as much as anything. It wasn’t necessarily that I had control over my subjects, but that I had a certain amount of control over the placement of objects and people. It’s not a psychological control, more a visual control. And the safety aspect is that it’s about perception. But as I’ve gotten older I’m not really interested in controlling, because we’re all sort of screwed as far as I’m concerned. I mean, what can I control? The world is in the midst of the most awful chaos and our politicians are not doing what they need to be doing to protect us. I’m talking about climate change.

TM: Do you want to push your work somewhere ecological or explicitly political?

PB: I have never really viewed my work as political, but I think it probably is. A lot of women think that it’s political from a gender perspective, but I’ve never thought of it that way. I just do what I do. And I’m sure a lot of the things that I’m interested in are fed into my work. It comes out by osmosis, almost. But in terms of climate change, no. I just want to do interviews and talk about how screwed up everything is. I’m passionate, but I also feel totally powerless. I’m kind of a bit lost, to tell you the truth.

TM: I think it’s a common feeling, but on the subject of power: as someone who’s photographed people like Donald Trump, former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, and Queen Elizabeth, do you feel any sense of immense power from them?

PB: Yes, I do really. Look, I am not a royalist, but with the Queen I was quite taken aback at my reaction because I was really overwhelmed meeting her. And I think it was because in Australia when I grew up, it was the English colony and everywhere you looked at school, in a doctor’s office, everywhere, there was always a photo of the Queen. So, I was very overwhelmed meeting her, but she was actually rather nice. Trump was extremely manipulative, but very generous with his time. But he was manipulative because he knows how to work people. I took that photo in 2000, so at that point he was who he was—which is actually, as we know now, not a very nice person. And Berlusconi—that was kind of scary because that was in the prime minister’s palace. And it really was like a palace. It was old Italian, very ornate. And he was very intimidating actually. You felt like you were having an audience with a mafia boss. But I loved photographing the politicians because I’m very interested in politics obviously, and I really did have a thing for photographing people in positions of power. But I don’t know how I feel about it now, though.

TM: Can we talk about your more abstract works, many of which feature people in these organic, sculptural shapes, which stockings are often key to forming. Where did the idea come from to use the stockings?

PB: I was aware of other artists that we were using stockings, but with Gwen [Gwendoline Christie, the model in Borland’s series Bunny], we started this whole body of work and it was based on photos of pin-up girls. Gwen is really tall and not really androgynous: she looked like a 50s starlet, so I wanted to do a series of pin-up photos of her. The more we went down that path, it morphed into ‘let’s dress her in animals that are associated with women’. There was a cat, and then we thought of a bunny. I went to her place one day, and I decided to draw on [a bunny face] with lipstick and eye liner, and I bought some tights to make bunny ears. So that’s how the stockings started in the Bunny series.

TM: With your abstract works, they feel simultaneously sexualised, playful, childlike and primordial. I know you’ve talked about these different aspects, but why does that overlap compel you?

PB: I’ve tried to analyse this and I have no idea. When I was at college, Diane Arbus was my first love in photography. I was blown away by her photos. They were obviously people living on the fringe and very unusual characters, and it struck me how brave those photos were and also how people have criticised her [Arbus] for being cold and anthropological almost. But for me, I think there’s a huge humanity in those photos. It’s the simplicity of them, the directness of the gaze, how close she gets to people. I don’t find her photographs judgmental in any way. And I got a lot of ideas for my reportage life in London.

But also, when I was at college, I got introduced to Larry Clark whose work was very frightening to me. It was like, “Oh my god”. It was a world that I was on the edge of anyway: it was the punk scene, and it was musicians, artists, everyone was sort of mixing—criminals, too. And there were a lot of drugs. So I was aware of that going down then [Melbourne in the 1980s]—but I didn’t really feel part of that. Then when I looked at these photos, I just remember seeing they had black and white spot marks, so they hadn’t even been retouched. I was blown away that firstly, anyone would photograph that stuff. And second, it was shocking. I remember thinking: I’d prefer to be moved in this way, which was a more dramatic way of moving someone than just beauty. I’m not saying that the sexual stuff in my work is deliberately aimed to shock, but I think the combination of Larry Clark and Diane Arbus made me realise that there was no censorship. I think that’s why a lot of people find my work very disturbing. I don’t know why, because I don’t find it disturbing. But I suppose with your question—I was quoted in one interview as saying, “Well, sex is what everyone thinks about most of the time.” I mean, not really, but it is a great preoccupation of human beings.

TM: During your practice people’s relationship with images has intensified. What do you think about the acceleration of images, especially with the internet and social media?

PB: I think it’s devalued photography. And music, too. You can get anything for free. I think it has had a destructive influence, and recently I’ve gone off Instagram. I’m done. I don’t know that it’ll be forever; it’s a good selling tool, it’s good to advertise exhibitions and show off, but I just got tired of it. On the whole, it’s exhausting and soulless, and I’m bombarded. It doesn’t make me feel good either. I’m trying to paint now, and I follow mainly, in the latest part of my Instagram use, painters. And a lot of young painters. But I’m also like, “I’m trying to paint, I don’t think I’m very good. And I really need to figure this out without watching what everyone else is doing.” You see through Instagram that a lot of people are doing similar things, and the idea that you could forge something individual or even original, dare I say it— it’s pretty slim chances.

TM: The iconic image of Polly Borland is of you adorning oversized glasses—how did that become part of your personal aesthetic?

PB: I don’t really know. I started wearing glasses in my mid-thirties and over time I realised that bigger glasses suited me better and, you know, why not? I’ve got a bit of a shopping addiction which I’ve tried to curb, but I’ve collected a lot of glasses. The problem is that my eyesight keeps deteriorating, so I keep needing to update all of the prescriptions! Also, my mother wore big sunglasses and she looked fabulous in them, in the 70s and 80s. Ive just always liked big glasses and they suit my family.

Melbourne Art Fair

Polly Borland at Sullivan+Strumpf

17 February—20 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.