Jazz Money is a poet and artist of Wiradjuri and Irish heritage and Neika Lehman is a writer descended from the Trawlwoolway peoples of north-east Tasmania—and poetics is central to each of their practices, as their illuminating conversation attests.

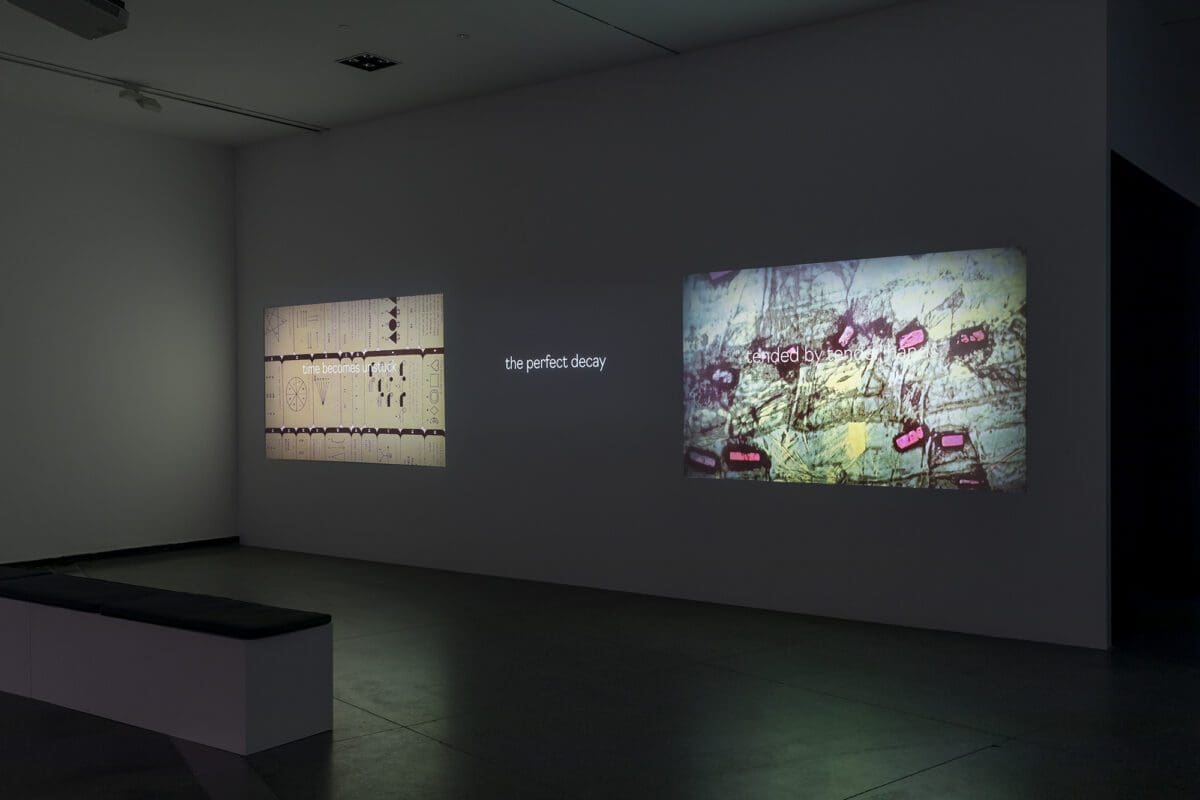

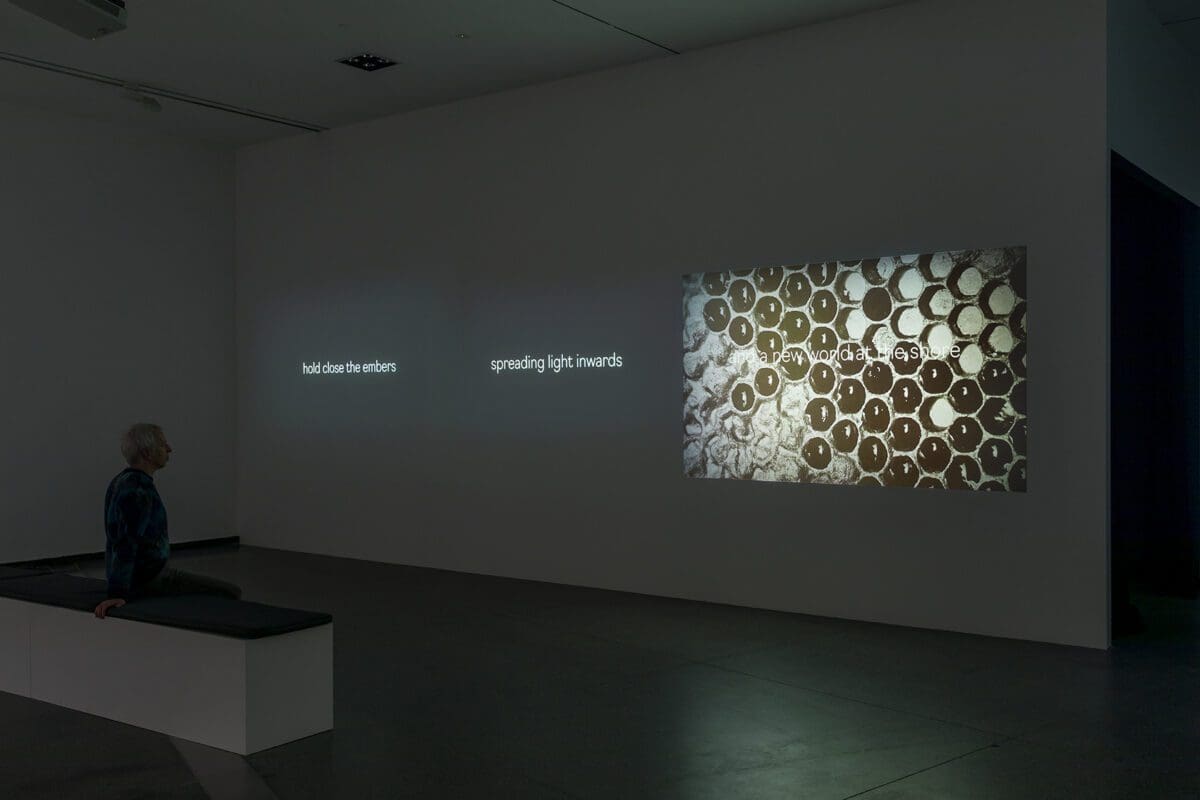

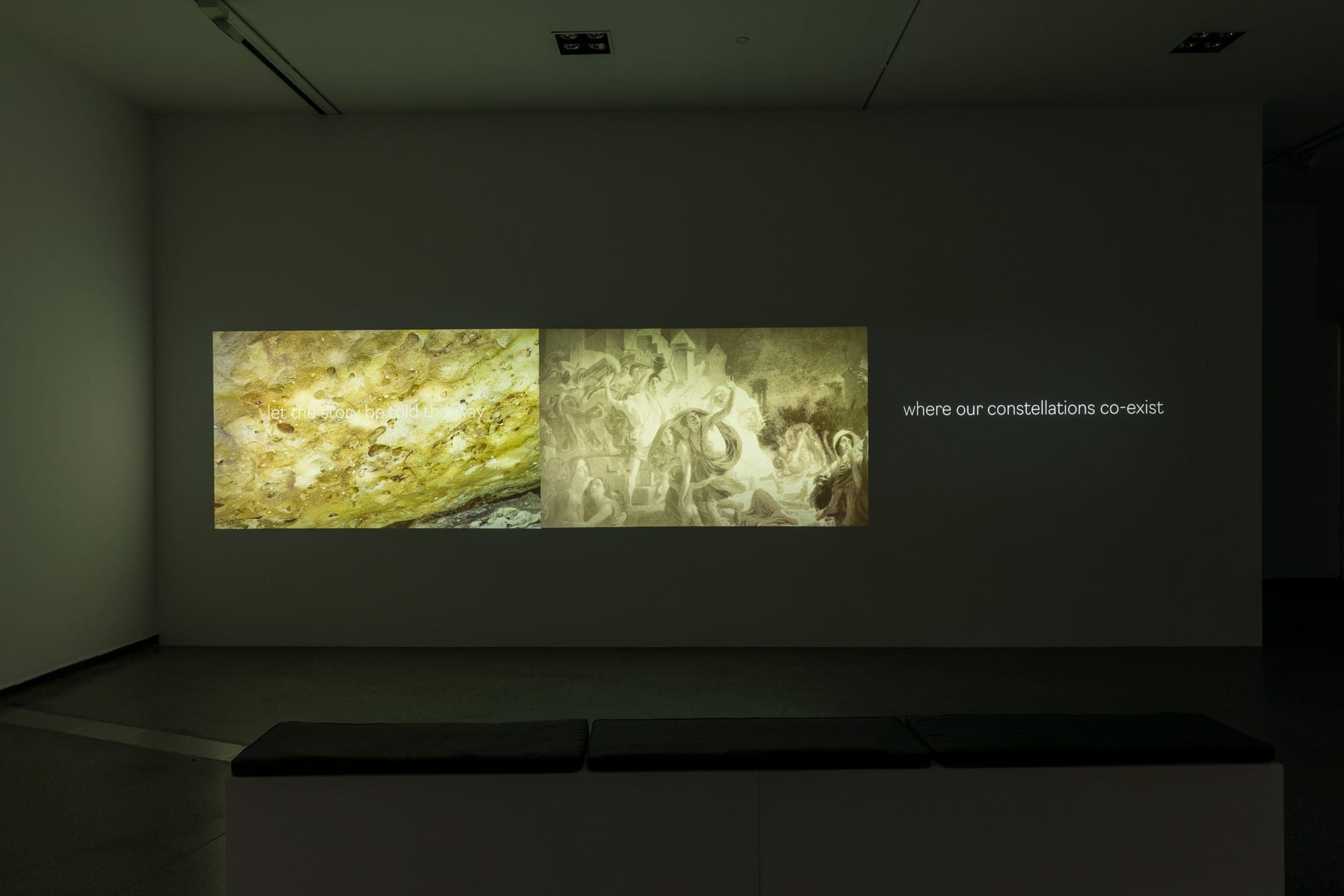

Lehman talks to Jazz Money about working between poetry and film, focusing on Money’s newest installation, Infinite Iterative Piece. The three-channel work is an evolving audio-visual poem that randomly allocates archival images with ‘lost lines’ and phrases from Money’s notebooks—and the work sits within the group exhibition Between Waves at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.

Money and Lehman speak about how this evokes something within the exquisite corpse method (a collaborative mode of drawing or creating first used by the surrealists), while also talking about logic and mystery, and how the precise convergence of image and word leads to meaning making.

Neika Lehman: You have an expansive practice, but this new commission for Between Waves returns to your twin strands: poetry and film. What was it that interested you in these forms initially? And how are you feeling about them now, several years into professional practice?

Jazz Money: Filmmaking is my first love, but as poetry has become a greater focus in my creative work, I often find myself wondering how to bring these forms together. I see a great sympathy and relationship between poetry and filmmaking, particularly film editing: both take a pre-existing language or set of images and arrange them in complimentary, contrasting or contradictory ways to communicate something to an audience. And in that pairing, you create a third space where new knowledges are revealed.

All my favourite film editing does that: compares and contrasts; surprises you in the imagery that it chooses; the way that pace lures you in, or pushes you away; the way that narrative and imagery come together to communicate the message in a way that is understood bodily. All my favourite poetry uses the same tools.

It’s exciting for me to bring film and poetry together in this commission and to keep pushing the forms I love. Infinite Iterative Piece also features a beautiful score by e fishpool which brings the elements together in a way that feels quite captivating and complete.

“I really struggled to describe the work in abstract! Digital exquisite corpse was the closest I came to putting to words a work I have been wanting to make for a while.”

NL: As a fellow poet, I definitely resonate with the way you describe the raw material of the poem or film as having a kind of unruly autonomy that exposes itself when you edit. The material teaches you in the editing process, not the other way around. And this “third space” you speak of, it’s a place of great sensitivity; of logic and mystery. Sometimes it can feel overwhelming, how much the universe of meaning rests on what word goes with what image or feeling.

This new commission you’ve made, Infinite Iterative Piece, lets the raw material really take centre stage in what you are calling a digital ‘exquisite corpse’. This three-channel work is an evolving audio-visual poem that randomly allocates archival images with ‘lost lines’ and phrases from your notebook. When I’ve played exquisite corpse, people usually play with either images or words. This artwork combines them. Did you experience anything surprising about this audio-visual collage?

JM: I really struggled to describe the work in abstract! Digital exquisite corpse was the closest I came to putting to words a work I have been wanting to make for a while. In a lot of ways, it feels like a form of play and surrender, to let the lines roam free. Watching the three screens, I’ve been really delighted by a hypnotic quality that reveals itself as you wait to see the different combinations of how text and image will come together, and what insights can be gleaned from the randomised combinations. It’s been a brilliant way to bring new life to old ideas and to see new pathways revealed for the writings.

NK: In that sense this piece is quite affirmative: to have trust in the process itself and to not ever fully abandon old ideas! It’s interesting—even if your ‘exquisite corpse’ allusion is more descriptive than definitive, your emphasis on play and hypnosis still has surrealist origins, like the game itself. It also reminds me of Tristan Tzara’s Dadaist poetry method, where the poet takes a newspaper article, cuts out individual words, jumbles them together and rearranges the words at random into a new assembly. This new poem, he says, will be “like you”. Beginning with the personal notebook instead of the public newspaper inverts Tzara’s idea. It makes your lines more “like the world”. To me, it seems to demonstrate how fundamental narrative is to our sense of being in the world.

JM: Yes! There is so much input that we navigate in our world every day, and the way we construct meaning and narrative allows us to make sense of our experiences. I wanted to play with the idea of how we can find the poetry amongst the mess of information we receive, and how to make a poem that feels like being in the world. I think there is a very human drive to try to make meaning from our experiences, and Infinite Iterative Piece invites audiences into a space that plays with how even the random can feel insightful.

NK: I’d be curious to know your thoughts on this creative process of randomisation and chance. Is this a new approach to language for you? How does it feel to ‘let go’ of your words and pass them over to a machine’s randomising technology?

JM: It has been really thrilling to see what the technology brings together, and a liberating release of control. Like most poets, I’m very curious about form and function, which spills over into my interest in video. My thinking was how to make the digital nature of this work enhance the words, which led to looking into randomising technologies. The work is also designed to grow and change over time, with more phrases and footage to be fed in—an infinite work in multiple directions.

NK: Writers like William S Burroughs used the Dadaist cut-up technique to look for implicit meaning in their writing. Did you have any kind of intention or hypothesis entering this work, or was it more of an open experiment?

JM: A lot of the work I have made previously for arts institutions has been based on a deep research period about the institution and the concepts of the show, which is the place the work is drawn from. I wanted to invert that approach for Between Waves and consider something that self generates, or creates meaning from atypical inputs. In that way it was an experiment in form while operating within the belief that poetry reveals our world back to us.

NK: That reminds me of the exhibition curatorial statement about “material and immaterial realms of knowledge and knowing”. What did this artwork teach you along these lines?

JM: This work plays with the tension of what we do at the edges of knowing. How do we make meaning in a world that is so overloaded with information that demands our attention constantly. It is both a way of relaxing into an immersive space for a period of time, while also providing audiences, including myself, moments of wisdom, absurdism, nonsense, and humour. In a world so full of horror, it is lovely to create a space of rest, reflection and poetry to calm the mind for a moment.

NK: I’ll look forward to being a part of the audience alongside you, Jazz. Thanks for your time.

Between Waves

Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre

(Sydney NSW)

27 July—29 September

This article was originally published in the May/June 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.