Tenderness, affection, gentleness. Common will, common heart, born from revolution. Intimate feeling, structures and systems. Potential for care, potential for violence. Interior, exterior, soft, hard. Genderless, genderless, adoption of definition, reclamation.

Tender Comrade, 柔情 rouqing 同志 tongzhi.

Quoting philosopher Michel Foucault’s 1981 article Friendship as a Way of Life, the exhibition text for White Rabbit Gallery’s current show Tender Comrade notes that “Everything that can be troubling in affection, tenderness, friendship, fidelity, camaraderie and companionship” connects the artists within it.

Indeed, Tender Comrade contains a spectrum of relation and troublings, but the first that stands out to me is not within a work but in the title of the show. ‘Tender’ and ‘comrade’ invite us to reflect on how we make and privilege meaning and draw on its potential. This is a matter Hongwei Bao puts forth in his 2018 book Queer Comrades: Gay Identity and Tongzhi Activism in Postsocialist China. Acknowledging tongzhi’s roots in unifying people in socialist China and the semantics of it referring to both ‘comrade’ and ‘queer’ in contemporary contexts, he argues for the “subversive potential” of this dual meaning.

As the show’s title brings the words ‘tender’ and ‘comrade’ together, how too, may we utilise this intricate relation to shape our understanding of the art it presents?

Since viewing Tender Comrade multiple times, I have also become intrigued by how the architecture of the gallery and exhibition design has lent itself to a storying of queer truth and resilience grounded in kin-aesthetics. Kin-aesthetics, as Tyler Bradway and Elizabeth Freeman advocate for in their 2023 book Queer Kinship: Race, Belonging, Form, is a core methodology of queer kinship theory that is concerned with “processes of figuration” that dismantle and reform the “categories and genres by which we understand relationships”.

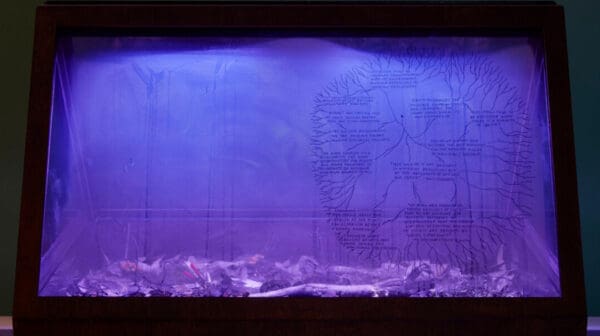

Within Tender Comrade, I have been most captivated by how the use of partitions, scale, and texture in modes of display have encouraged this. When you enter the show, floor-to-ceiling panels keep works on the ground floor hidden except for a fraction of Xia Han’s inflatable sculpture Humiliation (2022-2023) through what Xia describes as a rat hole. Through this and alternative entries created by the gallery, Shang Liang’s Boxing Man No.4 (2019), installed close to the ceiling leads audiences into an expanded viewing of the work.

These ways of experiencing Tender Comrade continue to extend into other floors of the gallery, such as through white curtains and coloured floors that are used to support the presentation of Sin Wai Kin and Lin Zhi Peng (No.223)s’ works, bringing in a softness that contrasts with the typical white walls and flooring. Invisibility, censorship, and the relational troublings that Tender Comrade aims to speak on are empowered by these physical provocations, and kin-aesthetics, which exists as the melding of kin, kinetics and aesthetics, comes to the fore.

Significantly, I felt that Isaac Chong Wai’s large-scale video installation and performance Falling Reversely (2021-24) that is presented on the highest floor of the gallery strengthened this, as movement of bodies on the screen in addition to movement that is required to experience the work, evoked emotional movement within. Working with performers of Asian descent in response to anti-Asian racism and violence, the video work, which plays out across seven screens that are installed across the floor depict the performers either falling individually or in a group, but in reverse.

The screens gently flash on and off in a choreographed irregularity, and sounds playing in reverse accompanies this experience. Reading the wall text about Chong’s lived experience with racism, I think not only about my own experiences with racism, homophobia or transphobia, but our fellow comrades’. The lives that have been lost, how hard it can be to find our feet again, the courage it takes to stand, let alone breathe movement through our bodies to dance through the rumblings of possible pushes to falling.

Chong’s earnest telling of shared experiences of marginalisation warms me, yet chills run down my spine, and I am reminded that this gentle collision and discordance is what Tender Comrade is about.

Through dissolved boundaries we reclaim our bodies and meet as kin, through openness to feeling we come together, arms locked.

Tender Comrade

White Rabbit Gallery

18 June – 19 November