Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

War and cultural destruction are echoed in art amid this deeply conflicted geopolitical moment. In Standing by the Ruins, a floor-based installation by Jeddah-born and based artist Dana Awartani at the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane, geometry and craft combine with the Arabic trope of “ruin poetry”. Today, the form, founded in pre-Islamic times, offers the inspiration of rebirth in the rubble.

Awartani, 37, who is of Palestinian, Saudi, Jordanian and Syrian descent, is creating a floor to be contemplated rather than walked upon; jewel-like with a subtle earth-coloured palette, and the repeating patterns that are found in mosques. Reflecting on recent crises in the Middle East, Chris Saines, director of the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), says the installation “talks about a sense of healing and reconciliation from the damage and the harm done by conflicts to the ordinary people who live through them”.

Awartani “works with artisans making these adobe dwellings with this long history in that part of Arab world”, adds Tarun Nagesh, curatorial manager of Asian and Pacific Art, citing Awartani’s installation as emblematic of this triennial’s emphasis on cultural knowledges that have been subject to devastation over decades and centuries. It will be the first time Saudi Arabia will be represented at the Triennial, which aims to make lost cultural heritage accessible again.

From November, the Asia Pacific Triennial, which was established in 1993, will present some 500 artworks from 70 artists across 30 countries for its 11th iteration. About 50 to 60 per cent the artworks are usually acquired by QAGOMA. “What really differentiates this project from others like it, is we travel and do in-country research, several times [in] each of the countries involved,” says Saines.

He says the Asia-Pacific curatorial team, working with the Australian and other curatorial teams, must deal with “tricky” logistics, working for instance, in Nepal, with the collective TAMBA and its video, woodcut prints, textiles, installation, music, photography and poetry. It’s one of four projects co-curated with arts professionals and community on the ground.

“We’ve been to Mongolia several times [but] we’ve only been to Uzbekistan for the first time this time—it just simply doesn’t have a cultural infrastructure, so obviously getting work out of that country is logistically very complex,” says Saines. Challenges include getting artworks out by small boat to be transferred to big vessels or planes, or Australian customs restrictions on materials that can be brought into the country.

Paired with the Saudi work will be an enormous weaving made of freshwater reeds from the Tongan island group of Vava’u, led by artist ‘Aunofo Havea Funaki and the Lepamahanga Women’s Group. Nagesh says the work is an “extraordinary 15-metre-long woven mat that this huge group of women have created, incorporating various motifs and patterns, and it nicely encapsulates one of the themes in the forthcoming triennial—the care relationships with the environment, for they are custodians also taking care of this fresh body of water”.

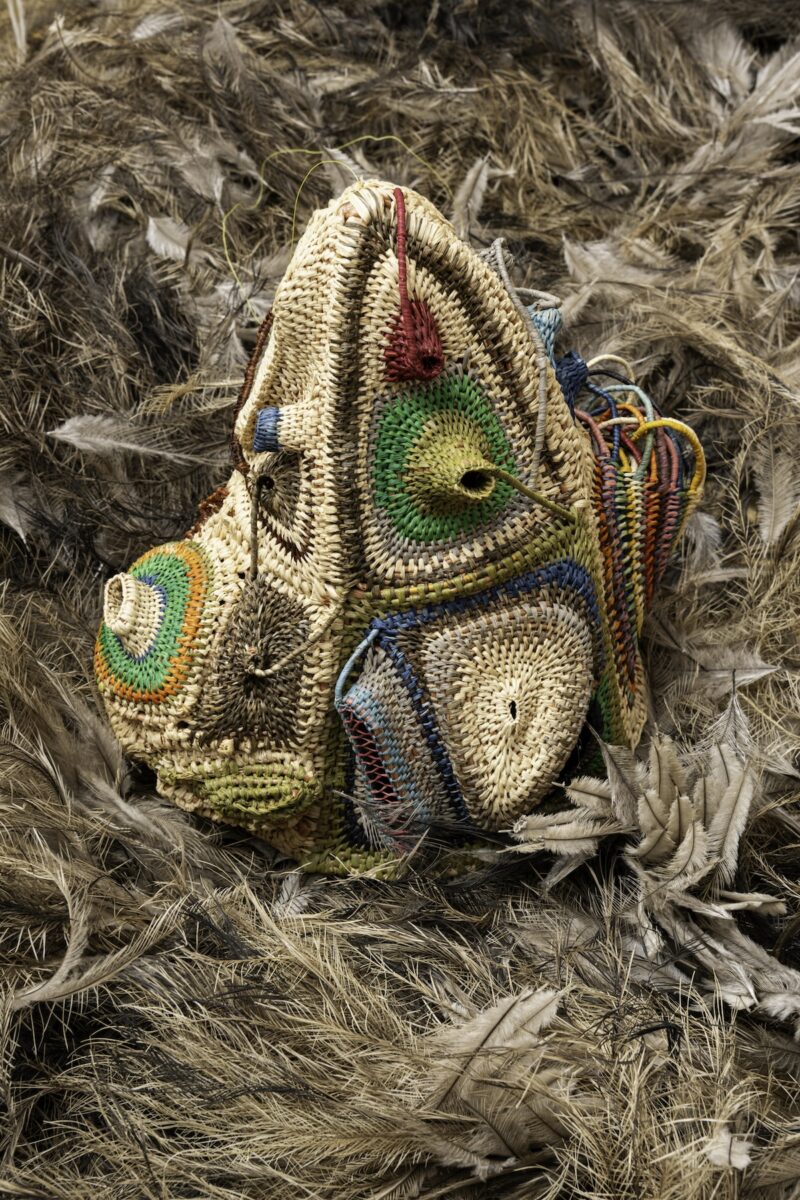

Such collectives are often located in remote regions, taking their time to yield material projects. In the case of the Haus Yuriyal collective of artists from the Papua New Guinea highlands, there is a notable diasporic approach, led by Brisbane-based artist Yuriyal Eric Bridgeman. Some of the collective live in live in the Jiwaka and Simbu provinces while others are based in Australia. In QAGOMA’s sculpture yard, they will exhibit paintings of fighting shields, carved tree fern sculptures and a video picture house in which films will be shown. They have also planted a harvest garden.

New commissions abound. Thai artist Mit Jai Inn, for instance, is building a maze-like installation in the institution’s water mall, with tunnels, curtains and scrolls, a little like the torqued steel ellipses of the late American artist Richard Serra but in “pure colour”, says Saines. For Nagesh, meanwhile, the triennial acknowledges that contemporary art thrives in multiple ways throughout our region and [strives] to create “a show not relying on American, Eurocentric understanding or approaches”.

One substantial body of work that is not a new commission is Māori artist Brett Graham’s Tai Moana Tai Tangata, which will occupy the full length of GOMA’s long gallery.

Graham’s Cease Tide of Wrong-Doing from 2020, a ten-metre high tower made of Kauri tree and metal, testifies to the relationship between Taranaki and Tainui Māori, centred around New Plymouth on New Zealand’s North Island. It also highlights their involvement in the Māori wars, fought with British troops.

On display will be a dray cart, a type of horse-drawn wagon, that Graham has recreated (and which QAGOMA has acquired). It was used by Māori to take food out to British surveyors, offering sustenance to strangers whose presence would only bring them harm.

“It was like a Mahatma Gandhi gesture,” says Saines, “and, to me, one of the most moving works in the show.”

11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

On now—27 April 2025

This article was originally published in the November/December print issue of Art Guide Australia.